Posts Tagged ‘English PEN’

Ten years ago, the particular context in which the British government chose to make April Fools of its citizens was the war in Iraq. This year, Iraq would seem a very exotic focal point for our denigration when the current government is so busy reducing our domestic certainties – a health service, a welfare state, a justice system – to the status of a blooper reel among the Extras on Michael Gove’s History of Great Britain DVD. When we’re losing track of who we are, of why we even exist as social animals, it is a challenge to contemplate the experience of Iraqis, by whom reality has, during these ten years, been viewed in a perpetual nightmarish REM. Yet Hassan Blasim‘s second collection for Comma Press speaks to our own, particularlised sensations of powerlessness, as much as to the self-evident contexts of war, exile and the way these narratives of suffering become absorbed into a nation’s culture and myths.

Ten years ago, the particular context in which the British government chose to make April Fools of its citizens was the war in Iraq. This year, Iraq would seem a very exotic focal point for our denigration when the current government is so busy reducing our domestic certainties – a health service, a welfare state, a justice system – to the status of a blooper reel among the Extras on Michael Gove’s History of Great Britain DVD. When we’re losing track of who we are, of why we even exist as social animals, it is a challenge to contemplate the experience of Iraqis, by whom reality has, during these ten years, been viewed in a perpetual nightmarish REM. Yet Hassan Blasim‘s second collection for Comma Press speaks to our own, particularlised sensations of powerlessness, as much as to the self-evident contexts of war, exile and the way these narratives of suffering become absorbed into a nation’s culture and myths.

A simple summary of The Iraqi Christ: this is the most urgent writing you will read in short fiction or any other literary format this year. To read these stories is to immerse yourself in tragedy and horror. The imprint of real lives – Blasim’s and those he has encountered – is as evident on the printed page here as lipstick traces on a cigarette, exacerbating the sense of grief that accompanies each story. Blasim’s debut collection for Comma, 2009’s The Madman Of Freedom Square (from which “The Reality and the Record” provided a previous post for this site), was an eloquent, retching cry of disgust; The Iraqi Christ seems to be steeped more in sorrow. And the incredible part is that, from this unimaginable sorrow, what emerges is a savage, unbearable beauty.

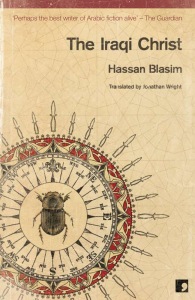

The stories portray characters locked in states of fretful, at times lurid, sensory dissonance. If you knew nothing of this book or Blasim’s literary antecedents other than David Eckersall’s cover design, pictured above, you might guess that Franz Kafka sits somewhere in the frame of reference. Short fiction routinely converses with its ghosts and Kafka’s presence is almost that of a recurring character, most conspicuously in The Dung Beetle, an overt reference to Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, with the concerns of the changeling Gregor Samsa, conceived during the First World War, transposed onto those of an Iraqi now residing in Finland, inside a ball of dung. In relating his fictional counterpoint’s story, Blasim makes what I take to be a more direct authorial interjection:

A young Finnish novelist once asked me, with a look of genuine curiosity, ‘How did you read Kafka? Did you read him in Arabic? How could you discover Kafka that way?’ I felt as if I were a suspect in a crime and the Finnish novelist was the detective, and that Kafka was a Western treasure that Ali Baba, the Iraqi, had stolen. In the same way, I might have asked, ‘Did you read Kafka in Finnish?’

Such is the sense of dislocation and depersonalisation, of inurement to brutality and reduction to absurdity, reading Kafka seems less of a choice or privilege than a routine motor function. The Dung Beetle quotes in full Kafka’s Little Fable in which a mouse articulates the essential condition of the Kafkaesque protagonist:

The mouse said, ‘Alas, the world gets smaller every day. It used to be so big that I was frightened. I would run and run, and I was pleased when I finally saw the walls appear on the horizon in every direction, but these long walls run fast to meet each other, and here I am at the end of the room, and in front of me I can see a trap that I must run into.,

‘You only have to change direction,’ said the cat, and tore the mouse up.

The earlier Ali Baba reference directs us to Blasim’s coupling of Kafka with Sheherazade and the One Thousand and One Nights tales, for which the narrative of the young bride using her powers of storytelling to stave off the daily threat of execution is the framing device, an appropriate analogy when claiming asylum.  The deadpan depravity in The Hole exemplifies how these strands become twisted together. The narrator, on the run from masked gunmen as chaos greets the collapse of the government, falls into a hole and encounters a “decrepit old man”, claiming to be a djinni (genie) and calmly carving chunks of flesh to eat from the corpse of a soldier who has previously fallen down the hole. There is no escape and the company only emphasises how divorced this place is from the reality the narrator has known.

The deadpan depravity in The Hole exemplifies how these strands become twisted together. The narrator, on the run from masked gunmen as chaos greets the collapse of the government, falls into a hole and encounters a “decrepit old man”, claiming to be a djinni (genie) and calmly carving chunks of flesh to eat from the corpse of a soldier who has previously fallen down the hole. There is no escape and the company only emphasises how divorced this place is from the reality the narrator has known.

In the 1001 Nights tale of Sinbad’s fourth voyage – several years into his latest enforced sojourn in a land in which he has initially been made to feel welcome and has become happily married – he learns of the bizarre local custom that, when a married man or woman dies, the living spouse is also thrown into the huge pit, that serves as a mass grave, accompanied by the humane provision of a spartan packed lunch for pre-death nourishment. Sinbad’s wife falls ill and dies and, sure enough, both her body and the breathing, protesting form of Sinbad are thrown in the pit. Sinbad survives in his pit of corpses by clubbing any newly-widowed arrival to death with a leg-bone and taking their bread and water for sustenance. These echoes cement Blasim’s storytelling within the traditions of the region but the stories that fuel his writing are timeless and universal, relating to the stark choices facing humans when everything that betokens their humanity has been stripped away. Italo Calvino is another writer cited, via his Mr Palomar character, who painstakingly seeks to quantify the contents of a disparate universe; when ‘Hassan Blasim’ appears as a character, shifting the boundaries of reality in Why Don’t You Write A Novel Instead Of Talking About All These Characters?, there are shades of Paul Auster’s introspections about the nature of truth and story. Where – in, for example, the meta-gumshoe story City Of Glass, itself Edgar Allen Poe’s The Man Of The Crowd by way of, yes, Kafka – Auster will use a character called ‘Paul Auster’ to interrogate the identity of the “I” in whose Point of View the story is being told, it’s couched within the ‘what-if?’ framework we might expect to find in any fictional narrative. Blasim operates from a starting-point in which life has already become that fiction. This is an object lesson for those who assume that it would be enough to transcribe and dust-jacket the extraordinary circumstances of their own lives in order to produce a compelling narrative. Blasim’s life enters Blasim’s fiction as a kind of exorcism: you don’t want to explore how much is actually a record of the truth because you can’t bear to look. In Why Don’t You Write A Novel…?, the narrator makes a prison visit to the man with whom he made the journey to escape Iraq and claim asylum in Europe. Along the way, this companion, Adel Salim, inexplicably murdered a drowning man whom they had met on the refugee trail:

‘Okay, I don’t understand, Adel,’ I said. ‘What were you thinking? Why did you strangle him? What I’m saying may be mad, but why didn’t you let him drown by himself?’

After a short while, he answered hatefully from behind the bars. ‘You’re an arsehole and a fraud. Your name’s Hassan Blasim and you claim to be Salem Hussein. You come here and lecture me. Go fuck yourself, you prick.’

The narrator, aware only of his work as a translator working in the reception centre for asylum seekers, retreats in confusion and struggles to recover memories from before his border crossing. In an encounter on a train, a man, carrying a mouse, identifies him as the author of several stories, including some of those contained in this collection. I don’t know whether Blasim was setting out to articulate this but there’s a particular bleakness to the writing life when you feel you’re holding the weight of all the blood and bones in the world but the only place you have to set it down is something so light and flimsy as the page of a book.

For all the postmodernism and the literary conversations, and the insect and, for Dear Beto, canine narrators, we are taken goosebump-close to what happens in everyday human lives in a protracted war situation, with Jonathan Wright’s translations ensuring no walls remain between these characters and the reader. The Iraqi Christ is eye-catchingly provocative as a title for the book but the story bearing that name provides a more straightforward explanation: it’s a reference to Daniel, an Iraqi soldier who’s a practising Christian and committed gum-chewer so known to his fellow soldiers as the Chewgum Christ, Christ for short. The story, though, we come to realise, is a kind of gospel told by a beyond-the-grave narrator who relates the miraculous, almost unconscious prescience with which this Iraqi Christ manages to evade death, to the point that he takes on a talismanic role among his comrades. A life avoiding death isn’t quite the same as a life, though, and there is sacrifice and redemption to follow in an ending that is built on tragic irony but has a strangely uplifting choreography to it.

For all the postmodernism and the literary conversations, and the insect and, for Dear Beto, canine narrators, we are taken goosebump-close to what happens in everyday human lives in a protracted war situation, with Jonathan Wright’s translations ensuring no walls remain between these characters and the reader. The Iraqi Christ is eye-catchingly provocative as a title for the book but the story bearing that name provides a more straightforward explanation: it’s a reference to Daniel, an Iraqi soldier who’s a practising Christian and committed gum-chewer so known to his fellow soldiers as the Chewgum Christ, Christ for short. The story, though, we come to realise, is a kind of gospel told by a beyond-the-grave narrator who relates the miraculous, almost unconscious prescience with which this Iraqi Christ manages to evade death, to the point that he takes on a talismanic role among his comrades. A life avoiding death isn’t quite the same as a life, though, and there is sacrifice and redemption to follow in an ending that is built on tragic irony but has a strangely uplifting choreography to it.

Further evidence of unexpected uplift comes in the final story, A Thousand and One Knives, a magic realist story of a team of street magicians whose ability to make knives disappear into thin air and then bring them back operates as a twin process of exorcism (again) and healing. The team have found one another through their gifts and rub along as a dysfunctional family group. In an attempt to understand what the trick of disappearing and reappearing knives might mean, the narrator is charged with researching the subject:

It was religious books that I first examined to find references to the trick. Most of the houses in our sector and around had a handful of books and other publications, primarily the Quran, the sayings of the Prophet, stories about Heaven and Hell, and texts about prophets and infidels. It’s true I found many references to knives in these books but they struck me as just laughable. They only had knives for jihad, for treachery, for torture and terror. Swords and blood. Symbols of desert battles and the battles of the future. Victory banners stamped with the name of God, and knives of war.

In the face of this understanding of knives, the group use their skills very little for show and not at all for profit but as a compulsion, like the stories of Sheherazade, because there are things that need to happen, because not doing it is too horrific to contemplate. When we learn of the baby born to the narrator and Souad, the only woman in the group and the only one able to make knives reappear, we see that they have cut themselves into one another’s flesh as well, in acts of transformative love and friendship that – remarkably, by the end of this remarkable collection – allow the reader to emerge with hope still intact, battered, but somehow reinforced.

The Iraqi Christ by Hassan Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright, supported by the English PEN Writers In Translation programme, is published by Comma Press and available in book and e-book form.