Posts Tagged ‘edgar allen poe’

Ten years ago, the particular context in which the British government chose to make April Fools of its citizens was the war in Iraq. This year, Iraq would seem a very exotic focal point for our denigration when the current government is so busy reducing our domestic certainties – a health service, a welfare state, a justice system – to the status of a blooper reel among the Extras on Michael Gove’s History of Great Britain DVD. When we’re losing track of who we are, of why we even exist as social animals, it is a challenge to contemplate the experience of Iraqis, by whom reality has, during these ten years, been viewed in a perpetual nightmarish REM. Yet Hassan Blasim‘s second collection for Comma Press speaks to our own, particularlised sensations of powerlessness, as much as to the self-evident contexts of war, exile and the way these narratives of suffering become absorbed into a nation’s culture and myths.

Ten years ago, the particular context in which the British government chose to make April Fools of its citizens was the war in Iraq. This year, Iraq would seem a very exotic focal point for our denigration when the current government is so busy reducing our domestic certainties – a health service, a welfare state, a justice system – to the status of a blooper reel among the Extras on Michael Gove’s History of Great Britain DVD. When we’re losing track of who we are, of why we even exist as social animals, it is a challenge to contemplate the experience of Iraqis, by whom reality has, during these ten years, been viewed in a perpetual nightmarish REM. Yet Hassan Blasim‘s second collection for Comma Press speaks to our own, particularlised sensations of powerlessness, as much as to the self-evident contexts of war, exile and the way these narratives of suffering become absorbed into a nation’s culture and myths.

A simple summary of The Iraqi Christ: this is the most urgent writing you will read in short fiction or any other literary format this year. To read these stories is to immerse yourself in tragedy and horror. The imprint of real lives – Blasim’s and those he has encountered – is as evident on the printed page here as lipstick traces on a cigarette, exacerbating the sense of grief that accompanies each story. Blasim’s debut collection for Comma, 2009’s The Madman Of Freedom Square (from which “The Reality and the Record” provided a previous post for this site), was an eloquent, retching cry of disgust; The Iraqi Christ seems to be steeped more in sorrow. And the incredible part is that, from this unimaginable sorrow, what emerges is a savage, unbearable beauty.

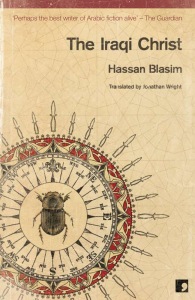

The stories portray characters locked in states of fretful, at times lurid, sensory dissonance. If you knew nothing of this book or Blasim’s literary antecedents other than David Eckersall’s cover design, pictured above, you might guess that Franz Kafka sits somewhere in the frame of reference. Short fiction routinely converses with its ghosts and Kafka’s presence is almost that of a recurring character, most conspicuously in The Dung Beetle, an overt reference to Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, with the concerns of the changeling Gregor Samsa, conceived during the First World War, transposed onto those of an Iraqi now residing in Finland, inside a ball of dung. In relating his fictional counterpoint’s story, Blasim makes what I take to be a more direct authorial interjection:

A young Finnish novelist once asked me, with a look of genuine curiosity, ‘How did you read Kafka? Did you read him in Arabic? How could you discover Kafka that way?’ I felt as if I were a suspect in a crime and the Finnish novelist was the detective, and that Kafka was a Western treasure that Ali Baba, the Iraqi, had stolen. In the same way, I might have asked, ‘Did you read Kafka in Finnish?’

Such is the sense of dislocation and depersonalisation, of inurement to brutality and reduction to absurdity, reading Kafka seems less of a choice or privilege than a routine motor function. The Dung Beetle quotes in full Kafka’s Little Fable in which a mouse articulates the essential condition of the Kafkaesque protagonist:

The mouse said, ‘Alas, the world gets smaller every day. It used to be so big that I was frightened. I would run and run, and I was pleased when I finally saw the walls appear on the horizon in every direction, but these long walls run fast to meet each other, and here I am at the end of the room, and in front of me I can see a trap that I must run into.,

‘You only have to change direction,’ said the cat, and tore the mouse up.

The earlier Ali Baba reference directs us to Blasim’s coupling of Kafka with Sheherazade and the One Thousand and One Nights tales, for which the narrative of the young bride using her powers of storytelling to stave off the daily threat of execution is the framing device, an appropriate analogy when claiming asylum.  The deadpan depravity in The Hole exemplifies how these strands become twisted together. The narrator, on the run from masked gunmen as chaos greets the collapse of the government, falls into a hole and encounters a “decrepit old man”, claiming to be a djinni (genie) and calmly carving chunks of flesh to eat from the corpse of a soldier who has previously fallen down the hole. There is no escape and the company only emphasises how divorced this place is from the reality the narrator has known.

The deadpan depravity in The Hole exemplifies how these strands become twisted together. The narrator, on the run from masked gunmen as chaos greets the collapse of the government, falls into a hole and encounters a “decrepit old man”, claiming to be a djinni (genie) and calmly carving chunks of flesh to eat from the corpse of a soldier who has previously fallen down the hole. There is no escape and the company only emphasises how divorced this place is from the reality the narrator has known.

In the 1001 Nights tale of Sinbad’s fourth voyage – several years into his latest enforced sojourn in a land in which he has initially been made to feel welcome and has become happily married – he learns of the bizarre local custom that, when a married man or woman dies, the living spouse is also thrown into the huge pit, that serves as a mass grave, accompanied by the humane provision of a spartan packed lunch for pre-death nourishment. Sinbad’s wife falls ill and dies and, sure enough, both her body and the breathing, protesting form of Sinbad are thrown in the pit. Sinbad survives in his pit of corpses by clubbing any newly-widowed arrival to death with a leg-bone and taking their bread and water for sustenance. These echoes cement Blasim’s storytelling within the traditions of the region but the stories that fuel his writing are timeless and universal, relating to the stark choices facing humans when everything that betokens their humanity has been stripped away. Italo Calvino is another writer cited, via his Mr Palomar character, who painstakingly seeks to quantify the contents of a disparate universe; when ‘Hassan Blasim’ appears as a character, shifting the boundaries of reality in Why Don’t You Write A Novel Instead Of Talking About All These Characters?, there are shades of Paul Auster’s introspections about the nature of truth and story. Where – in, for example, the meta-gumshoe story City Of Glass, itself Edgar Allen Poe’s The Man Of The Crowd by way of, yes, Kafka – Auster will use a character called ‘Paul Auster’ to interrogate the identity of the “I” in whose Point of View the story is being told, it’s couched within the ‘what-if?’ framework we might expect to find in any fictional narrative. Blasim operates from a starting-point in which life has already become that fiction. This is an object lesson for those who assume that it would be enough to transcribe and dust-jacket the extraordinary circumstances of their own lives in order to produce a compelling narrative. Blasim’s life enters Blasim’s fiction as a kind of exorcism: you don’t want to explore how much is actually a record of the truth because you can’t bear to look. In Why Don’t You Write A Novel…?, the narrator makes a prison visit to the man with whom he made the journey to escape Iraq and claim asylum in Europe. Along the way, this companion, Adel Salim, inexplicably murdered a drowning man whom they had met on the refugee trail:

‘Okay, I don’t understand, Adel,’ I said. ‘What were you thinking? Why did you strangle him? What I’m saying may be mad, but why didn’t you let him drown by himself?’

After a short while, he answered hatefully from behind the bars. ‘You’re an arsehole and a fraud. Your name’s Hassan Blasim and you claim to be Salem Hussein. You come here and lecture me. Go fuck yourself, you prick.’

The narrator, aware only of his work as a translator working in the reception centre for asylum seekers, retreats in confusion and struggles to recover memories from before his border crossing. In an encounter on a train, a man, carrying a mouse, identifies him as the author of several stories, including some of those contained in this collection. I don’t know whether Blasim was setting out to articulate this but there’s a particular bleakness to the writing life when you feel you’re holding the weight of all the blood and bones in the world but the only place you have to set it down is something so light and flimsy as the page of a book.

For all the postmodernism and the literary conversations, and the insect and, for Dear Beto, canine narrators, we are taken goosebump-close to what happens in everyday human lives in a protracted war situation, with Jonathan Wright’s translations ensuring no walls remain between these characters and the reader. The Iraqi Christ is eye-catchingly provocative as a title for the book but the story bearing that name provides a more straightforward explanation: it’s a reference to Daniel, an Iraqi soldier who’s a practising Christian and committed gum-chewer so known to his fellow soldiers as the Chewgum Christ, Christ for short. The story, though, we come to realise, is a kind of gospel told by a beyond-the-grave narrator who relates the miraculous, almost unconscious prescience with which this Iraqi Christ manages to evade death, to the point that he takes on a talismanic role among his comrades. A life avoiding death isn’t quite the same as a life, though, and there is sacrifice and redemption to follow in an ending that is built on tragic irony but has a strangely uplifting choreography to it.

For all the postmodernism and the literary conversations, and the insect and, for Dear Beto, canine narrators, we are taken goosebump-close to what happens in everyday human lives in a protracted war situation, with Jonathan Wright’s translations ensuring no walls remain between these characters and the reader. The Iraqi Christ is eye-catchingly provocative as a title for the book but the story bearing that name provides a more straightforward explanation: it’s a reference to Daniel, an Iraqi soldier who’s a practising Christian and committed gum-chewer so known to his fellow soldiers as the Chewgum Christ, Christ for short. The story, though, we come to realise, is a kind of gospel told by a beyond-the-grave narrator who relates the miraculous, almost unconscious prescience with which this Iraqi Christ manages to evade death, to the point that he takes on a talismanic role among his comrades. A life avoiding death isn’t quite the same as a life, though, and there is sacrifice and redemption to follow in an ending that is built on tragic irony but has a strangely uplifting choreography to it.

Further evidence of unexpected uplift comes in the final story, A Thousand and One Knives, a magic realist story of a team of street magicians whose ability to make knives disappear into thin air and then bring them back operates as a twin process of exorcism (again) and healing. The team have found one another through their gifts and rub along as a dysfunctional family group. In an attempt to understand what the trick of disappearing and reappearing knives might mean, the narrator is charged with researching the subject:

It was religious books that I first examined to find references to the trick. Most of the houses in our sector and around had a handful of books and other publications, primarily the Quran, the sayings of the Prophet, stories about Heaven and Hell, and texts about prophets and infidels. It’s true I found many references to knives in these books but they struck me as just laughable. They only had knives for jihad, for treachery, for torture and terror. Swords and blood. Symbols of desert battles and the battles of the future. Victory banners stamped with the name of God, and knives of war.

In the face of this understanding of knives, the group use their skills very little for show and not at all for profit but as a compulsion, like the stories of Sheherazade, because there are things that need to happen, because not doing it is too horrific to contemplate. When we learn of the baby born to the narrator and Souad, the only woman in the group and the only one able to make knives reappear, we see that they have cut themselves into one another’s flesh as well, in acts of transformative love and friendship that – remarkably, by the end of this remarkable collection – allow the reader to emerge with hope still intact, battered, but somehow reinforced.

The Iraqi Christ by Hassan Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright, supported by the English PEN Writers In Translation programme, is published by Comma Press and available in book and e-book form.

I’ve found that people who’ve read stories by Roberto Bolaño tend to have stories to tell about Roberto Bolaño. These stories are inevitably about ourselves, our own life stories and the stories of those in our lives.

I’ve found that people who’ve read stories by Roberto Bolaño tend to have stories to tell about Roberto Bolaño. These stories are inevitably about ourselves, our own life stories and the stories of those in our lives.

The first time anyone ever told me about Bolaño was when I had a chance meeting with my friend K, on Bold Street, which anyone in the Liverpool art scene knows is the street on which chance meetings are inevitable, so not really chance at all, and it’s really the only place I see K these days. K is a Glaswegian former Situationist, a playwright and DJ – at the legendary Eric’s in the punk era and on Toxteth pirate radio stations in the 90s, which is when I got to know him well, though our paths had first crossed as adult literacy tutors in the back end of the 80s. He set up the annual African and Latin American music festival in Liverpool and I’m used to him recommending artists to me whose names sound like songs – Orchestre Baobab, Oumou Sangaré, Lisandro Meza, Zaiko Langa Langa – and, to be truthful, the words “Roberto Bolaño” similarly washed over me as a melodic statement rather than a name to follow up. What did stick with me was that there was a buzz about a novel by this writer, that the work was unfeasibly ambitious and certainly messy but, K told me, “some of the things he does with prose” justified the hype. Slightly closer attention to the susurrus from the literary salon told me that the novel was Bolaño’s five-part, posthumously published 2666, so I got hold of a copy. In the spring of 2009, I began reading it in the café of Liverpool’s World Museum while waiting for a meeting about the Charles Darwin-inspired Evolving Words workshops I would be facilitating there over the summer.

The story of how I came by Bolaño now becomes a different story, not really a story about friendship and meetings and work and time, but a story about writing; it’s about reading and it’s about being a writer; it’s about being this writer and not being that writer. That’s why I am using these stories as a preamble – in case you were losing faith in my remembering the title of this post – to talking about Bolaño’s short story, A Literary Adventure from the similarly posthumous 2008 collection, Last Evenings On Earth: because any story I tell about Bolaño should rightfully mention the story about when I was reading 2666 and my head spun round in a complete circle.

I began reading with thoughts of K’s paean about the quality of ideas in the prose. For eight-and-a-half pages, I was conscious of the lack of spectacle. The writing was fluid, engaging, and the story was interesting. I don’t know what exactly I was looking for – I had the experience built up as something akin to a first hearing of a musical revolutionary like Sun Ra or Ornette Coleman, but what might that be like in prose fiction, with words on the mortuary slab of a page? If a work of prose is like a building, then in these early few pages I was still in the hallway of the prose, able to admire only the basic masonry and door hinges of the text. Then, on page 9, a character called Liz Norton, an English academic in an Oxford college, began reading a novel by an obscure German writer, Benno von Archimboldi:

She read it, liked it, went to her college library to look for more books by the German with the Italian name, and found two: one was the book she had already read in Berlin, and the other was Bitzius. Reading the latter really did make her go running out. It was raining in the quadrangle, and the quadrangular sky looked like the grimace of a robot or a god made in our own likeness. The oblique drops of rain slid down the blades of grass in the park, but it would have made no difference if they had slid up. Then the oblique (drops) turned round (drops), swallowed by the earth underpinning the grass, and the grass and the earth seemed to talk, no, not talk, argue, their incomprehensible words like crystallized spiderwebs, or the briefest crystallized vomitings, a barely audible rustling, as if instead of drinking tea that afternoon, Norton had drunk a steaming cup of peyote.

[translation by Natasha Wimmer]

And that was when my head performed a 360.

The willingness to perform prosal trapeze acts is the facet of Bolaño that first grabbed me but even the rococo stylings of the above passage give indications of some of the staple concerns in his writing. There, creeping in at the last in the reference to peyote, is the Latin American sensibility, one that is dropped – here via the Englishwoman reading the “German with an Italian name” – into a European setting where such identities drift, maybe disappear, maybe re-settle, often co-ordinate themselves in a foreign place around a sense of artistic belonging, yet are always in the grip of home. Bolaño was 20 when, on September 11th 1973, General Augusto Pinochet’s CIA-backed coup deposed the government of Salvador Allende and proceeded to brutalise the Chilean people for the next seventeen years. As one of the exiled, Bolaño carried into his writing the certainty of impermanence – endings rarely provide closure – and the sense that somehow life is a thing that’s already been lost. As liver failure led towards his early death, aged 50, this must have darkened the shadows under each tender observation of the artistic existence.

The willingness to perform prosal trapeze acts is the facet of Bolaño that first grabbed me but even the rococo stylings of the above passage give indications of some of the staple concerns in his writing. There, creeping in at the last in the reference to peyote, is the Latin American sensibility, one that is dropped – here via the Englishwoman reading the “German with an Italian name” – into a European setting where such identities drift, maybe disappear, maybe re-settle, often co-ordinate themselves in a foreign place around a sense of artistic belonging, yet are always in the grip of home. Bolaño was 20 when, on September 11th 1973, General Augusto Pinochet’s CIA-backed coup deposed the government of Salvador Allende and proceeded to brutalise the Chilean people for the next seventeen years. As one of the exiled, Bolaño carried into his writing the certainty of impermanence – endings rarely provide closure – and the sense that somehow life is a thing that’s already been lost. As liver failure led towards his early death, aged 50, this must have darkened the shadows under each tender observation of the artistic existence.

I Take Back Everything I’ve Said

Before I go

I’m supposed to get a last wish:

Generous reader

burn this book

It’s not at all what I wanted to say

Though it was written in blood

It’s not what I wanted to say.

No lot could be sadder than mine

I was defeated by my own shadow:

My words took vengeance on me.

Forgive me, reader, good reader

If I cannot leave you

With a warm embrace, I leave you

With a forced and sad smile.

Maybe that’s all I am

But listen to my last word:

I take back everything I’ve said.

With the greatest bitterness in the world

I take back everything I’ve said.[Nicanor Parra; translated by Miller Williams]

It’s possible that a story like A Literary Adventure, translated by Chris Andrews, might seem a meandering tale of obsession, a more loosely-structured take on Edgar Allen Poe’s seminal shadow-chaser, The Man Of The Crowd but without the pay-off of Poe’s final, frustrated confrontation. This is more than a case of Bolaño spinning a shaggy dog story: the marginalised writer moves with a shambling gait through most of Bolaño’s stories, whether as stand-ins for the writer himself, or personified by the almost mythic figure of Archimboldo, or emerging from the pages of forgotten literary journals picked up in thrift shops by the characters in the short stories. It’s not difficult, as a writer, to relate to such figures because we all have our sense of marginalisation; of being overlooked in favour of other lesser, or if not lesser then luckier, or if not luckier then simply younger talents; or of – whatever level of satisfaction we may have with our own relative status – griping that there is insufficient regard for what we do because the public is misdirected as to why, how and what to read. For the most part, these miseries can be absorbed, comfortably and productively, into a world-view laced with a generous and genial scepticism but Bolaño provides catharsis because he never absorbed that stuff: it bounced straight onto the page.

Benjamin Samuel, blogging about literary feuds, cites Bolaño’s pronouncement on the Argentinian writer, Osvaldo Soriano: “You have to have a brain full of fecal matter to see him as someone around whom a literary movement can be built.”It’s in this context of affronted ego mixed with wounded self-doubt that A Literary Adventure takes shape. As elsewhere in his short stories, Bolaño’s protagonist is simply identified as B. There is an antagonist, as unwitting a nemesis as the suspicious-looking old man trailed by Poe’s narrator, referred to as A. These may well be substitutes for Bolaño and a specific contemporary, but they are archetypes as well. A is:

a writer of about B’s age, but who, unlike B, is famous, well-off and has a large readership; in other words he has achieved the three highest goals (in that order) to which a man of letters can aspire. B is not famous, he has no money and his poems are published in little magazines.

I know I’m a B; to my friends and acquaintances and Facetwitter whatever whatevers, if I’m more in the A category to you, then I beg your forgiveness but, you know, you should get out more because there are some real As out there and each of them considers his or herself a B in relation to someone else again. The details that inject this story with the pain of a chord played by Victor Jara are phrases like the “in that order” ranking of writerly aspirations, or the heartbreaking diminuitive “little magazines”. So personal disappointment is fused with a righteous sense that success is lavished on the undeserving, or that it corrupts. B notices “a sanctimonious tone” appearing in A’s writing as his recognition grows and it’s this pomposity he attacks when creating Medina Mena, a thinly-veiled representation of A, for one chapter of a novel he is writing (presumably because poetry isn’t paying). The novel is picked up for publication and sent out for reviews. A is a reviewer – an influential one, at that – and he loves B’s book. While singing its praises, he appears not to recognise, or at least publicly to acknowledge, the satirical version of himself B has written.

The story revolves around the moral crisis A’s enthusiastic review triggers in B’s conscience and imagination. The layering of speculation upon assumption here is an utterly believable depiction of B’s mounting paranoia:

He’s praising my book to the skies, thinks B, so he can let it drop back to earth later on. Or he’s praising my book to make sure no one will identify him with Medina Mena. Or he hasn’t even realised, and it was a case of genuine appreciation, a simple meeting of minds. None of these possibilities seems to bode well.

Neurosis makes for great, bleak comedy and there’s a Picaresque feel – B as a hapless Gulliver in the land of Spanish literature – to the way the plot spools through B’s efforts to get to know A and thereby get to the truth of exactly what he felt about the Medina Mena character. There is the publication of B’s second novel and A’s equally warm, though suspiciously swift, review of that. There is a party in which a meeting with A seems about to take place in a dark recess of a garden which Chekhov might have fashioned to represent a soul in torment. And there are phonecalls made at inappropriate times, visits planned, voices overheard, all of which seem to be inching us towards a resolution.

But B’s identity as a writer must leave agonies like this unresolved. This story isn’t what matters anyway: what matters are the stories that happen in the corner of your eye while you’re keeping watch on something you should ignore. When following A but deliberating on whether to try to speak to him, B goes to a restaurant and, for a few minutes as he eats, we sense a respite from the literary frustration that’s eating away at him. Could the story have been here instead?

B sits down next to the window, in a corner away from the fireplace, which is feebly warming the room. A girl asks him what he would like. B says he would like to have dinner. The girl is very pretty. Her hair is long and messy, as if she just got out of bed. B orders soup, and a meat and vegetable dish to follow.

The next sentence – “While he is waiting he reads the review again.” – sucks him back into his grim quest but in that sliver of life in the restaurant, that moment of survival and possible hope for more than mere survival, we glimpse the beauty of Bolaño’s storytelling. We get that his stories and our own swim around one another, with beginnings that are impossible to trace and no resolution in the endings, just these moments that happen on the way to the end.

My good friend O, a songwriter, guitarist and drummer, was another Chilean who left the country after youthful struggles against Pinochet. Before he arrived in Liverpool, he spent some time in Spain, where A Literary Adventure and other Bolaño stories are set. He hasn’t read Bolaño but he has a story he wants to tell about the beautiful Madrileña daughter who recently stepped out of his past. I want him to read Last Evenings On Earth as he sets about writing down his stories. Because he’s in Bolaño’s stories and because Roberto Bolaño is in his. Because that’s the way Bolaño’s writing works: it’s intravenous. I read Bolaño and I glimpse beauty in small moments of survival but I read Bolaño and I feel the volume of self-doubt that’s in all writers’ libraries easing itself off the shelf and dropping onto my lap. And that’s too overwrought a metaphor, isn’t it, making the process sound like The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. And I’ve made this blog too long so readers will probably cut out after they click on the Sun Ra link I inserted earlier, so then that’ll be yet another thing to add to the list of all the other things.

It’s been marking season, blending into the new teaching semester at the various universities in and out of whose payroll I flit, leaving this blog short of even the single hand it normally occupies. If I had three wishes, it would be for a few extra days each week to remember the life that one’s work is meant to support and supplement. However, the story I’ve been using for teaching purposes this week has taught me to be wary of wishes.

It’s been marking season, blending into the new teaching semester at the various universities in and out of whose payroll I flit, leaving this blog short of even the single hand it normally occupies. If I had three wishes, it would be for a few extra days each week to remember the life that one’s work is meant to support and supplement. However, the story I’ve been using for teaching purposes this week has taught me to be wary of wishes.

W.W. Jacobs’ 1902 macabre masterpiece, The Monkey’s Paw, was Hammer horror back when cinema was old enough only for the PGs. That it’s an object lesson in how to while away a cold, dark night, when a fearsome wind is gathering, is evident by the adaptations, copycat narratives and Simpsons Halloween hommages it has inspired over the years. Jacobs, a whimsical Londoner whose stock-in-trade as a writer was humour, had a light enough touch to issue stagey winks to the gallery while ratcheting up the terror:

W.W. Jacobs’ 1902 macabre masterpiece, The Monkey’s Paw, was Hammer horror back when cinema was old enough only for the PGs. That it’s an object lesson in how to while away a cold, dark night, when a fearsome wind is gathering, is evident by the adaptations, copycat narratives and Simpsons Halloween hommages it has inspired over the years. Jacobs, a whimsical Londoner whose stock-in-trade as a writer was humour, had a light enough touch to issue stagey winks to the gallery while ratcheting up the terror:

Mr. White took the paw from his pocket and eyed it dubiously. “I don’t know what to wish for, and that’s a fact,” he said slowly. “It seems to me I’ve got all I want.”

“If you only cleared the house, you’d be quite happy, wouldn’t you?” said Herbert, with his hand on his shoulder. “Well, wish for two hundred pounds, then; that’ll just do it.”

His father, smiling shamefacedly at his own credulity, held up the talisman, as his son, with a solemn face somewhat marred by a wink at his mother, sat down at the piano and struck a few impressive chords.

“I wish for two hundred pounds,” said the old man distinctly.

A fine crash from the piano greeted the words, interrupted by a shuddering cry from the old man. His wife and son ran toward him.

“It moved, he cried, with a glance of disgust at the object as it lay on the floor. “As I wished it twisted in my hands like a snake.”

“Well, I don’t see the money,” said his son, as he picked it up and placed it on the table, “and I bet I never shall.”

It’s the stuff of spoof sketch shows, when Bernard Herrmann’s score for Hitchcock’s Psycho plays while a young woman takes a shower: as the music builds, so does her anxiety until with a shriek she pulls back the curtain…to reveal a sheepish string quartet. Herbert White’s ironic piano tells us that this is no primitive discovery of the spine chiller but a knowing piece of writing, whose three-act structure enables the hermetic space of the small parlour in Laburnam Villa to waver and warp like the minds of poor Mr and Mrs White after Sergeant-Major Morris offers them a furry fist-pound.

The story’s three acts work in the manner of a stage illusion. We have the pledge in act one, locating us in the type of story this is, with enough eye-catching vagary to stop us looking too hard: the ghostly ambience (but what part really does the foul weather and remote location play in the events that follow?); the traumatised visitor with the harrowing tale relating to his mysterious gift (why has he not burned it himself? why does he give it to them? what happened to him?); the first, modest wish for two hundred pounds, the equivalent of the sort of money that, on Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? would do very nicely, Chris, to pay off the debts and maybe get a little holiday. The third act, the prestige, tells us what the illusionist has done: in this case, have the Whites – or the readers, or all – believing in magic monkey paws engineering freak fatal workplace accidents and bringing mutilated zombies out of the ground to bang on front doors, but answering no questions as to what actually has taken place.

It’s the middle act, the turn, that deserves more attention for its writing sleight-of-hand. In narrative terms, the point of this section is to show us that, when the Whites wish on the monkey’s paw for two hundred pounds, the consequences were that their son, Herbert, was tragically and horrifically killed (“Caught in the machinery” of both factory and plot – a zeugma so satisfying, Jacobs makes sure it’s repeated in the dialogue), the compensation amounting to the very sum for which they wished. It’s a development that could have been reported in a couple of sentences but instead Jacobs gives a bravura display of dramatic irony, heightening every moment as the contentment built over a shared lifetime is cut away from the Whites like the paw from the monkey’s arm, and shredded like Herbert on the Maw and Meggins’ factory floor.

We’ve bolted down the jovial family breakfast, laughing off the silliness of the previous evening before Herbert takes his comedy routine off to work with him, but when, later, Mrs White is distracted by a strange, well-dressed young man at the front gate, Fate shudders to a halt and turns, slowly, gravely, to set off on its new direction:

His wife made no reply. She was watching the mysterious movements of a man outside, who, peering in an undecided fashion at the house, appeared to be trying to make up his mind to enter. In mental connection with the two hundred pounds, she noticed that the stranger was well dressed and wore a silk hat of glossy newness. Three times he paused at the gate, and then walked on again. The fourth time he stood with his hand upon it, and then with sudden resolution flung it open and walked up the path. Mrs. White at the same moment placed her hands behind her, and hurriedly unfastening the strings of her apron, put that useful article of apparel beneath the cushion of her chair.

There are so many joys in this paragraph. We’ve earlier learned that only two houses on the road are let so why paying a visit to one of them should be the cause of such uncertainty is beyond me. Of course, the reason for the young man’s dithering is to stoke Mrs White’s anticipation – she senses money in the young man’s dress – and foreboding. Note how the phrases are stretched out like pizza dough: “a silk hat of glossy newness” rather than a new silk hat; the absurd but brilliant aside about the apron – “that useful article of apparel” – as its strings are unfastened (ever tried doing that in a hurry behind your back?) and it’s shoved behind a cushion because you don’t receive visitors looking like you’re in the middle of the housework. Even when he’s inside, the visitor is given a quick inventory of everything in the house that’s not as spick and span as it ought to be, and when he starts to tell them about Herbert, he stammers, hesitates, and throws in a really bloody helpful riddle, about how Herbert is not in any pain, before getting round to the terrible news. Mr White’s reaction is beautiful:

He sat staring blankly out at the window, and taking his wife’s hand between his own, pressed it as he had been wont to do in their old courting days nearly forty years before.

In this instant, the two of them revert to a time when they were filled with hope for the future, that has since come and is now gone; they are back to when it was just the two of them, as it will be again from now on; and they are reminded of being the age Herbert was until the machinery got hold of him. It’s immaculate use of a detail whose humanity would be stunning to encounter in any story, let alone one with generic supernatural trappings. The subject of compensation comes up and Mr White’s reaction is again one to cherish, a true ‘is this your card?’ moment as he recognises the trick that Fate has played on his family and

His dry lips shaped the words, “How much?”

When you see the naked simplicity of that phrase – no artificial guesstimate of what his face might be doing or what particular omens the tone of his voice might carry; no he asked, worriedly, he asked with an anguished grimace, he asked but knew the answer already – and realise that the fussiness of the “silk hat of glossy newness” phrase was not archaic over-writing but a deliberate and mischievous effect, you should recognise why Jacobs’ story endures. The grand illusion of the monkey’s paw is a durable narrative, no doubt, but – especially in the second act, there is close-up magic in the writing.