Archive for the ‘Hermetic Spaces’ Category

Review: “Moss Witch and other stories” Sara Maitland (Comma Press, 2013)

Posted on: October 16, 2014

Not simply because it’s been a miserably long time since I last posted here but because of the subject to hand, talking about Sara Maitland’s fusions of science and fiction is truly a long-overdue pleasure. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book of short stories that came across as such a joy to have written. To be frank, the writerly envy Moss Witch and other stories inspires is enough to play merry hell with your entire molecular structure. Having said that, you read a story like A Geological History of Feminism, and you’re very glad that the writer who got to have all this joy was one who can extract from the material a passage of prose as lithe, accomplished and thrillingly quixotic as this:

Not simply because it’s been a miserably long time since I last posted here but because of the subject to hand, talking about Sara Maitland’s fusions of science and fiction is truly a long-overdue pleasure. I don’t think I’ve ever read a book of short stories that came across as such a joy to have written. To be frank, the writerly envy Moss Witch and other stories inspires is enough to play merry hell with your entire molecular structure. Having said that, you read a story like A Geological History of Feminism, and you’re very glad that the writer who got to have all this joy was one who can extract from the material a passage of prose as lithe, accomplished and thrillingly quixotic as this:

And one dawn, so bright that the rising run pushed a shadow-Elsie through the waves and the solid, real Elsie seemed to be chasing it, she had felt a deep surge of energy, more powerful and precise than she had ever felt before. It pushed her up and forward, making her want to sing, to cry out for the beauty and freshness and loveliness of the future. Later, peering down over the charts on the cabin table, she knew what it was. She was sailing over the mid-Atlantic ridge and deep, deep below her, through first blue, then green and down into black water, down below where no one had ever been or could ever go, there was new liquid rock welling up, pouring out, exploding into the cold dark, and crawling east and west either side of the ridge, forming a new, thin dynamic crust, pushing the Americas away from Africa and Europe, changing everything, changing the world. A plate boundary where new rocks are born out of the cauldron below.

This is audacious stuff: the story has Ann, the sole crew member of ‘Elsie’, recounting this journey many years later to her niece Tish, to illuminate how deeply entrenched were the struggles undertaken by the early feminists and to illustrate the resolve they needed to bring about the ground-breaking changes taken for granted today. The image of tectonic plates clashing, oceans breaking and continents shifting is more than a metaphor, though – it’s the real thing, and our involvement in story and character is met in equal measure by a head-spinning tutorial in scientific theory.

Each of Maitland’s stories has come about in consultation with an appropriate scientific expert, ranging across the scientific disciplines to include Earth Scientist Dr Linda Kirstein, consultant for the story quoted above, as well as an ornithologist, an astrophysicist, a mathematician, a stem cell researcher, one of the particle physicists at CERN, and the University of Surrey’s professor of theoretical physics, Jim al-Kalili, who’s famous enough to get to pose for photographs in which he ruminates towards the sunset like he’s a bowl cut short of a Brian Cox. How these dialogues have fed into Maitland’s process is explained in part by an afterword, accompanying each story, by the relevant consultant. So Dr Tara Shears from CERN explains Dirac’s equation – “a simple, far-reaching collection of symbols that led to the prediction of anti-matter” – which is the basis for Maitland’s troubled twins parable, The Beautiful Equation.

Each of Maitland’s stories has come about in consultation with an appropriate scientific expert, ranging across the scientific disciplines to include Earth Scientist Dr Linda Kirstein, consultant for the story quoted above, as well as an ornithologist, an astrophysicist, a mathematician, a stem cell researcher, one of the particle physicists at CERN, and the University of Surrey’s professor of theoretical physics, Jim al-Kalili, who’s famous enough to get to pose for photographs in which he ruminates towards the sunset like he’s a bowl cut short of a Brian Cox. How these dialogues have fed into Maitland’s process is explained in part by an afterword, accompanying each story, by the relevant consultant. So Dr Tara Shears from CERN explains Dirac’s equation – “a simple, far-reaching collection of symbols that led to the prediction of anti-matter” – which is the basis for Maitland’s troubled twins parable, The Beautiful Equation.![]()

In her acknowledgements, Maitland thanks the scientists and muses, “I wish I believed they had as much fun as I did.” It’s easy to characterise the relationship between a writer and a scientist in this sort of collaboration – and it’s one I’ve experienced, with Liverpool University’s Professor of Evolutionary Biology, Greg Hurst and very recently with the robotics pioneer, Francesco Mondada – as resembling that between an adult and a very clever child. Most of the child’s questions are easy enough to answer, but you’re delighted at her fascination with the subject – and every now and then, she’ll come up with a fresh insight that goes beyond the limits of the workaday. It might leave the scientist with a warm glow and a pocketful of inspiration – during our work together on the 2009 Evolving Words project, Greg wrote more poems than anyone else – but the impact on the writer is seismic. If I experienced that within either one of my scientific contexts, imagine something similar but fourteen times over and you get a sense of the excitement surging through Maitland’s writing.

The spectrum of scientific disciplines commandeered for Moss Witch is matched by Maitland’s range of storytelling textures. There are trace elements of Jorge Luis Borges in the willingness to converse with the prehistory of the modern short story. Though there are no explicit pastiches, we brush up against Biblical legend, Greek mythology, Gothic dysmorphia – in the beguiling Double Vision, which had previously surfaced in Comma’s The New Uncanny – and the pitch-dark charm of the title story’s eponymous candidate for a belated place in the Grimm fairy tale canon, where we might expect her to beat the crap out of any bold young princes who dare to come riding by:

The evening came and with it the chill of March air. Venus hung low in the sky, following the sun down behind the hill, and the high white stars came out one by one, visible through the tree branches. She worked all through the darkness. First, she dehydrated the body by stuffing all his orifices with dry sphagnum, more biodegradable than J-cloth and more native than sponge, of which, like all Moss Witches, she kept a regular supply for domestic purposes. It sucked up his body fluids through mouth and ears and anus. She thought too its antiseptic quality might protect her mosses from his contamination after she was gone.

Rumpelstiltskin, we can note, was a rank amateur.

This is as much about the discoverers as the discoveries and another storytelling element is the speculative biography, similar to the approach used by Zoe Lambert for several stories in her The War Tour collection. One example of a story containing a scoop or two from a real life is the heartbreaking – but so beautiful it manages to be uplifting as well – The Mathematics of Magic Carpets, about the ninth century inventor of algebra, Abū‘Abdallāh Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī. Maitland’s writing, whether veering towards myth or folklore, biography or contemporary (and indeed future-facing) short fiction, has the ability to charm and cheer even when there is a dark or sorrowful human story to be told. Science is so often the villain in fiction or at best the well-meaning catalyst for a disastrous future (see the James Franco character in the 2011 film Rise Of The Planet Of The Apes as an example of the latter) but Sara Maitland’s collection speaks with a stirring optimism that has been a major influence on my own recent experiments blending science and short fiction. My consultation with Francesco Mondada has produced The Longhand Option, one of the stories in Comma’s Beta-Life: Stories From An A-life Future, launching shortly in Lancaster and Manchester – more details should appear very soon on this blog.

Ten years ago, the particular context in which the British government chose to make April Fools of its citizens was the war in Iraq. This year, Iraq would seem a very exotic focal point for our denigration when the current government is so busy reducing our domestic certainties – a health service, a welfare state, a justice system – to the status of a blooper reel among the Extras on Michael Gove’s History of Great Britain DVD. When we’re losing track of who we are, of why we even exist as social animals, it is a challenge to contemplate the experience of Iraqis, by whom reality has, during these ten years, been viewed in a perpetual nightmarish REM. Yet Hassan Blasim‘s second collection for Comma Press speaks to our own, particularlised sensations of powerlessness, as much as to the self-evident contexts of war, exile and the way these narratives of suffering become absorbed into a nation’s culture and myths.

Ten years ago, the particular context in which the British government chose to make April Fools of its citizens was the war in Iraq. This year, Iraq would seem a very exotic focal point for our denigration when the current government is so busy reducing our domestic certainties – a health service, a welfare state, a justice system – to the status of a blooper reel among the Extras on Michael Gove’s History of Great Britain DVD. When we’re losing track of who we are, of why we even exist as social animals, it is a challenge to contemplate the experience of Iraqis, by whom reality has, during these ten years, been viewed in a perpetual nightmarish REM. Yet Hassan Blasim‘s second collection for Comma Press speaks to our own, particularlised sensations of powerlessness, as much as to the self-evident contexts of war, exile and the way these narratives of suffering become absorbed into a nation’s culture and myths.

A simple summary of The Iraqi Christ: this is the most urgent writing you will read in short fiction or any other literary format this year. To read these stories is to immerse yourself in tragedy and horror. The imprint of real lives – Blasim’s and those he has encountered – is as evident on the printed page here as lipstick traces on a cigarette, exacerbating the sense of grief that accompanies each story. Blasim’s debut collection for Comma, 2009’s The Madman Of Freedom Square (from which “The Reality and the Record” provided a previous post for this site), was an eloquent, retching cry of disgust; The Iraqi Christ seems to be steeped more in sorrow. And the incredible part is that, from this unimaginable sorrow, what emerges is a savage, unbearable beauty.

The stories portray characters locked in states of fretful, at times lurid, sensory dissonance. If you knew nothing of this book or Blasim’s literary antecedents other than David Eckersall’s cover design, pictured above, you might guess that Franz Kafka sits somewhere in the frame of reference. Short fiction routinely converses with its ghosts and Kafka’s presence is almost that of a recurring character, most conspicuously in The Dung Beetle, an overt reference to Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, with the concerns of the changeling Gregor Samsa, conceived during the First World War, transposed onto those of an Iraqi now residing in Finland, inside a ball of dung. In relating his fictional counterpoint’s story, Blasim makes what I take to be a more direct authorial interjection:

A young Finnish novelist once asked me, with a look of genuine curiosity, ‘How did you read Kafka? Did you read him in Arabic? How could you discover Kafka that way?’ I felt as if I were a suspect in a crime and the Finnish novelist was the detective, and that Kafka was a Western treasure that Ali Baba, the Iraqi, had stolen. In the same way, I might have asked, ‘Did you read Kafka in Finnish?’

Such is the sense of dislocation and depersonalisation, of inurement to brutality and reduction to absurdity, reading Kafka seems less of a choice or privilege than a routine motor function. The Dung Beetle quotes in full Kafka’s Little Fable in which a mouse articulates the essential condition of the Kafkaesque protagonist:

The mouse said, ‘Alas, the world gets smaller every day. It used to be so big that I was frightened. I would run and run, and I was pleased when I finally saw the walls appear on the horizon in every direction, but these long walls run fast to meet each other, and here I am at the end of the room, and in front of me I can see a trap that I must run into.,

‘You only have to change direction,’ said the cat, and tore the mouse up.

The earlier Ali Baba reference directs us to Blasim’s coupling of Kafka with Sheherazade and the One Thousand and One Nights tales, for which the narrative of the young bride using her powers of storytelling to stave off the daily threat of execution is the framing device, an appropriate analogy when claiming asylum.  The deadpan depravity in The Hole exemplifies how these strands become twisted together. The narrator, on the run from masked gunmen as chaos greets the collapse of the government, falls into a hole and encounters a “decrepit old man”, claiming to be a djinni (genie) and calmly carving chunks of flesh to eat from the corpse of a soldier who has previously fallen down the hole. There is no escape and the company only emphasises how divorced this place is from the reality the narrator has known.

The deadpan depravity in The Hole exemplifies how these strands become twisted together. The narrator, on the run from masked gunmen as chaos greets the collapse of the government, falls into a hole and encounters a “decrepit old man”, claiming to be a djinni (genie) and calmly carving chunks of flesh to eat from the corpse of a soldier who has previously fallen down the hole. There is no escape and the company only emphasises how divorced this place is from the reality the narrator has known.

In the 1001 Nights tale of Sinbad’s fourth voyage – several years into his latest enforced sojourn in a land in which he has initially been made to feel welcome and has become happily married – he learns of the bizarre local custom that, when a married man or woman dies, the living spouse is also thrown into the huge pit, that serves as a mass grave, accompanied by the humane provision of a spartan packed lunch for pre-death nourishment. Sinbad’s wife falls ill and dies and, sure enough, both her body and the breathing, protesting form of Sinbad are thrown in the pit. Sinbad survives in his pit of corpses by clubbing any newly-widowed arrival to death with a leg-bone and taking their bread and water for sustenance. These echoes cement Blasim’s storytelling within the traditions of the region but the stories that fuel his writing are timeless and universal, relating to the stark choices facing humans when everything that betokens their humanity has been stripped away. Italo Calvino is another writer cited, via his Mr Palomar character, who painstakingly seeks to quantify the contents of a disparate universe; when ‘Hassan Blasim’ appears as a character, shifting the boundaries of reality in Why Don’t You Write A Novel Instead Of Talking About All These Characters?, there are shades of Paul Auster’s introspections about the nature of truth and story. Where – in, for example, the meta-gumshoe story City Of Glass, itself Edgar Allen Poe’s The Man Of The Crowd by way of, yes, Kafka – Auster will use a character called ‘Paul Auster’ to interrogate the identity of the “I” in whose Point of View the story is being told, it’s couched within the ‘what-if?’ framework we might expect to find in any fictional narrative. Blasim operates from a starting-point in which life has already become that fiction. This is an object lesson for those who assume that it would be enough to transcribe and dust-jacket the extraordinary circumstances of their own lives in order to produce a compelling narrative. Blasim’s life enters Blasim’s fiction as a kind of exorcism: you don’t want to explore how much is actually a record of the truth because you can’t bear to look. In Why Don’t You Write A Novel…?, the narrator makes a prison visit to the man with whom he made the journey to escape Iraq and claim asylum in Europe. Along the way, this companion, Adel Salim, inexplicably murdered a drowning man whom they had met on the refugee trail:

‘Okay, I don’t understand, Adel,’ I said. ‘What were you thinking? Why did you strangle him? What I’m saying may be mad, but why didn’t you let him drown by himself?’

After a short while, he answered hatefully from behind the bars. ‘You’re an arsehole and a fraud. Your name’s Hassan Blasim and you claim to be Salem Hussein. You come here and lecture me. Go fuck yourself, you prick.’

The narrator, aware only of his work as a translator working in the reception centre for asylum seekers, retreats in confusion and struggles to recover memories from before his border crossing. In an encounter on a train, a man, carrying a mouse, identifies him as the author of several stories, including some of those contained in this collection. I don’t know whether Blasim was setting out to articulate this but there’s a particular bleakness to the writing life when you feel you’re holding the weight of all the blood and bones in the world but the only place you have to set it down is something so light and flimsy as the page of a book.

For all the postmodernism and the literary conversations, and the insect and, for Dear Beto, canine narrators, we are taken goosebump-close to what happens in everyday human lives in a protracted war situation, with Jonathan Wright’s translations ensuring no walls remain between these characters and the reader. The Iraqi Christ is eye-catchingly provocative as a title for the book but the story bearing that name provides a more straightforward explanation: it’s a reference to Daniel, an Iraqi soldier who’s a practising Christian and committed gum-chewer so known to his fellow soldiers as the Chewgum Christ, Christ for short. The story, though, we come to realise, is a kind of gospel told by a beyond-the-grave narrator who relates the miraculous, almost unconscious prescience with which this Iraqi Christ manages to evade death, to the point that he takes on a talismanic role among his comrades. A life avoiding death isn’t quite the same as a life, though, and there is sacrifice and redemption to follow in an ending that is built on tragic irony but has a strangely uplifting choreography to it.

For all the postmodernism and the literary conversations, and the insect and, for Dear Beto, canine narrators, we are taken goosebump-close to what happens in everyday human lives in a protracted war situation, with Jonathan Wright’s translations ensuring no walls remain between these characters and the reader. The Iraqi Christ is eye-catchingly provocative as a title for the book but the story bearing that name provides a more straightforward explanation: it’s a reference to Daniel, an Iraqi soldier who’s a practising Christian and committed gum-chewer so known to his fellow soldiers as the Chewgum Christ, Christ for short. The story, though, we come to realise, is a kind of gospel told by a beyond-the-grave narrator who relates the miraculous, almost unconscious prescience with which this Iraqi Christ manages to evade death, to the point that he takes on a talismanic role among his comrades. A life avoiding death isn’t quite the same as a life, though, and there is sacrifice and redemption to follow in an ending that is built on tragic irony but has a strangely uplifting choreography to it.

Further evidence of unexpected uplift comes in the final story, A Thousand and One Knives, a magic realist story of a team of street magicians whose ability to make knives disappear into thin air and then bring them back operates as a twin process of exorcism (again) and healing. The team have found one another through their gifts and rub along as a dysfunctional family group. In an attempt to understand what the trick of disappearing and reappearing knives might mean, the narrator is charged with researching the subject:

It was religious books that I first examined to find references to the trick. Most of the houses in our sector and around had a handful of books and other publications, primarily the Quran, the sayings of the Prophet, stories about Heaven and Hell, and texts about prophets and infidels. It’s true I found many references to knives in these books but they struck me as just laughable. They only had knives for jihad, for treachery, for torture and terror. Swords and blood. Symbols of desert battles and the battles of the future. Victory banners stamped with the name of God, and knives of war.

In the face of this understanding of knives, the group use their skills very little for show and not at all for profit but as a compulsion, like the stories of Sheherazade, because there are things that need to happen, because not doing it is too horrific to contemplate. When we learn of the baby born to the narrator and Souad, the only woman in the group and the only one able to make knives reappear, we see that they have cut themselves into one another’s flesh as well, in acts of transformative love and friendship that – remarkably, by the end of this remarkable collection – allow the reader to emerge with hope still intact, battered, but somehow reinforced.

The Iraqi Christ by Hassan Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright, supported by the English PEN Writers In Translation programme, is published by Comma Press and available in book and e-book form.

It’s a curious business, when the content of a short story anthology is made up of stories in competition with one another. If you haven’t heard the BBC Radio 4 broadcasts of each of the ten shortlisted stories in the annual, BBC/Booktrust-sponsored, increasingly high profile and, for this Olympic year only, International Short Story Award, or if you’ve not yet caught up with the podcasts or got hold of the anthology, stewarded by Comma Press, featuring all ten finalists, you may now be curious as to why the Bulgarian writer, Miroslav Penkov was declared the winner of the £15000 prize. In one sense, the answer is simple to the point of idiocy: the judges got it right. Penkov’s story, East Of The West was the best of the bunch, and the runner-up, Henrietta Rose-Innes’ Sanctuary, was entirely deserving of that recognition. That’s easily declared, but the reasons why you might reach that conclusion, from reading the anthology, are a whole lot more complicated.

It’s a curious business, when the content of a short story anthology is made up of stories in competition with one another. If you haven’t heard the BBC Radio 4 broadcasts of each of the ten shortlisted stories in the annual, BBC/Booktrust-sponsored, increasingly high profile and, for this Olympic year only, International Short Story Award, or if you’ve not yet caught up with the podcasts or got hold of the anthology, stewarded by Comma Press, featuring all ten finalists, you may now be curious as to why the Bulgarian writer, Miroslav Penkov was declared the winner of the £15000 prize. In one sense, the answer is simple to the point of idiocy: the judges got it right. Penkov’s story, East Of The West was the best of the bunch, and the runner-up, Henrietta Rose-Innes’ Sanctuary, was entirely deserving of that recognition. That’s easily declared, but the reasons why you might reach that conclusion, from reading the anthology, are a whole lot more complicated.

To read an anthology compiled in these circumstances at this precise time is to seek to pick out a winner, but once the fifteen grand’s worth of kerfuffle has passed on by, the book remains a short story anthology. Even though no overlying thematic concern has guided the writing of the ten stories; even though, beyond what the selection says about the judges,

the programming of the stories as they appear in the anthology derived from no stronger editorial line than the alphabetical order of the writers’ surnames: still, the stories speak to each other, as in any other collection. Writerly concerns overlap and individual creative decisions coalesce by the accident of their mutual proximity into something that resembles a trend. Emotions, gathered in one place, spill out in another and it becomes hard to work out if the story in front of you can take sole credit for your response. Leave aside all this, and we still have the essential truth about short stories that the best grow in their absence: it’s not when we scrutinise them but in those sudden, private moments when we find that they are scrutinising us, that the power of an individual piece is felt. In such a context, picking a winner should be like punting on raindrops sliding down a windowpane: this one may win, or that one, but all that tells you is that it’s raining outside. There was little to guide us as to the outcome from the previous year’s winner, D.W. Wilson’s The Dead Roads, nor from 2010’s selection by, David Constantine, so it all comes down to the stories themselves. Read as a form guide, the anthology mocks the very process it belongs to, while, read as an anthology, it exceeds its reach.That there are stand-out stories shouldn’t deter anyone from investigating what is going on, thematically and within the writing, in the eight also-reads. Escape plays a persistent role in just about all the stories, the tone set by Lucy Caldwell’s opener, Escape Routes and reinforced by Julian Gough’s The iHole. Escape here – and in the closing story, A Lovely and Terrible Thing by Chris Womersley – is the objective itself, with a destination, or life beyond the moment of release, not a consideration. Caldwell’s Belfast story of the friendship between a young girl and her babysitter, whose ability to connect to the narrator through gaming contrasts with his wider sense of alienation. It articulates a world that’s very close to that of adults but utterly cut off from it as well. The references to gaming and youth depression suggest a nowness to Caldwell’s writing, but Gough’s lovely take on a post-CERN near-future, in which recycling is replaced by the mass production of personal, portable black holes, stands out more clearly as the shortlist’s outstanding depiction of the Way We Live Now. I felt Gough’s pursued the grand narrative arc of his satire too far, and the detail and comedy became too broad, in comparison with a recent Will Self story, iAnna, which makes the comment on technology and contemporary culture while remaining with the characters.

The three stories set in Australia each capture painful hours in the breaking up and holding together of families. M.J. Hyland has a tense father-son rapprochement in Even Pretty Eyes Commit Crimes. Carrie Tiffany depicts a child negotiating a path to a future with an absent father in Before He Left The Family. Womersley balances a supernatural tale, that might almost be lifted from an M.R. James treasury (and evokes Paul Auster’s Mr Vertigo), with a portrait of a father cut off from his family due to his daughter’s medical condition. Each manages to present a reality more convincing than is conveyed by Adam Ross, whose In The Basement uses the device of the extended dinner party anecdote rather more theatrically than I was comfortable with, though it’s equally the type of thing Truman Capote or, again, Auster might have done with the same yarn to spin.

Krys Lee’s The Goose Father has wonderful touches in the slow (but, even allowing for the form, perhaps not quite as slow as the situation demands) epiphany of an austere middle-aged man encountering an unstable but sprite-like young man. This South Korean narrative was the story that gathered me in the most, outside of the top two and the opening half of Gough’s The iHole. Deborah Levy, denied a league and cup double but now freed to concentrate on the Man Booker Prize, lets off the most fireworks in her prose for Black Vodka and, in her narrator, has a character who absolutely commands our attention. It’s adventurous, playful writing but ultimately it’s a sketch of a character that Levy might lend to aspects of future novels. It will also, incidentally, give you a raging thirst for flavoured vodkas.

In the alphabetical sequencing of the anthology, Rose-Innes follows Penkov and dramas viewed from across – and swimming in – rivers feature in both. It’s another example of the emotional chords that can be struck accidentally between stories which each have plenty of their own weight to carry. If there is an arc a reader goes through in reading a short story collection, there might be a science to my being especially receptive to these two stories. So, yes, judging is complex but the most instinctive personal responses have authority in this regard. There are stories that grab hold: Rose-Innes did this with Sanctuary, a family tragedy observed from a series of vantage-points, each one projecting a role onto the narrator of innocent bystander, unwitting voyeur, detective and eventually protector. The detail and intimacy with the land, in this case the South African veldt, has the kind of clarity we’d associate with John Steinbeck, and Rose-Innes would have been my winner had the decision been made on immediate completion of the task of reading all the stories.

In the alphabetical sequencing of the anthology, Rose-Innes follows Penkov and dramas viewed from across – and swimming in – rivers feature in both. It’s another example of the emotional chords that can be struck accidentally between stories which each have plenty of their own weight to carry. If there is an arc a reader goes through in reading a short story collection, there might be a science to my being especially receptive to these two stories. So, yes, judging is complex but the most instinctive personal responses have authority in this regard. There are stories that grab hold: Rose-Innes did this with Sanctuary, a family tragedy observed from a series of vantage-points, each one projecting a role onto the narrator of innocent bystander, unwitting voyeur, detective and eventually protector. The detail and intimacy with the land, in this case the South African veldt, has the kind of clarity we’d associate with John Steinbeck, and Rose-Innes would have been my winner had the decision been made on immediate completion of the task of reading all the stories.

What also happens with stories, though, is this: they won’t let you go. East Of The West hefts the history of a people, the Kosovan war, and twenty years of a love story into what still manages to be a concentrated, complete short story. I mentioned the breaking up and coming together of families in other stories but, here, those moments of crisis are the natural order for a family divided by the width of a river but, in that division, also split into two nations and between prosperity and struggle. Tragedy hovers, ill-defined at first but, over the years, it acquires names and accompanies the narrator, Nose, in his every footstep through adolescence and the plans he has for his adulthood. Penkov gives us a character whose emotions, in the extraordinary circumstances of his life and the history framing it, are utterly real. It’s a credit to the BBC’s award and the good fortune that the Olympic celebration made it eligible that this funny and moving short story will come to wider attention.

What also happens with stories, though, is this: they won’t let you go. East Of The West hefts the history of a people, the Kosovan war, and twenty years of a love story into what still manages to be a concentrated, complete short story. I mentioned the breaking up and coming together of families in other stories but, here, those moments of crisis are the natural order for a family divided by the width of a river but, in that division, also split into two nations and between prosperity and struggle. Tragedy hovers, ill-defined at first but, over the years, it acquires names and accompanies the narrator, Nose, in his every footstep through adolescence and the plans he has for his adulthood. Penkov gives us a character whose emotions, in the extraordinary circumstances of his life and the history framing it, are utterly real. It’s a credit to the BBC’s award and the good fortune that the Olympic celebration made it eligible that this funny and moving short story will come to wider attention.

You go weeks, a couple of months, without blogging about a short story so, when you do, you tell yourself it’s got to be a story that gets you right there, between the ribs. It’s got to be a story that walks the planet like an ambassador for everything you believe about writing. And you know the story you want to use. But it’s not your story, not really. It should be the story that first made you understand, made you believe. But the truth is you had no idea it existed until some guy put you onto it a year ago. You hope they won’t notice. But they’ll notice.

You go weeks, a couple of months, without blogging about a short story so, when you do, you tell yourself it’s got to be a story that gets you right there, between the ribs. It’s got to be a story that walks the planet like an ambassador for everything you believe about writing. And you know the story you want to use. But it’s not your story, not really. It should be the story that first made you understand, made you believe. But the truth is you had no idea it existed until some guy put you onto it a year ago. You hope they won’t notice. But they’ll notice.

So – full disclosure: if this post encourages you to track down Until Gwen, by the writer whose novels, Mystic River and Shutter Island, were made into acclaimed movies, credit must go to my colleague, John Sayle, at Liverpool John Moores University. John introduced the story to first year creative writers in a lecture ostensibly discussing dialogue technique. Certainly, Lehane has a fine ear for the dialogue within Americana’s underbelly, a comfortable fit within a tradition that links Damon Runyan with the likes of Elmore Leonard, Quentin Tarantino and George Pelacanos, joined lately and from a more northerly point by D.W. Wilson. Beyond that, though, the characters come across like you’re watching them in HD after finally jettisoning the old 16″ black & white – you witness them in pungent, raw flesh to the point where it becomes lurid – and Lehane’s dislocated 2nd person narrative propels you into a plot whose most brutal turns are disclosed to you like an opponent’s poker hand.

In quite other ways, and the area I wish to consider here, Until Gwen tells us a story about the writing process that should be instructive to would-be authors grappling with the distinction between having the ideas and making the writing. Dennis Lehane has said that he’d had the opening sentence of Until Gwen long before he had conceived of any of the characters, their relationships or what might happen to them. It’s no wonder, having come up with this line, Lehane knew that someday he’d have to build a story around it:

In quite other ways, and the area I wish to consider here, Until Gwen tells us a story about the writing process that should be instructive to would-be authors grappling with the distinction between having the ideas and making the writing. Dennis Lehane has said that he’d had the opening sentence of Until Gwen long before he had conceived of any of the characters, their relationships or what might happen to them. It’s no wonder, having come up with this line, Lehane knew that someday he’d have to build a story around it:

Your father picks you up from prison in a stolen Dodge Neon, with an 8-ball of coke in the glove compartment and a hooker named Mandy in the back seat.

The one guarantee is that, having read this, your reader is going to move on to the second sentence, which is also pretty good:

Two minutes into the ride, the prison still hanging tilted in the rearview, Mandy tells you that she only hooks part-time.

We must steer the Dodge Neon around any prospective spoilers but there is no jeopardy in noting that, below its carnival transgressive veneer, this opening contains the lead-weighted certainties of the thriller: when even the hooker is only part-time, nothing is quite what it first seems; we may be driving away from the prison, but it’s still there in our wonky eyeline; the orchestrator of the goody bag of petty crime presented to the central character on leaving prison is introduced to us as “Your father”; and even though we, the reader, have all of this shoved onto our lap, we have no idea who our proxy, “you”, is.

Through the remainder of the story, we discover the endgame from the four years’ thinking, forgetting and remembering time afforded to the young man, whom we later discover, as memory returns, was called “Bobby” by his lover, Gwen, conspicuous by her absence from the welcome party mentioned above. The thriller is played out between son and father, while Bobby’s memories of Gwen reveal a further great strength in Lehane’s prose, his facility for articulating male yearning. Gwen is typical of Lehane’s small town, big-hearted women who recognise something approaching nobility in nihilists like Bobby, who in turn represent hope, escape and salvation and whose relationships invariably collapse with the burden of this representation:

You find yourself standing in a Nebraska wheat field. You’re seventeen years old. You learned to drive five years earlier. You were in school once, for two months when you were eight, but you read well and you can multiply three-digit numbers in your head faster than a calculator, and you’ve seen the country with the old man. You’ve learned people aren’t that smart. You’ve learned how to pull lottery-ticket scams and asphalt-paving scams and get free meals with a slight upturn of your brown eyes. You’ve learned that if you hold ten dollars in front of a stranger, he’ll pay twenty to get his hands on it if you play him right. You’ve learned that every good lie is threaded with truth and every accepted truth leaks lies.

You’re seventeen years old in that wheat field. The night breeze smells of wood smoke and feels like dry fingers as it lifts your bangs off your forehead. You remember everything about that night because it is the night you met Gwen. You are two years away from prison, and you feel like someone has finally given you permission to live.

Until Gwen ends the way it does because it began the way it did. Lehane’s premise of bad men and botched heists delivers an operatic crescendo within the short story format. He has written through the ideas sparked by that opening line and, along the way, found this narrative. The methodology enables the characters and situations to take shape amidst a series of tropes with which Lehane is comfortable. The peculiar and deadly sprinkling of diamonds holding the small town in thrall equates to the child murders in Mystic River or the epidemic of stray dogs in Lehane’s long short story, Running Out Of Dog, which also features a woman as potential salvation-figure, as does another short story, Gone Down To Corpus. Meanwhile, Bobby’s quest for his own identity resonates with the story about identity suicide, ICU, for which Paul Auster’s City of Glass is also a touchstone.

All this expansion, from an anonymous beginning to the process whereby the story becomes embedded within the writer’s broader preoccupations, is significant. The story’s performative narrative plays itself out by resolving its central struggle but there is plenty left unresolved, deferring as it does to life’s natural messiness. I’ve seen readers speculate and debate about the morality of the main characters and the fates of those around them but a fascinating titbit about Until Gwen is that Dennis Lehane came away from the story every bit as curious about the characters as his readers were. The characters, he has written, “kept walking around in my head, telling me that we weren’t done yet, that there were more things to say about the entangled currents that made up their bloodlines and their fate.”

The result, the other prompt for which was a challenge to write a theatrical part for his actor brother, which would allow him to play (against type) a morally irredeemable character, was a short play, Coronado. To go into too many details about the additions and alterations made to the story would once more risk spoilers since the play ties up several of the story’s loose ends. It does so with elegance and in a way that suggests Lehane has created a new puzzle for himself with his first act, and resolved it in the second.

The result, the other prompt for which was a challenge to write a theatrical part for his actor brother, which would allow him to play (against type) a morally irredeemable character, was a short play, Coronado. To go into too many details about the additions and alterations made to the story would once more risk spoilers since the play ties up several of the story’s loose ends. It does so with elegance and in a way that suggests Lehane has created a new puzzle for himself with his first act, and resolved it in the second.

Coronado, the script providing the title for a collection otherwise comprising of Lehane’s short stories, stands alone impressively as a play, the strong-arm poetry of the 2nd person narrative in Gwen sculpted to a somewhat less naturalistic set of voices, emphasising perhaps the operatic strains I picked up from the story and very much at home in the American theatre of Arthur Miller or David Mamet. Yet it couldn’t have come about without the ellipses in the short story – had Lehane been fully aware of his characters’ fates, he might not have written the play, might have left them in the short story and that might, perhaps, have become a novel. This makes me wonder about the ethics of leaving matters unexplained. Do we owe our characters (never our readers, who can never be allowed to override our creative controls) answers? For all that they share storylines and sections of text, I am not sure it’s helpful to place Until Gwen and Coronado too close together in our imaginations, lest one text overpowers the other.

An alternative companion piece to Until Gwen might be Vincent Gallo’s brilliant 1998 auteur effort, Buffalo ’66. There are shades of Bobby’s parole disorientation in the opening scenes of Gallo’s petty criminal, newly released from prison with a full bladder and nowhere to relieve it, eventually kidnapping a young tap-dancer (Christina Ricci) in his frustration (although, if Gallo has a fictional role model here, it may be Patrick Dewaere’s superbly jittery shambles Franck, central to a disastrous heist and the most downbeat lovers-on-the-lam scenario imaginable in the 1979 French film Série noire). Whilst a different type of antagonist to the father in the Lehane story, Ben Gazzara’s Jimmy, the father of Gallo’s character, offers a complementary montage of charm and menace.

An alternative companion piece to Until Gwen might be Vincent Gallo’s brilliant 1998 auteur effort, Buffalo ’66. There are shades of Bobby’s parole disorientation in the opening scenes of Gallo’s petty criminal, newly released from prison with a full bladder and nowhere to relieve it, eventually kidnapping a young tap-dancer (Christina Ricci) in his frustration (although, if Gallo has a fictional role model here, it may be Patrick Dewaere’s superbly jittery shambles Franck, central to a disastrous heist and the most downbeat lovers-on-the-lam scenario imaginable in the 1979 French film Série noire). Whilst a different type of antagonist to the father in the Lehane story, Ben Gazzara’s Jimmy, the father of Gallo’s character, offers a complementary montage of charm and menace.

Julian Barnes, in a recent Guardian article, ahead of the reissue of Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End, for which he has written the introduction, discusses how Ford’s quartet of novels has come to be regarded as a tetralogy, with the final novel, Last Post, widely derided and commonly discarded. Indeed, save for a motif of a couple of logs of cedar wood thrown on the fire, Tom Stoppard’s acclaimed adaptation of Ford’s novels for BBC/HBO, which prompted the re-print, brings the parade to an end at the climax of book three. Barnes makes a persuasive case for Last Post but, in doing so, relates Graham Greene’s decision to dispose of the volume in an edition he edited in the 1960s. Greene accused the final book of clearing up the earlier volumes’ “valuable ambiguities.” I find Coronado a soulful re-imagining of Until Gwen, the more fascinating because the author has, in a way, re-interpreted his own work. But Greene’s phrase reminds us that ambiguity is a defining strength of the short story. Whether Lehane had done anything else with them or not, the success of his and many other short stories is that the characters might step out from the text, valuable ambiguities intact, and wander around the reader’s minds for years to come, insisting that we aren’t done yet.

“Would you please please please please please please please stop

talking?”

I’m going to take heed of what she asks here in the sense that I will attempt to talk about Ernest Hemingway’s 1927 story Hills Like White Elephants without including any spoilers about what the man and the woman are talking about.

I say this in full recognition that taking such precautions for anyone coming to a short story blog to read about a story analysed on probably every Creative Writing university degree course in the English-speaking world, brings to mind the time two women walked into a charity second-hand shop I was in last summer: “Ooh, look, Mum,” said one, pointing over to the music section, “Queen’s Greatest Hits!” I thought, how can that be exciting? There are people who care about music and some of them like Queen; then there are people who don’t care about music, and Queen have them covered too. If you like Queen, then surely to God you’ve had time and opportunity in your life to get hold of their Greatest Hits? Similarly, if you know anything about Hills Like White Elephants, reason would suggest that the undisclosed but “awfully simple”, “perfectly natural”, “perfectly simple” procedure under discussion, omerta may no longer be a requirement.

Nevertheless, I will steer around the matter simply because, having used it in creative writing teaching with undergraduates, I’ve seen that an isolated reading produces a range of interpretations as to the subtext of the central conversation. This, of course, means that two people will have the same words before them yet be reading two completely different stories. We might suppose that the strategy in storytelling is to have the reader understand what that story is. Of course, you may wish to leave certain matters open to conjecture and debate – what explains this behaviour? is the narrator as reliable as s/he would like us to believe? what happens next? – but you don’t expect the plot summary to be a multiple choice.

Nevertheless, I will steer around the matter simply because, having used it in creative writing teaching with undergraduates, I’ve seen that an isolated reading produces a range of interpretations as to the subtext of the central conversation. This, of course, means that two people will have the same words before them yet be reading two completely different stories. We might suppose that the strategy in storytelling is to have the reader understand what that story is. Of course, you may wish to leave certain matters open to conjecture and debate – what explains this behaviour? is the narrator as reliable as s/he would like us to believe? what happens next? – but you don’t expect the plot summary to be a multiple choice.

Actually, I don’t believe there is great room for dispute about Hemingway’s plot here: close attention to the emotional ebb and flow of the conversation shows it not to be a blur of Dadaist abstraction in the least, and further observation of the landscape either side of the railway bar, in which the two travelling Americans drink beer and Anis while waiting for their connecting train to Madrid, should dissolve any mystery. However, the very fact that the sparsity of more definitive signposts leads some readers to very different interpretations tells us a great deal about the remarkable quality of Hemingway’s writing here, working in the 3rd person objective voice he could very well have patented.

We are with these two people for just shy of three quarters of an hour and all we have of them is everything they say. Our reading is therefore a real time activity. We respond as we would if observing and eavesdropping random people in our normal lives. In this way, we can see how the café setting (as, despite the beer and the fire water, we’re entitled to think of it, this being mainland Europe) is fundamental to the authenticity of the couple’s conversational iceberg. Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard’s dabbed handkerchief in the Milford station café in Brief Encounter is a good indicator of the sort of protocol into which we’re entering in this environment: a place of non-belonging, in a pocket of restricted time, anonymous but under scrutiny of all those around who have nothing to do but wait and watch, the limits to which emotions can be expressed and truths can be articulated are all too apparent. In the case of the Madrid-bound Americans, there is the additional context that they are locked, together, within a de facto exile’s experience. The place they are in now is not a home, nor a home from home, nor even a destination. The type of relaxation available in the Central Perk model of Third Space establishments – a social space that can intersect with the work sphere; a public space in which to express a suitably modulated private identity – cannot be attempted here. Instead, we have enforced camaraderie and a mutual illiteracy when it comes to reading one another’s signals:

The place they are in now is not a home, nor a home from home, nor even a destination. The type of relaxation available in the Central Perk model of Third Space establishments – a social space that can intersect with the work sphere; a public space in which to express a suitably modulated private identity – cannot be attempted here. Instead, we have enforced camaraderie and a mutual illiteracy when it comes to reading one another’s signals:

The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the

felt pads and the beer glasses on the table and looked at the man and the

girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun

and the country was brown and dry.

“They look like white elephants,” she said.

“I’ve never seen one,” the man drank his beer.

“No, you wouldn’t have.”

“I might have,” the man said. “Just because you say I wouldn’t have

doesn’t prove anything.”

The talk replaces thoughts or one’s talk tramples on the other’s thoughts; in this, they occupy a similar space to Zoe Lambert’s squabbling interrailers in two of her stories in The War Tour. They drink together and the setting gives them a place to do this but those of us who can eavesdrop in both English and Spanish (and, by the magic of Hemingway’s decision to use English when Spanish is spoken, this means all of us) recognise that there are barriers and dependency issues there, as he has to do the talking for both of them:

The woman came out through the curtains with two glasses of beer and

put them down on the damp felt pads. “The train comes in five minutes,” she

said.

“What did she say?” asked the girl.

“That the train is coming in five minutes.”

The girl smiled brightly at the woman, to thank her.

Earlier, Hemingway jump-cuts through the sequence in which the man orders beer and then Anis del Toro and the woman brings the drinks over. He leaves in everything that’s said. Everything else that happens is silence, just as every conversation on every restaurant first date, or during every long-term couple’s rare bout of face time, is suspended when there is a member of the waiting staff hovering over the table. The couple’s conversation is not guarded because they are busy constructing a rabbit warren of metaphors and codes. They talk like this, in the situation they are in, because so would you. And when she strafes him with pleases to get him to stop talking, a nugget of dialogue that, out of context, seems stylised to the point of absurdity, can actually be appreciated as the one moment of unstoppable emotional honesty in the entire scene.

The conversation will pick up again, though, on the train, and then along the Gran Via or wherever they are headed. There is no obvious epiphany for the couple in Hills Like White Elephants. As we polish off the anis we’ve been sure we’ve been drinking, and set to hauling the luggage we just know has been sitting at our feet, the epiphany – that we’ve been drawn entirely into the scene as fellow customers – belongs to us.

The conversation will pick up again, though, on the train, and then along the Gran Via or wherever they are headed. There is no obvious epiphany for the couple in Hills Like White Elephants. As we polish off the anis we’ve been sure we’ve been drinking, and set to hauling the luggage we just know has been sitting at our feet, the epiphany – that we’ve been drawn entirely into the scene as fellow customers – belongs to us.

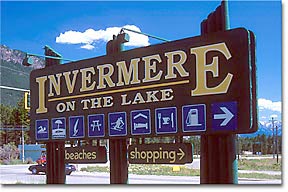

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

Each of the stories in Once You Break A Knuckle features a male protagonist, and Wilson very often examines them within their relationship with other men: fathers and sons, childhood friends, brothers, mentors, employers. Some characters recur at different moments in their lives while others unfold over years within the one story. An example of the latter is Winch, who emerges from the shadow, and initial narrative Point of View, of his father, Conner, in Valley Echo. The father here, as elsewhere in the story cycle, represents at various times – and often simultaneously – an aspirational role model and a booby trap to avoid. Conner and Winch have in common abandonment by Winch’s mother and, when the sixteen year-old Winch develops a crush on a teacher, Miss Hawk, he is disturbed to discover more common ground with his father. Miss Hawk’s presence in this story is typical of the way women feature throughout the collection.  Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

She wore track pants and a windbreaker, had probably been out running – one of those fitness women with legs like nautical rope.

Ray has returned to the area from what seems to have been a self-imposed exile following the breakdown of his relationship with Tracey, who left him for a rival building contractor. Now, with Mud and Alex in support, he begins to consider a new start and a possible relationship with a co-worker, Kelly. The reason for leaving and the reason for staying: the women are irrevocably linked to the emotions the men associate with the town itself.

The machinery of the town is wrought from masculinity. This is best exemplified in the person of John Crease, mounted policeman, security ‘consultant’ in post-war Kosovo, single father, martial artist, a man who, we learn in the opening story, The Elasticity of Bone:

[has] fists…named “Six Months in the Hospital” and “Instant Death”, and he referred to himself as the Kid of Granite, though the last was a bit of humour most people don’t quite get. He wore jeans and a sweatshirt with a picture of two bears in bandanas gnawing human bones. The caption read: Don’t Write Cheques Your Body Can’t Cash.

The description is courtesy of Will, John’s son. Their relationship is claustrophobic, the tenderness expressed in verbal and often physical sparring, and the impression grows across the various stories in which they appear that the bond is built on a stand-off between each man’s occult adherence to his own concept of male-ness. Although his father’s profession beckons, Will is, could be, might become a writer. It’s the time-honoured route out of the small town so much fiction and drama has taken, and which was so wonderfully lampooned by the Monty Python Working-class Playwright sketch (“Aye, ‘ampstead wasn’t good enough for you, was it? … you had to go poncing off to Barnsley, you and yer coal-mining friends.”). Wilson never targets the obvious dramatic flashpoint, never takes a Billy Elliot path by making Will’s writing a fetishised focal point – he just allows the slow resolution to roll into view. When this happens – as with other characters when we catch up with them after encountering their younger selves in earlier stories – the effect is slightly shocking but feels true. This may be because, while the where of these stories is unchanging, the when dances about, evading scrutiny of its larger contemporary narratives and instead presenting the community in moments of temporal suspension: what, in the title story, Will’s loyal friend Mitch describes as “days like these with Will and his dad, looking forward in time or something, just the bullshit of it.” It’s a pretty workable summary of what I mean by real time short stories, and certainly what is a particular trait of short fiction: presenting moments that may be lifted out of the specifics of time and space in their settings but that manage to illuminate something more elemental about the human condition.

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The town lies in the midst of open fields, but beyond the fields are pleasant patches of woodlands. In the wooded places are many little cloistered nooks, quiet places where lovers go to sit on Sunday afternoons.

– but where, in this story, Adventure, Anderson tells of a young woman, Alice, who does not join her contemporaries in the woods but instead –

As she stood looking out over the land something, perhaps the thought of never ceasing life as it expresses itself in the flow of the seasons, fixed her mind on the passing years.

Such is the inevitable fictional loop of the small town narrative, where characters are defined by place, and thereby defined by their bond to or desire to liberate themselves from the “never ceasing life” with its circular dramas and choreographed quirks.

The men in Invermere push and pull one another in various directions but, in the main, they seem scooped up from the same gravel. Difference relates to disorder in a context like this, as in Frode Grytten’s Sing Me To Sleep, where the alienation endured by the middle-aged Smiths fan mounts, through grief at his mother’s long illness and death, and his own quiff-kitemarked loneliness, to a beautiful, baleful crescendo of resolution. In Wilson’s The Mathematics of Friedrich Gauss, the first person narrative builds up a similar momentum, though the emotional surge at the end merely serves to clear away the narrator’s denial and reveal his truth to devastating effect.  Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

The day after we met, on that beach near Saskatoon, my wife showed me how to gather barnacles for protein. She shanked a pocket knife between the rock and the shell and popped the creature off like a coat snap, this grin on her face like nothing could be more fun. I never got the hang of it. She has stopped showing me how.

– We’re not unhappy, I tell my wife.

– Don’t you ever wonder if you could have done better? she says, and she looks at me with eyes grown wide and disappointed.Gauss’s first wife died in 1809, complications from childbirth. A number of people have recounted the scene on her deathbed – how he squandered her final moments, how he spent precious hours preoccupied with a new puzzle in number theory. These tales are all apocryphal. These are the tales of a lonely man. Picture them, Gauss, with his labourer’s shoulders juddering, Johanna in bed with her angel’s hair around her like a skimmer dress, his cheek on the bedside, snub nose grazing her ribs.

It’s one thing to write about the business of being a man with prose that strides into the room, waves its Jeremy Clarkson arse in your face by way of manly humour, and makes a Charlton Heston grab for Chekhov’s gun, placing it in the grip of its cold, dead narrative – but a writer who understands men will be able to depict emotion the way Wilson does in the passage above, and throughout Once You Break A Knuckle. There are versions of being a man here so alien to my sensibilities, Bruce Parry‘s inductions into shamanism in Borneo seem, in comparision, as complicated as setting up a Twitter account. Yet the alchemy at work in D.W. Wilson’s writing is such that, when I think about each of the characters in each of the stories, I can’t help feeling that I have been, at some point in life, some small part of every one of them.

D.W. Wilson‘s Once You Break A Knuckle is published by Bloomsbury Press.

Zoe Lambert’s debut collection, The War Tour, places horror and banality in uncomfortable proximity. The title suggests this: if we are not the direct participants or, for the sake of greater moral comfort, the victims in warfare, how do we stand in relation to the horror? As tourists, turning the bloodshed into a photo opportunity? As writers, notebooks and dictaphones poised so we might appropriate the voices of those who were actually there? The book is not designed to offer a settling response to this queasy feeling that we are somehow implicated in the actions that shape Lambert’s narratives.

Zoe Lambert’s debut collection, The War Tour, places horror and banality in uncomfortable proximity. The title suggests this: if we are not the direct participants or, for the sake of greater moral comfort, the victims in warfare, how do we stand in relation to the horror? As tourists, turning the bloodshed into a photo opportunity? As writers, notebooks and dictaphones poised so we might appropriate the voices of those who were actually there? The book is not designed to offer a settling response to this queasy feeling that we are somehow implicated in the actions that shape Lambert’s narratives.

In her opening story, These Words are No More Than a Story About a Woman on a Bus, Lambert deploys the second person narrative voice – “you” – to place the reader inside the crawling skin of a suited, briefcase-wielding commuter latched onto by an elderly Lithuanian woman, keen to share her memories of her country’s invasion by the Russian army. “You’re not sure what to do with this story,” the narrative tells you. It’s a pertinent observation. The woman’s story does not belong to us – none of these stories does – so what is going on when we take possession of them? Lambert acknowledges that her literary ventriloquism could be interpreted as an unwarranted, even imperialist, intervention. The collection ends with a chapter of Notes, in which Lambert responds to (her own, as much as anyone else’s) concerns that her approach risks being seen in terms of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak‘s objection to the well-meaning idea of “speaking for” the disempowered. The Notes then snake away from the theoretical question to give an illuminating picture of Lambert’s poetics. She considers the notion of appropriating the voices of historical figures by considering the diaries of the imperialist Captain John Hanning Speke and the botanist Charlotte Manning. The diaries serve as fictions – not everything is told or understood by their writers; they remain versions within which Lambert weaves her own imaginings as a writer, experiencing the process as a profound collaboration. If appropriation is taking place, that’s because that’s what writers do. I’ll do it to you if we ever met, and I do it to myself every time I write.

I do, however, find truth in Spivak’s point when reading a story like Road Song, by Joanne Harris, which appears in a 2010 Vintage collection, Because I Am A Girl, for which seven renowned authors spoke to young girls in different continents in order to represent their stories and situations. The proceeds from the collection support the charity, Plan, which aims to support self-empowerment in the developing world so the stories can be accepted as an elegant stump for a worthy cause. However, in a passage like this, set in her character Adjo’s local market, I find the prose Harris constructs less of a vehicle for the young girl’s cultural experience and more a giddy, exotic rickshaw ride for a tourist sensibility:

Adjo likes the market. There are so many things to see there. Young men riding mopeds; women riding pillion. Sellers of manioc and fried plantain. Flatbed trucks bearing timber. Vaudou men selling spells and charms. Dough-ball stands by the roadside. Pancakes and foufou; yams and bananas; mountains of millet and peppers and rice. Fabrics of all colours; sarongs and scarves and dupattas. Bead necklaces, bronze earrings; tins of harissa; bangles; pottery dishes; bottles and gourds; spices and salt; garlands of chillies; cooking pots; brooms; baskets; plastic buckets; knives; Coca-Cola; engine oil and sandals made from plaited grass.

Lambert is not concerned with the thrilling wordiness of her diverse subjects: she is concerned with character. What bothers her, as a short story obsessive, is the problem of collapsing War – that emesis of human struggle, conflict, which shatters life in half a second and hangs onto lives for years and through generations; that pitches your street against mine in the next block along and then follows us across oceans and sets itself up in a new continent – into the tidy sealed boxes we call stories. The collection takes its cue from Trotsky’s assertion that “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.” Though there was a point when I was wondering how many more ways Lambert could find to write the sudden explosion or hail of gunfire that seemed to arrive like a narrative epiphany in a succession of the stories, the collection as a whole examines war – and shows how war examines us – from many more angles than just direct armed conflict.

The characters, conflicts and locations manouevre around one another in the stories. Two stories cross paths on Manchester’s Langworthy Road: in From Kandahar, squaddie Phil returns from a tour of duty, decorated but unable to reconcile his hero’s status with the knowledge he has acquired; in We’ll Meet Again, Rwandan care home assistant Leon leads an ordinary life yet it is one consistently shadowed by genocide. As a Manchester writer, the setting and therefore the stories are available to Lambert; she also allows the reader to detect an autobiographical veracity in the snapshots of the squabbling interrailing couple, Yvonne and James, traipsing around central Europe’s ancient and recent war zones in the title story and Our Backs To The Fort. If Lambert’s city and travel history have Hitchcockian cameos in these stories, it is the level of research, the desire to bring to light hidden, forgotten or sidelined stories of war, and the willingness to showcase her writerly concerns that form the basis of Lambert’s personal hallmark.

The characters, conflicts and locations manouevre around one another in the stories. Two stories cross paths on Manchester’s Langworthy Road: in From Kandahar, squaddie Phil returns from a tour of duty, decorated but unable to reconcile his hero’s status with the knowledge he has acquired; in We’ll Meet Again, Rwandan care home assistant Leon leads an ordinary life yet it is one consistently shadowed by genocide. As a Manchester writer, the setting and therefore the stories are available to Lambert; she also allows the reader to detect an autobiographical veracity in the snapshots of the squabbling interrailing couple, Yvonne and James, traipsing around central Europe’s ancient and recent war zones in the title story and Our Backs To The Fort. If Lambert’s city and travel history have Hitchcockian cameos in these stories, it is the level of research, the desire to bring to light hidden, forgotten or sidelined stories of war, and the willingness to showcase her writerly concerns that form the basis of Lambert’s personal hallmark.

The effect can be polemic. There is, in 33 Bullets a welcome if shaming illustration of the conditions in which failed asylum seekers are detained in Britain, and the intractable barriers they face during the appeals process. This would not work if the characters were ciphers for a political argument. As it is, the central character of 33 Bullets, Devrim, is one of the most compelling in the book, an academic of insufficient standing to be considered at risk should he be returned to Iran, desperate to finish and publish a study of the Kurdish poet, Ahmed Arif, in order to demonstrate his credentials:

No-one understood that if his work was accepted by a journal, he might get a book contract, and when he was recognised as an authority on Kurdish literature he might get special dispensation to stay in the UK. ‘With this,’ he said, holding up his work, ‘they won’t deport me!’

Japhet [his cellmate] frowned. ‘Deport,’ he said. ‘They deport you…me… ‘ He gestured around the room. ‘Tout le monde. Est-ce que vous comprendez?’

Ultimately, Devrim finds a purpose in his futile paper-chase, influenced by Japhet’s steely pragmatism. There is a conversation between Arif’s words and Devrim’s attempts to write about them (“Poems are necessary to survival. We all make them out of the words we have.“) and there is a conversation between the words already written and the words Lambert is trying to find to map and make sense of these experiences. It’s a bold writer who works in full acceptance of the inevitable failure of her project, but failure in this case is also the most honorable and necessary response: to completely understand the workings of people’s minds in wartime would demand from us madness or monstrosity. We encounter Japhet again in When The Truck Came, a tense and powerful rites of passage from the schoolboy stumbling into and then through the ranks of a militia to being one of the personal bodyguards of the unit’s leader,’The General’, a figure who will, from this week on, inevitably bring to mind Joseph Kony. Here’s where the gap with full understanding comes in, though. What we now know of Kony exceeds even the sickening demonstrations of nihilism to which Japhet is privy, just as, in From Kandahar, Phil’s existential turbulence couldn’t compete for horror with the latest news of British casualties in Afghanistan. War is interested in you, but it’s more interested in excising the pus from its own scabs, using a rusty nail, than with attending to your emotional bruises. And Lambert is attempting to take on neither Andy McNabb nor Sun Tzu here: as the collection progresses, the observation of how a writer finds points of contact and communication with her subjects becomes increasingly engrossing.

Some of Lambert’s characters offer easy skins into which a contemporary British writer may slip: both Senka, the Serbian narrator of Turbofolk, and Phil, disembarking the bus on Langworthy Road, are every prodigal child returning home after growing to adulthood elsewhere, and having to deal with overbearing relations and hometown ghosts. Without experience of the Balkan conflict, we still can recognise Senka’s response to her mother’s anxiety over the post-war recriminations directed at journalists seen as having supported genocide – journalists like Senka’s seriously ill father:

Some of Lambert’s characters offer easy skins into which a contemporary British writer may slip: both Senka, the Serbian narrator of Turbofolk, and Phil, disembarking the bus on Langworthy Road, are every prodigal child returning home after growing to adulthood elsewhere, and having to deal with overbearing relations and hometown ghosts. Without experience of the Balkan conflict, we still can recognise Senka’s response to her mother’s anxiety over the post-war recriminations directed at journalists seen as having supported genocide – journalists like Senka’s seriously ill father:

I really want to lie down, drink some beer, check my email. But I sigh and pick up the print out of the article: ‘Media Warmongers Should Face Prosecution at the ICTY.’