Posts Tagged ‘publications’

The Agonies and Alleyways

Posted on: November 13, 2014

My next blog was meant to be a taster for the new Comma Press science-into-fiction anthology, Beta-Life: Stories From An A – Life Future, to which I contributed The Longhand Option, a family tale of robots and writing in the year 2070 that involved fantastic support from my ‘science partner’, Francesco Mondada, and my editor Ra Page. In my story, Rosa, a writer, describes a finished story as being the

one that didn’t get to kill me.

Early on November 5th, years, days, months, hours, weeks of ignored, tolerated, undetected, late diagnosed, late presented, lifestyle-churned hernia and asthma problems nearly did kill me. They still could.

It’s 11.15pm, Wednesday 12 November 2014, and I’m writing with a pen and paper my shift nurse in the Royal Liverpool Hospital Intensive Care Unit, Alfie, brought me after changing my bed when I pissed it while listening to Sonny Rollins. I have a tube up my nose and down my through my gullet that’s draining stomach bile from my chest and lungs. I’m hooked up to drains, monitors and nebulisers.

In truth, my life has never held such dignity.

I am writing this as a result. This is the story to bring me back to life.

If you are a friend or colleague or acquaintance of mine who has noticed this and it’s the first time you knew I was ill, please accept apologise for the poor planning. And please keep checking this blog for further news so my wonderful girlfriend is able to stay on top of all she’s been left alone to deal with.

If you would like to help, keep reading, reposting, looking out for each other. I’m posting this just before 5pm on Thursday 14th. Ian gave me a shave this morning and Sara just washed my hair. So I am OK and ready to tell more – about the Agonies and Alleyways and the dignity that I am being given to lead the way back to a better life than before.

Review: “Moss Witch and other stories” Sara Maitland (Comma Press, 2013)

Posted on: October 16, 2014

Not simply because it’s been a miserably long time since I last posted here but because of the subject to hand, talking about Sara Maitland’s fusions of science and fiction is truly a long-overdue pleasure. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book of short stories that came across as such a joy to have written. To be frank, the writerly envy Moss Witch and other stories inspires is enough to play merry hell with your entire molecular structure. Having said that, you read a story like A Geological History of Feminism, and you’re very glad that the writer who got to have all this joy was one who can extract from the material a passage of prose as lithe, accomplished and thrillingly quixotic as this:

Not simply because it’s been a miserably long time since I last posted here but because of the subject to hand, talking about Sara Maitland’s fusions of science and fiction is truly a long-overdue pleasure. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book of short stories that came across as such a joy to have written. To be frank, the writerly envy Moss Witch and other stories inspires is enough to play merry hell with your entire molecular structure. Having said that, you read a story like A Geological History of Feminism, and you’re very glad that the writer who got to have all this joy was one who can extract from the material a passage of prose as lithe, accomplished and thrillingly quixotic as this:

And one dawn, so bright that the rising run pushed a shadow-Elsie through the waves and the solid, real Elsie seemed to be chasing it, she had felt a deep surge of energy, more powerful and precise than she had ever felt before. It pushed her up and forward, making her want to sing, to cry out for the beauty and freshness and loveliness of the future. Later, peering down over the charts on the cabin table, she knew what it was. She was sailing over the mid-Atlantic ridge and deep, deep below her, through first blue, then green and down into black water, down below where no one had ever been or could ever go, there was new liquid rock welling up, pouring out, exploding into the cold dark, and crawling east and west either side of the ridge, forming a new, thin dynamic crust, pushing the Americas away from Africa and Europe, changing everything, changing the world. A plate boundary where new rocks are born out of the cauldron below.

This is audacious stuff: the story has Ann, the sole crew member of ‘Elsie’, recounting this journey many years later to her niece Tish, to illuminate how deeply entrenched were the struggles undertaken by the early feminists and to illustrate the resolve they needed to bring about the ground-breaking changes taken for granted today. The image of tectonic plates clashing, oceans breaking and continents shifting is more than a metaphor, though – it’s the real thing, and our involvement in story and character is met in equal measure by a head-spinning tutorial in scientific theory.

Each of Maitland’s stories has come about in consultation with an appropriate scientific expert, ranging across the scientific disciplines to include Earth Scientist Dr Linda Kirstein, consultant for the story quoted above, as well as an ornithologist, an astrophysicist, a mathematician, a stem cell researcher, one of the particle physicists at CERN, and the University of Surrey’s professor of theoretical physics, Jim al-Kalili, who’s famous enough to get to pose for photographs in which he ruminates towards the sunset like he’s a bowl cut short of a Brian Cox. How these dialogues have fed into Maitland’s process is explained in part by an afterword, accompanying each story, by the relevant consultant. So Dr Tara Shears from CERN explains Dirac’s equation – “a simple, far-reaching collection of symbols that led to the prediction of anti-matter” – which is the basis for Maitland’s troubled twins parable, The Beautiful Equation.

Each of Maitland’s stories has come about in consultation with an appropriate scientific expert, ranging across the scientific disciplines to include Earth Scientist Dr Linda Kirstein, consultant for the story quoted above, as well as an ornithologist, an astrophysicist, a mathematician, a stem cell researcher, one of the particle physicists at CERN, and the University of Surrey’s professor of theoretical physics, Jim al-Kalili, who’s famous enough to get to pose for photographs in which he ruminates towards the sunset like he’s a bowl cut short of a Brian Cox. How these dialogues have fed into Maitland’s process is explained in part by an afterword, accompanying each story, by the relevant consultant. So Dr Tara Shears from CERN explains Dirac’s equation – “a simple, far-reaching collection of symbols that led to the prediction of anti-matter” – which is the basis for Maitland’s troubled twins parable, The Beautiful Equation.![]()

In her acknowledgements, Maitland thanks the scientists and muses, “I wish I believed they had as much fun as I did.” It’s easy to characterise the relationship between a writer and a scientist in this sort of collaboration – and it’s one I’ve experienced, with Liverpool University’s Professor of Evolutionary Biology, Greg Hurst and very recently with the robotics pioneer, Francesco Mondada – as resembling that between an adult and a very clever child. Most of the child’s questions are easy enough to answer, but you’re delighted at her fascination with the subject – and every now and then, she’ll come up with a fresh insight that goes beyond the limits of the workaday. It might leave the scientist with a warm glow and a pocketful of inspiration – during our work together on the 2009 Evolving Words project, Greg wrote more poems than anyone else – but the impact on the writer is seismic. If I experienced that within either one of my scientific contexts, imagine something similar but fourteen times over and you get a sense of the excitement surging through Maitland’s writing.

The spectrum of scientific disciplines commandeered for Moss Witch is matched by Maitland’s range of storytelling textures. There are trace elements of Jorge Luis Borges in the willingness to converse with the prehistory of the modern short story. Though there are no explicit pastiches, we brush up against Biblical legend, Greek mythology, Gothic dysmorphia – in the beguiling Double Vision, which had previously surfaced in Comma’s The New Uncanny – and the pitch-dark charm of the title story’s eponymous candidate for a belated place in the Grimm fairy tale canon, where we might expect her to beat the crap out of any bold young princes who dare to come riding by:

The evening came and with it the chill of March air. Venus hung low in the sky, following the sun down behind the hill, and the high white stars came out one by one, visible through the tree branches. She worked all through the darkness. First, she dehydrated the body by stuffing all his orifices with dry sphagnum, more biodegradable than J-cloth and more native than sponge, of which, like all Moss Witches, she kept a regular supply for domestic purposes. It sucked up his body fluids through mouth and ears and anus. She thought too its antiseptic quality might protect her mosses from his contamination after she was gone.

Rumpelstiltskin, we can note, was a rank amateur.

This is as much about the discoverers as the discoveries and another storytelling element is the speculative biography, similar to the approach used by Zoe Lambert for several stories in her The War Tour collection. One example of a story containing a scoop or two from a real life is the heartbreaking – but so beautiful it manages to be uplifting as well – The Mathematics of Magic Carpets, about the ninth century inventor of algebra, Abū‘Abdallāh Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī. Maitland’s writing, whether veering towards myth or folklore, biography or contemporary (and indeed future-facing) short fiction, has the ability to charm and cheer even when there is a dark or sorrowful human story to be told. Science is so often the villain in fiction or at best the well-meaning catalyst for a disastrous future (see the James Franco character in the 2011 film Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes as an example of the latter) but Sara Maitland’s collection speaks with a stirring optimism that has been a major influence on my own recent experiments blending science and short fiction. My consultation with Francesco Mondada has produced The Longhand Option, one of the stories in Comma’s Beta-Life: Stories From An A-life Future, launching shortly in Lancaster and Manchester – more details should appear very soon on this blog.

The Hate Inside The Inkwell

Posted on: April 10, 2013

A couple of weeks ago, I joined in a discussion with fellow posters on The ‘Spill music blog on the issue of developing a fondness for music your partisan allegiances may once have instructed you to disdain. While citing my enduring contempt for Spandau Ballet’s True, I recognised that some affection has grown atop my identification of its vices, that I indeed now love the song for having been there for me to hate for so long. Even its specific offences – the overwrought, meaningless meaningfulness of lyrics like I bought a ticket to the world/ But now I’ve come back again – seem pardonable teenage misdemeanours with three decades of music listening as hindsight.

Precisely how I feel about an old pop song is neither here nor there, but it got me thinking about malignant creative influences. When asked to cite the influences that helped shape the writers, artists or even just the adults we have become, it’s natural to accentuate the positive. The writer I grew into certainly carried with him the early introductions to Shakespeare, Orwell and Harper Lee; the exposure via John Peel’s radio show to Linton Kwesi Johnson, John Cooper Clarke and Ivor Cutler, or via The Guardian and The Observer to James Cameron, John Arlott and Michael Frayn; the schoolboy aspirations to be Dickens, Fitzgerald, Conrad. But the transitions that occur throughout a life don’t happen as a victory parade; we also evolve by mutation, and among the many factors that shape us are our corrosive emnities.

I find little use for Hate these days, not proper hate, gut-knotting, blood-curdling; the thought-through hate; the uncut hate. There’s a quote from Joseph Conrad which reminds me of why he was one of my teenage literary heroes:

A writer without interest or sympathy for the foibles of his fellow man is not conceivable as a writer.

It’s a line I push to creative writing students now, the majority of whom were not alive in November 1990.

“And death…where is it?”

He sought his former accustomed fear of death and did not find it. “Where is it? What death?” There was no fear because there was no death.

In place of death there was light.

“So that’s what it is!” he suddenly exclaimed aloud. “What joy!”

Leo Tolstoy’s novella The Death Of Ivan Ilych encapsulates Conrad’s point. Ilych is not a likeable nor especially admirable man, and he is in possession of a considerable range of foibles. Tolstoy shies away from none of this in presenting Ilych’s life but, as the character slips towards death, our compassion is engaged. Beyond identifying with his struggle to comprehend what is killing him, and the despair in being forced to accept its irreversibility, we embrace Ilych fully in his final moments. When all the competing pressures are removed – around how to live, what to strive for, what greatness to achieve and what a signficant person to become – Ilych is able to free himself from the fear of death [above] and share with each of us the beautiful insignificance of our lives. And that really is the place to get to, since it’s where we’re all going.

Nobody this week has tried to make the case that Margaret Thatcher’s life was insignificant.

In my 2008 short story, A Different Sky, I wrote a scene set in November 1990 featuring some dancing in the street that may foreshadow some of April 2013’s transgressive street parties:

Max saw Will on the other side of Leece Street, by the hole-in-the-wall ‘Dog Burger’ bar, so he placed a clenched fist high in the air as a salute. Will crossed the road carefully, then skipped the rest of the way, pumping both his fists.

‘Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, YEESS!’ he yelled at Max.

‘Oh my God!’ Max shouted back, ‘I can’t believe it – finally!’

‘Eleven years, man – e-lev-en years.’

They stood and laughed in each other’s face. ‘I really can’t believe it,’ Max said again. Will ran on the spot. Max took Nelson out of the pram and raised him up towards the sky, like a scene from the adverts for Gillette.

Some might say that the day Thatcher left her office as Prime Minister was the right day for dancing, although it wasn’t us forcing her out but her erstwhile seemingly sycophantic Cabinet colleagues, and the Conservative government we opposed didn’t end for another six-and-a-half years. So that moment, in May 1997, might have been the right time to celebrate. Except tempering the euphoria was the awareness that the newly-elected Labour Party had become a very different being since Thatcher re-framed the national debate. Tony Blair’s goverment just had to show up to appear more socially progressive than John Major’s “Victorian family values” and Thatcherite policies like “Clause 28”, Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which sought to prohibit teaching and educational materials promoting the acceptability of homosexual relationships and which must seem to young people today like the basis for a Horrible Histories song. However, Blair styled himself as Thatcher’s political heir and New Labour’s economic and foreign policies remained true to her ideologies, while the retention of power underscored comparable authoritarianism. The salutations this week when an octagenerian dementia-sufferer died from a stroke, that we’d at least seen off the Devil of our age, can’t have gone unaccompanied by the understanding that, if Maggie Thatcher was ever a crusader against the welfare state, a symbol of social division and an enemy of the poor, then there’s a mob of millionaires who are very much alive, determinedly in charge, and bringing in divisive policies that exceed even her grandest follies. The time for dancing would have been when we’d defeated her politically, but our moment of victory never really came, and my 1990 revellers in A Different Sky unwittingly acknowledge this:

When [Nelson] came to rest on Dad’s shoulders, he could now see the top of another man’s head and there was hardly any hair there at all, just two grey patches at the sides. The man was walking past Dad and Will but he stopped for a moment, and his stiff grey suit made their denims seem even more soft and crumpled.

‘Great day, isn’t it, lads?’ the man said.

Will adjusted his voice to register his upbringing rather than his residence. ‘Absolutely, sir. Ding-dong, the witch is dead – now if we can just find a way to get rid of Bush and get out of the Gulf, we’ll be sorted.’

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Interviewed on the BBC website about his 2004 novel of the 1984-5 miners’ strike, GB84, David Peace commented on the impact of Thatcher’s confrontation with Arthus Scargill’s National Union of Mineworkers, whom she claimed represented “the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight [than the Argentinian “enemy without”, defeated in the Falklands War] and more dangerous to liberty.”:

It wasn’t the strike that changed lives and communities, it was the government policy and the forces they brought to bear upon pits and communities in order to close pits that changed lives. I think it’s hard for people in 2004, especially younger people, to understand the levels of sacrifice that people underwent in mining communities during 1984/85; the loss of, on average, 9000 pounds per miner, 11,000 arrested, 7000 injured, two men dead – that men and their families did this in order to defend not only their own jobs and communities, but also those of other men in other pits and communities. Those pits and communities are gone, organised labour is gone, socialism is gone and with it the heritage and culture that held people and places together. That government and their policies changed everybody’s lives, not only the ones that had the courage to at least stand and fight.

GB84 is a brilliant piece of writing and an exceptional work of multi-layered storytelling. Reading it was also one of the most unpleasant experiences I’ve had with any work of literature, so effective was it in pitching me right back into the moment of the miners’ strike, the high point of defiance against Thatcherism and the decisive factor, as Peace says, in bringing to an end the influence of organised labour in British political life. Hate was thick in the air supply then. In a suburban South London sixth form, nowhere near the war zones of what were still considered mining communities, I experienced feelings of solidarity and venomous hostility towards classmates based on their relative views on the strike. It was a daily consideration for over a year, the country felt like an emotional furnace, and it was nasty. Reading Peace’s novel, it was a shock to be reminded of how much hate had governed everyday life, but in the midst of the Thatcher years, the strike was just the most full-throated expression of the hate that muttered through the 80s.

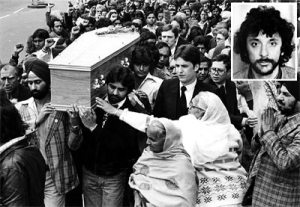

I don’t think it was Maggie Thatcher who taught me how to hate. For a non-white kid in a British city in the years after Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech, politicisation came early. The occasional insult in the street didn’t hurt much but it alerted me to racism, gave me – by way of the National Front – a focus for my nascent fear and loathing, and directed me (following my big brother’s tastes) to a mainly musical kindergarten for our political education. The Tom Robinson Band were stalwarts of the Rock Against Racism movement and were magisterially right-on, pushing anti-racism alongside feminism, unionism, opposition to police brutality and gay liberation. The anti-authoritarianism of Punk packaged hate in a discordant rage and cynicism that would have suited Thatcherism but related to the grey overture of the Wilson/Callaghan Labour years: entrenchment in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’, the strident pomp of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee and the Winter of Discontent, along with the rise of the NF. As formative to a clenched-fist political identity as The Clash were, though, nothing would give vague left-leaning beliefs such focus and purpose as Thatcher’s response to the death of Blair Peach.

In the weeks before the 1979 General Election, in which the National Front fielded over 300 candidates, the Party staged a campaign march through Southall, one of the areas of London most synonymous with immigrant settlement. Peach was a white New Zealander, working in London as a teacher, and part of the anti-racist counter-protest which clashed with riot police. Though it took 30 years for the Metropolitan Police to issue even this basic acceptance of claims made at the time, Peach was beaten to death with a blow to the head from a police officer. I was approaching 12 when this happened. I was not world weary. I had not seen it all. I was shocked and chilled that racism had got so bad that they were now killing white people to protect it. And then Mrs Thatcher, campaigning to be Prime Minister, offered her understanding of the situation:

“People rather fear being swamped by an alien culture.”

The man was dead and her compassion was for the racists who decided I didn’t belong in the only country I’d ever known. Ten days after Blair Peach’s head was caved in, Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister. She’d give me plenty of reasons to stoke that hatred over the years but it was there from Day One for me, and for millions of others who refuse to be hypocrites by joining in the steel toe-capped hagiography in progress, and the millions who promised themselves they’d live to see this day but didn’t make it. It’s political, but it’s always been personal.

I can testify that Thatcher was an immense influence on the reasons I had to write, on the things I chose to write about, on the decisions I made about what I wanted from my writing life and very likely the things I wouldn’t do in the interests of a writing career. But hating Maggie Thatcher isn’t a sustainable creative impulse. She did, though, make me take care to choose my words. So I won’t waste next Wednesday mourning her passing. If there’s a glass to be raised, I’ll raise it to Blair Peach.

It’s a curious business, when the content of a short story anthology is made up of stories in competition with one another. If you haven’t heard the BBC Radio 4 broadcasts of each of the ten shortlisted stories in the annual, BBC/Booktrust-sponsored, increasingly high profile and, for this Olympic year only, International Short Story Award, or if you’ve not yet caught up with the podcasts or got hold of the anthology, stewarded by Comma Press, featuring all ten finalists, you may now be curious as to why the Bulgarian writer, Miroslav Penkov was declared the winner of the £15000 prize. In one sense, the answer is simple to the point of idiocy: the judges got it right. Penkov’s story, East Of The West was the best of the bunch, and the runner-up, Henrietta Rose-Innes’ Sanctuary, was entirely deserving of that recognition. That’s easily declared, but the reasons why you might reach that conclusion, from reading the anthology, are a whole lot more complicated.

It’s a curious business, when the content of a short story anthology is made up of stories in competition with one another. If you haven’t heard the BBC Radio 4 broadcasts of each of the ten shortlisted stories in the annual, BBC/Booktrust-sponsored, increasingly high profile and, for this Olympic year only, International Short Story Award, or if you’ve not yet caught up with the podcasts or got hold of the anthology, stewarded by Comma Press, featuring all ten finalists, you may now be curious as to why the Bulgarian writer, Miroslav Penkov was declared the winner of the £15000 prize. In one sense, the answer is simple to the point of idiocy: the judges got it right. Penkov’s story, East Of The West was the best of the bunch, and the runner-up, Henrietta Rose-Innes’ Sanctuary, was entirely deserving of that recognition. That’s easily declared, but the reasons why you might reach that conclusion, from reading the anthology, are a whole lot more complicated.

To read an anthology compiled in these circumstances at this precise time is to seek to pick out a winner, but once the fifteen grand’s worth of kerfuffle has passed on by, the book remains a short story anthology. Even though no overlying thematic concern has guided the writing of the ten stories; even though, beyond what the selection says about the judges,

the programming of the stories as they appear in the anthology derived from no stronger editorial line than the alphabetical order of the writers’ surnames: still, the stories speak to each other, as in any other collection. Writerly concerns overlap and individual creative decisions coalesce by the accident of their mutual proximity into something that resembles a trend. Emotions, gathered in one place, spill out in another and it becomes hard to work out if the story in front of you can take sole credit for your response. Leave aside all this, and we still have the essential truth about short stories that the best grow in their absence: it’s not when we scrutinise them but in those sudden, private moments when we find that they are scrutinising us, that the power of an individual piece is felt. In such a context, picking a winner should be like punting on raindrops sliding down a windowpane: this one may win, or that one, but all that tells you is that it’s raining outside. There was little to guide us as to the outcome from the previous year’s winner, D.W. Wilson’s The Dead Roads, nor from 2010’s selection by, David Constantine, so it all comes down to the stories themselves. Read as a form guide, the anthology mocks the very process it belongs to, while, read as an anthology, it exceeds its reach.That there are stand-out stories shouldn’t deter anyone from investigating what is going on, thematically and within the writing, in the eight also-reads. Escape plays a persistent role in just about all the stories, the tone set by Lucy Caldwell’s opener, Escape Routes and reinforced by Julian Gough’s The iHole. Escape here – and in the closing story, A Lovely and Terrible Thing by Chris Womersley – is the objective itself, with a destination, or life beyond the moment of release, not a consideration. Caldwell’s Belfast story of the friendship between a young girl and her babysitter, whose ability to connect to the narrator through gaming contrasts with his wider sense of alienation. It articulates a world that’s very close to that of adults but utterly cut off from it as well. The references to gaming and youth depression suggest a nowness to Caldwell’s writing, but Gough’s lovely take on a post-CERN near-future, in which recycling is replaced by the mass production of personal, portable black holes, stands out more clearly as the shortlist’s outstanding depiction of the Way We Live Now. I felt Gough’s pursued the grand narrative arc of his satire too far, and the detail and comedy became too broad, in comparison with a recent Will Self story, iAnna, which makes the comment on technology and contemporary culture while remaining with the characters.

The three stories set in Australia each capture painful hours in the breaking up and holding together of families. M.J. Hyland has a tense father-son rapprochement in Even Pretty Eyes Commit Crimes. Carrie Tiffany depicts a child negotiating a path to a future with an absent father in Before He Left The Family. Womersley balances a supernatural tale, that might almost be lifted from an M.R. James treasury (and evokes Paul Auster’s Mr Vertigo), with a portrait of a father cut off from his family due to his daughter’s medical condition. Each manages to present a reality more convincing than is conveyed by Adam Ross, whose In The Basement uses the device of the extended dinner party anecdote rather more theatrically than I was comfortable with, though it’s equally the type of thing Truman Capote or, again, Auster might have done with the same yarn to spin.

Krys Lee’s The Goose Father has wonderful touches in the slow (but, even allowing for the form, perhaps not quite as slow as the situation demands) epiphany of an austere middle-aged man encountering an unstable but sprite-like young man. This South Korean narrative was the story that gathered me in the most, outside of the top two and the opening half of Gough’s The iHole. Deborah Levy, denied a league and cup double but now freed to concentrate on the Man Booker Prize, lets off the most fireworks in her prose for Black Vodka and, in her narrator, has a character who absolutely commands our attention. It’s adventurous, playful writing but ultimately it’s a sketch of a character that Levy might lend to aspects of future novels. It will also, incidentally, give you a raging thirst for flavoured vodkas.

In the alphabetical sequencing of the anthology, Rose-Innes follows Penkov and dramas viewed from across – and swimming in – rivers feature in both. It’s another example of the emotional chords that can be struck accidentally between stories which each have plenty of their own weight to carry. If there is an arc a reader goes through in reading a short story collection, there might be a science to my being especially receptive to these two stories. So, yes, judging is complex but the most instinctive personal responses have authority in this regard. There are stories that grab hold: Rose-Innes did this with Sanctuary, a family tragedy observed from a series of vantage-points, each one projecting a role onto the narrator of innocent bystander, unwitting voyeur, detective and eventually protector. The detail and intimacy with the land, in this case the South African veldt, has the kind of clarity we’d associate with John Steinbeck, and Rose-Innes would have been my winner had the decision been made on immediate completion of the task of reading all the stories.

In the alphabetical sequencing of the anthology, Rose-Innes follows Penkov and dramas viewed from across – and swimming in – rivers feature in both. It’s another example of the emotional chords that can be struck accidentally between stories which each have plenty of their own weight to carry. If there is an arc a reader goes through in reading a short story collection, there might be a science to my being especially receptive to these two stories. So, yes, judging is complex but the most instinctive personal responses have authority in this regard. There are stories that grab hold: Rose-Innes did this with Sanctuary, a family tragedy observed from a series of vantage-points, each one projecting a role onto the narrator of innocent bystander, unwitting voyeur, detective and eventually protector. The detail and intimacy with the land, in this case the South African veldt, has the kind of clarity we’d associate with John Steinbeck, and Rose-Innes would have been my winner had the decision been made on immediate completion of the task of reading all the stories.

What also happens with stories, though, is this: they won’t let you go. East Of The West hefts the history of a people, the Kosovan war, and twenty years of a love story into what still manages to be a concentrated, complete short story. I mentioned the breaking up and coming together of families in other stories but, here, those moments of crisis are the natural order for a family divided by the width of a river but, in that division, also split into two nations and between prosperity and struggle. Tragedy hovers, ill-defined at first but, over the years, it acquires names and accompanies the narrator, Nose, in his every footstep through adolescence and the plans he has for his adulthood. Penkov gives us a character whose emotions, in the extraordinary circumstances of his life and the history framing it, are utterly real. It’s a credit to the BBC’s award and the good fortune that the Olympic celebration made it eligible that this funny and moving short story will come to wider attention.

What also happens with stories, though, is this: they won’t let you go. East Of The West hefts the history of a people, the Kosovan war, and twenty years of a love story into what still manages to be a concentrated, complete short story. I mentioned the breaking up and coming together of families in other stories but, here, those moments of crisis are the natural order for a family divided by the width of a river but, in that division, also split into two nations and between prosperity and struggle. Tragedy hovers, ill-defined at first but, over the years, it acquires names and accompanies the narrator, Nose, in his every footstep through adolescence and the plans he has for his adulthood. Penkov gives us a character whose emotions, in the extraordinary circumstances of his life and the history framing it, are utterly real. It’s a credit to the BBC’s award and the good fortune that the Olympic celebration made it eligible that this funny and moving short story will come to wider attention.

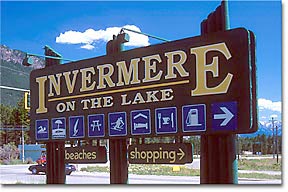

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

Each of the stories in Once You Break A Knuckle features a male protagonist, and Wilson very often examines them within their relationship with other men: fathers and sons, childhood friends, brothers, mentors, employers. Some characters recur at different moments in their lives while others unfold over years within the one story. An example of the latter is Winch, who emerges from the shadow, and initial narrative Point of View, of his father, Conner, in Valley Echo. The father here, as elsewhere in the story cycle, represents at various times – and often simultaneously – an aspirational role model and a booby trap to avoid. Conner and Winch have in common abandonment by Winch’s mother and, when the sixteen year-old Winch develops a crush on a teacher, Miss Hawk, he is disturbed to discover more common ground with his father. Miss Hawk’s presence in this story is typical of the way women feature throughout the collection.  Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

She wore track pants and a windbreaker, had probably been out running – one of those fitness women with legs like nautical rope.

Ray has returned to the area from what seems to have been a self-imposed exile following the breakdown of his relationship with Tracey, who left him for a rival building contractor. Now, with Mud and Alex in support, he begins to consider a new start and a possible relationship with a co-worker, Kelly. The reason for leaving and the reason for staying: the women are irrevocably linked to the emotions the men associate with the town itself.

The machinery of the town is wrought from masculinity. This is best exemplified in the person of John Crease, mounted policeman, security ‘consultant’ in post-war Kosovo, single father, martial artist, a man who, we learn in the opening story, The Elasticity of Bone:

[has] fists…named “Six Months in the Hospital” and “Instant Death”, and he referred to himself as the Kid of Granite, though the last was a bit of humour most people don’t quite get. He wore jeans and a sweatshirt with a picture of two bears in bandanas gnawing human bones. The caption read: Don’t Write Cheques Your Body Can’t Cash.

The description is courtesy of Will, John’s son. Their relationship is claustrophobic, the tenderness expressed in verbal and often physical sparring, and the impression grows across the various stories in which they appear that the bond is built on a stand-off between each man’s occult adherence to his own concept of male-ness. Although his father’s profession beckons, Will is, could be, might become a writer. It’s the time-honoured route out of the small town so much fiction and drama has taken, and which was so wonderfully lampooned by the Monty Python Working-class Playwright sketch (“Aye, ‘ampstead wasn’t good enough for you, was it? … you had to go poncing off to Barnsley, you and yer coal-mining friends.”). Wilson never targets the obvious dramatic flashpoint, never takes a Billy Elliot path by making Will’s writing a fetishised focal point – he just allows the slow resolution to roll into view. When this happens – as with other characters when we catch up with them after encountering their younger selves in earlier stories – the effect is slightly shocking but feels true. This may be because, while the where of these stories is unchanging, the when dances about, evading scrutiny of its larger contemporary narratives and instead presenting the community in moments of temporal suspension: what, in the title story, Will’s loyal friend Mitch describes as “days like these with Will and his dad, looking forward in time or something, just the bullshit of it.” It’s a pretty workable summary of what I mean by real time short stories, and certainly what is a particular trait of short fiction: presenting moments that may be lifted out of the specifics of time and space in their settings but that manage to illuminate something more elemental about the human condition.

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The town lies in the midst of open fields, but beyond the fields are pleasant patches of woodlands. In the wooded places are many little cloistered nooks, quiet places where lovers go to sit on Sunday afternoons.

– but where, in this story, Adventure, Anderson tells of a young woman, Alice, who does not join her contemporaries in the woods but instead –

As she stood looking out over the land something, perhaps the thought of never ceasing life as it expresses itself in the flow of the seasons, fixed her mind on the passing years.

Such is the inevitable fictional loop of the small town narrative, where characters are defined by place, and thereby defined by their bond to or desire to liberate themselves from the “never ceasing life” with its circular dramas and choreographed quirks.

The men in Invermere push and pull one another in various directions but, in the main, they seem scooped up from the same gravel. Difference relates to disorder in a context like this, as in Frode Grytten’s Sing Me To Sleep, where the alienation endured by the middle-aged Smiths fan mounts, through grief at his mother’s long illness and death, and his own quiff-kitemarked loneliness, to a beautiful, baleful crescendo of resolution. In Wilson’s The Mathematics of Friedrich Gauss, the first person narrative builds up a similar momentum, though the emotional surge at the end merely serves to clear away the narrator’s denial and reveal his truth to devastating effect.  Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

The day after we met, on that beach near Saskatoon, my wife showed me how to gather barnacles for protein. She shanked a pocket knife between the rock and the shell and popped the creature off like a coat snap, this grin on her face like nothing could be more fun. I never got the hang of it. She has stopped showing me how.

– We’re not unhappy, I tell my wife.

– Don’t you ever wonder if you could have done better? she says, and she looks at me with eyes grown wide and disappointed.Gauss’s first wife died in 1809, complications from childbirth. A number of people have recounted the scene on her deathbed – how he squandered her final moments, how he spent precious hours preoccupied with a new puzzle in number theory. These tales are all apocryphal. These are the tales of a lonely man. Picture them, Gauss, with his labourer’s shoulders juddering, Johanna in bed with her angel’s hair around her like a skimmer dress, his cheek on the bedside, snub nose grazing her ribs.

It’s one thing to write about the business of being a man with prose that strides into the room, waves its Jeremy Clarkson arse in your face by way of manly humour, and makes a Charlton Heston grab for Chekhov’s gun, placing it in the grip of its cold, dead narrative – but a writer who understands men will be able to depict emotion the way Wilson does in the passage above, and throughout Once You Break A Knuckle. There are versions of being a man here so alien to my sensibilities, Bruce Parry‘s inductions into shamanism in Borneo seem, in comparision, as complicated as setting up a Twitter account. Yet the alchemy at work in D.W. Wilson’s writing is such that, when I think about each of the characters in each of the stories, I can’t help feeling that I have been, at some point in life, some small part of every one of them.

D.W. Wilson‘s Once You Break A Knuckle is published by Bloomsbury Press.

What Do You Want To Know?

Posted on: March 19, 2012

I know little about cars. Until I learned to drive in my mid-30s, I knew even less than that.

This week, my lack of knowledge proved costly and, while it’s safe to say that the little I knew about cars has now increased, I regret that the lesson was so expensive. That I should know more about cars seems a self-evident truth but there was something, too, to be taken from all the not knowing. The absence from my life of a raging need ever to sit down to watch Top Gear strikes me as a richness, as does the knowledge that no advert for a car costing half the price of a decent two-up, two-down terrace is ever likely to engorge my glands with desire. As a motorist, I’m also a person; there’s a balance to be found. As a writer of fiction, though, I’m always saving a seat within my consciousness for a character yet to emerge: if one arrives who happens to be a petrolhead, that’ll be another occasion when it’ll occur to me that I ought to know more about cars.

I have a modest facility with languages but one of the many languages I don’t know at all is Croatian. This has rarely seemed a major gap: I may harbour thoughts of holding down a conversation with the Tottenham Hotspur midfielder Luka Modric but I suspect that my contribution would be a babble of incoherent fanspeak, irrespective of the nominal lanaguage. From this week, though, my lack of Croatian will be a source of some bother due to the publication of three separate Croatian translations of my 2008 story, Scent. The translations appear, respectively, in Pandemonij, Okreni na priču and Tko tu koga? – as well as in pdf format online here – published by Izdavačka Akademija [The Publishing Academy] which trains young people in translation and publishing. The three publications each takes a different publishing approach to the anthologising of ten short stories, including three from English-speaking writers. Scent is now Miris and it’s a great honour to be included, as well as a warm thrill to know the work is reaching new readers. Still, it’s a curious sensation to see your work in print yet understand virtually nothing of it. It makes me wonder – should the Croatian language be something else I ought to know more about?

I have a modest facility with languages but one of the many languages I don’t know at all is Croatian. This has rarely seemed a major gap: I may harbour thoughts of holding down a conversation with the Tottenham Hotspur midfielder Luka Modric but I suspect that my contribution would be a babble of incoherent fanspeak, irrespective of the nominal lanaguage. From this week, though, my lack of Croatian will be a source of some bother due to the publication of three separate Croatian translations of my 2008 story, Scent. The translations appear, respectively, in Pandemonij, Okreni na priču and Tko tu koga? – as well as in pdf format online here – published by Izdavačka Akademija [The Publishing Academy] which trains young people in translation and publishing. The three publications each takes a different publishing approach to the anthologising of ten short stories, including three from English-speaking writers. Scent is now Miris and it’s a great honour to be included, as well as a warm thrill to know the work is reaching new readers. Still, it’s a curious sensation to see your work in print yet understand virtually nothing of it. It makes me wonder – should the Croatian language be something else I ought to know more about?

The question of what a writer should know occurs to me when I’m doing the rounds teaching Creative Writing to undergraduates. It’s not uncommon for some students to complain that they don’t really ‘do’ short stories. The short story disciplines of editing, economy, crafting a perfect sentences and realising a complete story are too much of a struggle and they honestly feel they’re more suited to the higher form of novel-writing. Of course, it’s a great thing for a person to have a novel inside them and it could well prove to be a great thing for the culture as well. The thought of showing up at University on a Creative Writing degree and bypassing all other disciplines in pursuit of this singular opus might seem strange to, say, a medical student. A student may enter medical school with dreams of curing cancer but I somehow doubt that when James Robertson Justice or Eriq La Salle tries to instruct our medic in how to perform a tracheostomy, they’re told, ‘Actually, tracheostomies aren’t really my thing – do you think I could just go to the lab and work on my cure for cancer instead?’

‘Oh, you have a cure for cancer? Tell me about it.’

‘Well, it’s really just an idea based on something I saw last week on an episode of House.’

I’ve touched on some of the areas of knowledge that might inform a writer’s work in an earlier post when I considered The Physics of Language, Dom DeLillo’s articulation of how language houses and stratifies knowledge. Professional writers will recognise the necessity of research and fact-checking for work that is to appear in the public domain, but aside from this retrospective acquisition of knowledge, is there a level of knowingness needed to become a writer? Can ‘write what you know’ be superseded by ‘know so you can write’?

The study of creative writing at university is by no means the only nor necessarily the best route towards a life in writing but not even Monty Python’s working-class playwright could deny the increased significance creative writing academia has as a crucible for contemporary literary practice. When tuition fees rise and employability becomes the function of, as opposed to a passive yardstick for, university study, creative writing degrees will come under an inevitable pressure to demonstrate their practicality as well as their popularity. Could it be time to move away from a philosophy whereby the skills needed for creative writing are taught in terms of their transferability to suit careers in anything but, towards the serious study of disciplines that could nourish and enrich the writing? I teach students who also learn Japanese or philosophy within combined honours degrees. Any crossover is purely an individual initiative – but what if those twin beds were pushed together to make one double? What if a creative writing undergraduate could spend three years writing but also drawing from research into history, chemistry, architecture, economics, astrophysics – what would knowing about any or all of this do to the words?

I don’t know if I’m arguing towards a sun-drenched ideal or from a bitter basement of despair at the absence of rigour that can characterise this particular form of paper chase, leaving the subject open to the type of ridicule that used to be reserved for media studies (and incubated, paradoxically, within the mainstream media). Maybe this isn’t a discussion any broader than my own narrow range of interests and awareness. But it’s one that will remain current for the foreseeable futute – or at least until the day your car breaks down on the road from Split to Zagreb and you decide to call a short story writer out to take a look at it.

And now we hood our enemies

to blind them. Keep an eye on that irony.[Michael Symmons Roberts, from ‘Hooded’, in The Half Healed (Cape Poetry, 2008)]

Within the Hermetic Spaces category, I’m developing the ideas around short fiction’s relationship with temporal and spatial confinement that have emerged from my Café Shorts musing and which I began to lay out in considering Anthony Doerr’s Memory Wall a few weeks ago. And, although I’m dealing with a short story in this post, Hermetic Spaces will also take in the mechanisms of writing and just being that this blog likes to discuss. The invitation to draw up a seat and join in the conversation should be taken for granted.

Hassan Blasim‘s The Reality And The Record might also have made a lateral contribution to the Reel Time Short Stories series. Blasim has released films in his native Iraq as well as in exile in Iraqi Kurdistan and since taking up residence in Finland. When I was writing that sentence, I thought twice and decided against describing Blasim as, first, a “respected” film-maker, and then a “successful” film-maker. Under dictatorship, to what does “respect” amount? In exile, what counts as “success”? The conditions Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright, writes about in his 2009 Comma Press collection The Madman Of Freedom Square, force us to interrogate platitudes and to re-consider all manner of language:

Hassan Blasim‘s The Reality And The Record might also have made a lateral contribution to the Reel Time Short Stories series. Blasim has released films in his native Iraq as well as in exile in Iraqi Kurdistan and since taking up residence in Finland. When I was writing that sentence, I thought twice and decided against describing Blasim as, first, a “respected” film-maker, and then a “successful” film-maker. Under dictatorship, to what does “respect” amount? In exile, what counts as “success”? The conditions Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright, writes about in his 2009 Comma Press collection The Madman Of Freedom Square, force us to interrogate platitudes and to re-consider all manner of language:

What I’m saying has nothing to do with my asylum request. What matters to you is the horror. If the Professor was here, he would say that the horror lies in the simplest of puzzles which shine in a cold star in the sky over this city. In the end they came into the cow pen after midnight one night. One of the masked men spread one corner of the pen with fine carpets. Then his companion hung a black banner inscribed: The Islamic Jihad Group, Iraq Branch. Then the cameraman came in with his camera, and it struck me that he was the same cameraman as the one with the first group. His hand gestures were the same as those of the first cameraman. The only difference was that he was now communicating with the others through gestures alone. They asked me to put on a white dishdasha and sit in front of the black banner. They gave me a piece of paper and told me to read out what was written on it: that I belonged to the Mehdi Army and I was a famous killer, I had cut off the heads of hundreds of Sunni men, and I had support from Iran. Before I’d finished reading, one of the cows gave a loud moo so the cameraman asked me to read it again. One of the men took the three cows away so that we could finish off the cow pen scene.

The narrator here was a Baghdad ambulance driver and is now an asylum seeker who has made his way to Sweden from the war in post-Saddam Iraq. In his testimony, he gives a graphic illustration of what might constitute a form of Hermetic Space that extends beyond a moment in time in one specific location. Certainly, the claimant has experienced confinement: he has been kidnapped, bundled into his stolen ambulance, driven over Baghdad’s Martyrs Bridge and held hostage. Prior to the video detailed in the quote above, he has already been recorded for a hostage video on behalf of his original kidnappers, before being dumped, kidnapped again by someone else and then put through the same process. He continues to be passed back and forth across Martyrs Bridge and around the terrorist organisations of Iraq: recording videos spouting a panoply of scripted confessions, each of which are filmed by the same man, whom he suspects to be the “Professor”, the eccentic director of the hospital Emergency Department for which he drove his ambulance.  The weary account of this horror story is told in tones of grim farce that bring to mind the character of Yossarian in Joseph Heller’s Catch 22. The ambulance driver’s perpetual entrapment, at the hands and in the viewfinder of these feverish, amateur content providers for Al-Jazeera’s rolling news, articulates a locked-in state and it’s only escape and the chance of asylum that offers a resolution.

The weary account of this horror story is told in tones of grim farce that bring to mind the character of Yossarian in Joseph Heller’s Catch 22. The ambulance driver’s perpetual entrapment, at the hands and in the viewfinder of these feverish, amateur content providers for Al-Jazeera’s rolling news, articulates a locked-in state and it’s only escape and the chance of asylum that offers a resolution.

However, it’s not simply the condition of kidnap victim that indicates a narrative unfolding within a Hermetic Space. The claim, that the war is being conducted as a Mexican stand-off on YouTube with most hits wins, cannot be taken as the truth, can it? Who is to know what the truth is of the man’s account? A fantasy wrought from the dislocating experience of kidnap? An elaborate cover-up for atrocities of his own? The story he thought he would need to secure asylum? Or even just a truth too unpalatable to be admissable? In zeroing in on the way war renders reality an impossibility to gauge, Blasim’s story is a good accompaniment to Tim O’Brien’s 1990 insertion of a Vietnam War tale into a narrative hall of mirrors, How To Tell A True War Story. It also points to the way in which War itself can be a narrative sealant, within which short stories can show us not so much the fixtures and fittings of a given conflict but a portrait of the human condition caught in a rapture of inhumanity.

Still from the final part of Masaki Kobayashi's Japanese WW2 trilogy, "Ningen No Joken III" ("The Human Condition")

We leave the last word to the Professor: ‘The world is just a bloody and hypothetical story. And we are all killers and heroes.’

Splashback Sequences

Posted on: October 1, 2011

The picture here is misleading. This post deals with stimuli for short stories and the picture may, in this context, seem to suggest that a visit to the world-famous Gents’ toilets in Liverpool’s Philharmonic Pub provided me with the inspiration for the central character in one of my stories. This would be nonsense.  They don’t have attendants in the Phil’s toilets: there’s no room. There was, however, one on duty in the barely more spacious Gent’s at the Alma de Cuba bar in town, when I was in there for a drink a few years ago. I had occasion to tell this story at the recent Merseyside Polonia event mentioned in an earlier post. The young African man manoeuvering himself around the tight space to offer me a squirt of aftershave – maybe a student, maybe a migrant worker – found his way into the story that appeared as Scent in Comma’s 2008 ReBerth anthology.

They don’t have attendants in the Phil’s toilets: there’s no room. There was, however, one on duty in the barely more spacious Gent’s at the Alma de Cuba bar in town, when I was in there for a drink a few years ago. I had occasion to tell this story at the recent Merseyside Polonia event mentioned in an earlier post. The young African man manoeuvering himself around the tight space to offer me a squirt of aftershave – maybe a student, maybe a migrant worker – found his way into the story that appeared as Scent in Comma’s 2008 ReBerth anthology.

Those who stop to hover over the bottles never ask his advice as to which scent they should wear. He would recommend that they find the one they came out with, not attempt to mask the new smells they’ve acquired from the drinks and the smokers’ doorways, with something even more pungent. He would suggest that these layers build to give a fragrance that stiffens the air they move through. He worries about what it does to the water; wonders what a squirt of Hugo Boss will do to the ancient mating rituals of the eels that find their ways into the estuary. The men, when they speak to him, call him ‘mate’; they call him ‘lad’. Two or more of them visiting the toilet together will stand either side of him to continue their conversations, like neighbours on adjoining balconies.

The experiences that go into a story – like the aromas of the drinkers – are built, layer upon layer, so the image of this marginalised figure in an unpleasant service industry job gave me a character and a way into his psychology. The narrative I gave him, though, came from my own experience nearly 20 years earlier, when my unfurnished housing association flat, in which I had only managed to install a single bed, was suddenly equipped with chairs, desks and cupboards worth far more than the £50 cash I paid.  My Magwitch-on-wheels lived across the corridor but, as in the story, he was in a hurry to get rid of the furniture, move out and leave town using the nominal fee I was paying. The reason he gave for his departure; the items of furniture; the window that had to be opened to get the enormous seventies couch in; and the neighbour’s trademark chariot races up and down Princes Avenue on a skateboard pulled by two dogs, the stuff of local legend: all details were lifted from real life and placed, more or less intact, in the story. Elsewhere, a scene in which the main character discusses jellyfish with a small boy and his father, at the Albert Dock, came first from the excitement of spotting the jellies with my own son on a visit to the Dock, then from research after I decided that the main character would have some expertise in marine biology, in its turn a layer suggested by the commission’s call for stories relating to the water and the edge of land.

My Magwitch-on-wheels lived across the corridor but, as in the story, he was in a hurry to get rid of the furniture, move out and leave town using the nominal fee I was paying. The reason he gave for his departure; the items of furniture; the window that had to be opened to get the enormous seventies couch in; and the neighbour’s trademark chariot races up and down Princes Avenue on a skateboard pulled by two dogs, the stuff of local legend: all details were lifted from real life and placed, more or less intact, in the story. Elsewhere, a scene in which the main character discusses jellyfish with a small boy and his father, at the Albert Dock, came first from the excitement of spotting the jellies with my own son on a visit to the Dock, then from research after I decided that the main character would have some expertise in marine biology, in its turn a layer suggested by the commission’s call for stories relating to the water and the edge of land.

We are so many of the characters in the stories we write. When casting about for narratives, remember what you’ve glimpsed and what you’ve lived. Having dragged this discussion into the toilets, I’m going to stay there for this thought on how an incident devoid of real narrative substance can, with some aftercare, set you on the path to a story.  In a different bar at a different time – on this occasion for a 40th birthday party – but once more in the Gent’s, I met Jed (centre), who used to be in the band, The Stairs. After the initial how’re-you-doing, we admitted to each other that, though we’d both known the birthday girl since we were all teenagers, neither of us knew her surname. Subsequently, I’ve considered that it’s equally the case that I wouldn’t know Jed’s surname without the aid of Google, and he would probably have the same problem with me. Nothing much to report here: it doesn’t matter to anyone, this long-term, arm’s length sociability. But what if it did matter? What if the recollection of an old acquaintance’s surname was the difference between safety and danger? What kind of story would we be telling then?

In a different bar at a different time – on this occasion for a 40th birthday party – but once more in the Gent’s, I met Jed (centre), who used to be in the band, The Stairs. After the initial how’re-you-doing, we admitted to each other that, though we’d both known the birthday girl since we were all teenagers, neither of us knew her surname. Subsequently, I’ve considered that it’s equally the case that I wouldn’t know Jed’s surname without the aid of Google, and he would probably have the same problem with me. Nothing much to report here: it doesn’t matter to anyone, this long-term, arm’s length sociability. But what if it did matter? What if the recollection of an old acquaintance’s surname was the difference between safety and danger? What kind of story would we be telling then?

Or what if Jed and I had met in the toilets of a venue in which there were two 40th birthday parties taking place in separate rooms? That he was talking about one Sarah, whose surname he didn’t know, and I was talking about another? The thriller of the earlier scenario becomes surrealist farce or Kafkaesque dystopia.

I have in the past week or so, renewed my acquaintance with, or newly encountered, groups of creative writing undergraduates charged in the coming weeks with overcoming the tyranny of the blank page. It’ll help them to remember that stories can start to appear if they took a look at their real lives, picked up a memory – that encounter, that image, that could-have-been that almost turned into a what-now? – and just added a quick squirt of what-if? to freshen it up.

Two Such Things As A Free Gig

Posted on: September 22, 2011

News of two free events at which I’ll be reading this week:

This evening (Thurs 22nd Sept) sees the first in a series of monthly events, hosted by Merseyside Polonia, an organisation working to bridge the social and cultural gaps between the established local community in Liverpool and those more recently arrived from Poland. My Favourite Book will be a chance to discuss and read from world literature, with a particular emphasis on British and Polish literature in translation.

This evening (Thurs 22nd Sept) sees the first in a series of monthly events, hosted by Merseyside Polonia, an organisation working to bridge the social and cultural gaps between the established local community in Liverpool and those more recently arrived from Poland. My Favourite Book will be a chance to discuss and read from world literature, with a particular emphasis on British and Polish literature in translation.

As special guest for the first event tonight, I’ll be discussing my own story, Scent, published in the 2008 Comma Press anthology, ReBerth: Stories from cities on the edge, which also featured stories by Paweł Huelle and Adam Kamiński from Gdansk. Scent deals with the settlement experience of a migrant in Liverpool, working as a toilet attendant in a waterfront bar by night, and coming home to his unfurnished flat and the dramas of the couple in the neighbouring flat.

As special guest for the first event tonight, I’ll be discussing my own story, Scent, published in the 2008 Comma Press anthology, ReBerth: Stories from cities on the edge, which also featured stories by Paweł Huelle and Adam Kamiński from Gdansk. Scent deals with the settlement experience of a migrant in Liverpool, working as a toilet attendant in a waterfront bar by night, and coming home to his unfurnished flat and the dramas of the couple in the neighbouring flat.

The event is at Kensington Fire Station, Beech Street, Liverpool L7 0EU; 6.30-8.30pm.

Again in Liverpool, on Sunday 25th September, at around 1.30pm, I’ll be reading on the spoken word stage at the 2011 Bold Street Festival, which takes place over the weekend.

Again in Liverpool, on Sunday 25th September, at around 1.30pm, I’ll be reading on the spoken word stage at the 2011 Bold Street Festival, which takes place over the weekend.

Most artists in Liverpool hold Bold Street dear to their hearts; for followers of my Café Shorts series, it’s long been the cornerstone of the sitting, sipping and dreaming scene; while shops like Matta’s International Foods and the brilliant News From Nowhere book shop help it to retain the identity of being a part of “our town” even as the chains and developers gobble up the rest of the city centre.

That said, I’ll be performing next to Tesco’s!

Nevertheless, if you’re in Liverpool, come along and support these events…