Posts Tagged ‘frode grytten’

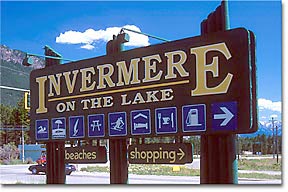

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

Each of the stories in Once You Break A Knuckle features a male protagonist, and Wilson very often examines them within their relationship with other men: fathers and sons, childhood friends, brothers, mentors, employers. Some characters recur at different moments in their lives while others unfold over years within the one story. An example of the latter is Winch, who emerges from the shadow, and initial narrative Point of View, of his father, Conner, in Valley Echo. The father here, as elsewhere in the story cycle, represents at various times – and often simultaneously – an aspirational role model and a booby trap to avoid. Conner and Winch have in common abandonment by Winch’s mother and, when the sixteen year-old Winch develops a crush on a teacher, Miss Hawk, he is disturbed to discover more common ground with his father. Miss Hawk’s presence in this story is typical of the way women feature throughout the collection.  Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

She wore track pants and a windbreaker, had probably been out running – one of those fitness women with legs like nautical rope.

Ray has returned to the area from what seems to have been a self-imposed exile following the breakdown of his relationship with Tracey, who left him for a rival building contractor. Now, with Mud and Alex in support, he begins to consider a new start and a possible relationship with a co-worker, Kelly. The reason for leaving and the reason for staying: the women are irrevocably linked to the emotions the men associate with the town itself.

The machinery of the town is wrought from masculinity. This is best exemplified in the person of John Crease, mounted policeman, security ‘consultant’ in post-war Kosovo, single father, martial artist, a man who, we learn in the opening story, The Elasticity of Bone:

[has] fists…named “Six Months in the Hospital” and “Instant Death”, and he referred to himself as the Kid of Granite, though the last was a bit of humour most people don’t quite get. He wore jeans and a sweatshirt with a picture of two bears in bandanas gnawing human bones. The caption read: Don’t Write Cheques Your Body Can’t Cash.

The description is courtesy of Will, John’s son. Their relationship is claustrophobic, the tenderness expressed in verbal and often physical sparring, and the impression grows across the various stories in which they appear that the bond is built on a stand-off between each man’s occult adherence to his own concept of male-ness. Although his father’s profession beckons, Will is, could be, might become a writer. It’s the time-honoured route out of the small town so much fiction and drama has taken, and which was so wonderfully lampooned by the Monty Python Working-class Playwright sketch (“Aye, ‘ampstead wasn’t good enough for you, was it? … you had to go poncing off to Barnsley, you and yer coal-mining friends.”). Wilson never targets the obvious dramatic flashpoint, never takes a Billy Elliot path by making Will’s writing a fetishised focal point – he just allows the slow resolution to roll into view. When this happens – as with other characters when we catch up with them after encountering their younger selves in earlier stories – the effect is slightly shocking but feels true. This may be because, while the where of these stories is unchanging, the when dances about, evading scrutiny of its larger contemporary narratives and instead presenting the community in moments of temporal suspension: what, in the title story, Will’s loyal friend Mitch describes as “days like these with Will and his dad, looking forward in time or something, just the bullshit of it.” It’s a pretty workable summary of what I mean by real time short stories, and certainly what is a particular trait of short fiction: presenting moments that may be lifted out of the specifics of time and space in their settings but that manage to illuminate something more elemental about the human condition.

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The town lies in the midst of open fields, but beyond the fields are pleasant patches of woodlands. In the wooded places are many little cloistered nooks, quiet places where lovers go to sit on Sunday afternoons.

– but where, in this story, Adventure, Anderson tells of a young woman, Alice, who does not join her contemporaries in the woods but instead –

As she stood looking out over the land something, perhaps the thought of never ceasing life as it expresses itself in the flow of the seasons, fixed her mind on the passing years.

Such is the inevitable fictional loop of the small town narrative, where characters are defined by place, and thereby defined by their bond to or desire to liberate themselves from the “never ceasing life” with its circular dramas and choreographed quirks.

The men in Invermere push and pull one another in various directions but, in the main, they seem scooped up from the same gravel. Difference relates to disorder in a context like this, as in Frode Grytten’s Sing Me To Sleep, where the alienation endured by the middle-aged Smiths fan mounts, through grief at his mother’s long illness and death, and his own quiff-kitemarked loneliness, to a beautiful, baleful crescendo of resolution. In Wilson’s The Mathematics of Friedrich Gauss, the first person narrative builds up a similar momentum, though the emotional surge at the end merely serves to clear away the narrator’s denial and reveal his truth to devastating effect.  Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

The day after we met, on that beach near Saskatoon, my wife showed me how to gather barnacles for protein. She shanked a pocket knife between the rock and the shell and popped the creature off like a coat snap, this grin on her face like nothing could be more fun. I never got the hang of it. She has stopped showing me how.

– We’re not unhappy, I tell my wife.

– Don’t you ever wonder if you could have done better? she says, and she looks at me with eyes grown wide and disappointed.Gauss’s first wife died in 1809, complications from childbirth. A number of people have recounted the scene on her deathbed – how he squandered her final moments, how he spent precious hours preoccupied with a new puzzle in number theory. These tales are all apocryphal. These are the tales of a lonely man. Picture them, Gauss, with his labourer’s shoulders juddering, Johanna in bed with her angel’s hair around her like a skimmer dress, his cheek on the bedside, snub nose grazing her ribs.

It’s one thing to write about the business of being a man with prose that strides into the room, waves its Jeremy Clarkson arse in your face by way of manly humour, and makes a Charlton Heston grab for Chekhov’s gun, placing it in the grip of its cold, dead narrative – but a writer who understands men will be able to depict emotion the way Wilson does in the passage above, and throughout Once You Break A Knuckle. There are versions of being a man here so alien to my sensibilities, Bruce Parry‘s inductions into shamanism in Borneo seem, in comparision, as complicated as setting up a Twitter account. Yet the alchemy at work in D.W. Wilson’s writing is such that, when I think about each of the characters in each of the stories, I can’t help feeling that I have been, at some point in life, some small part of every one of them.

D.W. Wilson‘s Once You Break A Knuckle is published by Bloomsbury Press.