Posts Tagged ‘small town’

You go weeks, a couple of months, without blogging about a short story so, when you do, you tell yourself it’s got to be a story that gets you right there, between the ribs. It’s got to be a story that walks the planet like an ambassador for everything you believe about writing. And you know the story you want to use. But it’s not your story, not really. It should be the story that first made you understand, made you believe. But the truth is you had no idea it existed until some guy put you onto it a year ago. You hope they won’t notice. But they’ll notice.

You go weeks, a couple of months, without blogging about a short story so, when you do, you tell yourself it’s got to be a story that gets you right there, between the ribs. It’s got to be a story that walks the planet like an ambassador for everything you believe about writing. And you know the story you want to use. But it’s not your story, not really. It should be the story that first made you understand, made you believe. But the truth is you had no idea it existed until some guy put you onto it a year ago. You hope they won’t notice. But they’ll notice.

So – full disclosure: if this post encourages you to track down Until Gwen, by the writer whose novels, Mystic River and Shutter Island, were made into acclaimed movies, credit must go to my colleague, John Sayle, at Liverpool John Moores University. John introduced the story to first year creative writers in a lecture ostensibly discussing dialogue technique. Certainly, Lehane has a fine ear for the dialogue within Americana’s underbelly, a comfortable fit within a tradition that links Damon Runyan with the likes of Elmore Leonard, Quentin Tarantino and George Pelacanos, joined lately and from a more northerly point by D.W. Wilson. Beyond that, though, the characters come across like you’re watching them in HD after finally jettisoning the old 16″ black & white – you witness them in pungent, raw flesh to the point where it becomes lurid – and Lehane’s dislocated 2nd person narrative propels you into a plot whose most brutal turns are disclosed to you like an opponent’s poker hand.

In quite other ways, and the area I wish to consider here, Until Gwen tells us a story about the writing process that should be instructive to would-be authors grappling with the distinction between having the ideas and making the writing. Dennis Lehane has said that he’d had the opening sentence of Until Gwen long before he had conceived of any of the characters, their relationships or what might happen to them. It’s no wonder, having come up with this line, Lehane knew that someday he’d have to build a story around it:

In quite other ways, and the area I wish to consider here, Until Gwen tells us a story about the writing process that should be instructive to would-be authors grappling with the distinction between having the ideas and making the writing. Dennis Lehane has said that he’d had the opening sentence of Until Gwen long before he had conceived of any of the characters, their relationships or what might happen to them. It’s no wonder, having come up with this line, Lehane knew that someday he’d have to build a story around it:

Your father picks you up from prison in a stolen Dodge Neon, with an 8-ball of coke in the glove compartment and a hooker named Mandy in the back seat.

The one guarantee is that, having read this, your reader is going to move on to the second sentence, which is also pretty good:

Two minutes into the ride, the prison still hanging tilted in the rearview, Mandy tells you that she only hooks part-time.

We must steer the Dodge Neon around any prospective spoilers but there is no jeopardy in noting that, below its carnival transgressive veneer, this opening contains the lead-weighted certainties of the thriller: when even the hooker is only part-time, nothing is quite what it first seems; we may be driving away from the prison, but it’s still there in our wonky eyeline; the orchestrator of the goody bag of petty crime presented to the central character on leaving prison is introduced to us as “Your father”; and even though we, the reader, have all of this shoved onto our lap, we have no idea who our proxy, “you”, is.

Through the remainder of the story, we discover the endgame from the four years’ thinking, forgetting and remembering time afforded to the young man, whom we later discover, as memory returns, was called “Bobby” by his lover, Gwen, conspicuous by her absence from the welcome party mentioned above. The thriller is played out between son and father, while Bobby’s memories of Gwen reveal a further great strength in Lehane’s prose, his facility for articulating male yearning. Gwen is typical of Lehane’s small town, big-hearted women who recognise something approaching nobility in nihilists like Bobby, who in turn represent hope, escape and salvation and whose relationships invariably collapse with the burden of this representation:

You find yourself standing in a Nebraska wheat field. You’re seventeen years old. You learned to drive five years earlier. You were in school once, for two months when you were eight, but you read well and you can multiply three-digit numbers in your head faster than a calculator, and you’ve seen the country with the old man. You’ve learned people aren’t that smart. You’ve learned how to pull lottery-ticket scams and asphalt-paving scams and get free meals with a slight upturn of your brown eyes. You’ve learned that if you hold ten dollars in front of a stranger, he’ll pay twenty to get his hands on it if you play him right. You’ve learned that every good lie is threaded with truth and every accepted truth leaks lies.

You’re seventeen years old in that wheat field. The night breeze smells of wood smoke and feels like dry fingers as it lifts your bangs off your forehead. You remember everything about that night because it is the night you met Gwen. You are two years away from prison, and you feel like someone has finally given you permission to live.

Until Gwen ends the way it does because it began the way it did. Lehane’s premise of bad men and botched heists delivers an operatic crescendo within the short story format. He has written through the ideas sparked by that opening line and, along the way, found this narrative. The methodology enables the characters and situations to take shape amidst a series of tropes with which Lehane is comfortable. The peculiar and deadly sprinkling of diamonds holding the small town in thrall equates to the child murders in Mystic River or the epidemic of stray dogs in Lehane’s long short story, Running Out Of Dog, which also features a woman as potential salvation-figure, as does another short story, Gone Down To Corpus. Meanwhile, Bobby’s quest for his own identity resonates with the story about identity suicide, ICU, for which Paul Auster’s City of Glass is also a touchstone.

All this expansion, from an anonymous beginning to the process whereby the story becomes embedded within the writer’s broader preoccupations, is significant. The story’s performative narrative plays itself out by resolving its central struggle but there is plenty left unresolved, deferring as it does to life’s natural messiness. I’ve seen readers speculate and debate about the morality of the main characters and the fates of those around them but a fascinating titbit about Until Gwen is that Dennis Lehane came away from the story every bit as curious about the characters as his readers were. The characters, he has written, “kept walking around in my head, telling me that we weren’t done yet, that there were more things to say about the entangled currents that made up their bloodlines and their fate.”

The result, the other prompt for which was a challenge to write a theatrical part for his actor brother, which would allow him to play (against type) a morally irredeemable character, was a short play, Coronado. To go into too many details about the additions and alterations made to the story would once more risk spoilers since the play ties up several of the story’s loose ends. It does so with elegance and in a way that suggests Lehane has created a new puzzle for himself with his first act, and resolved it in the second.

The result, the other prompt for which was a challenge to write a theatrical part for his actor brother, which would allow him to play (against type) a morally irredeemable character, was a short play, Coronado. To go into too many details about the additions and alterations made to the story would once more risk spoilers since the play ties up several of the story’s loose ends. It does so with elegance and in a way that suggests Lehane has created a new puzzle for himself with his first act, and resolved it in the second.

Coronado, the script providing the title for a collection otherwise comprising of Lehane’s short stories, stands alone impressively as a play, the strong-arm poetry of the 2nd person narrative in Gwen sculpted to a somewhat less naturalistic set of voices, emphasising perhaps the operatic strains I picked up from the story and very much at home in the American theatre of Arthur Miller or David Mamet. Yet it couldn’t have come about without the ellipses in the short story – had Lehane been fully aware of his characters’ fates, he might not have written the play, might have left them in the short story and that might, perhaps, have become a novel. This makes me wonder about the ethics of leaving matters unexplained. Do we owe our characters (never our readers, who can never be allowed to override our creative controls) answers? For all that they share storylines and sections of text, I am not sure it’s helpful to place Until Gwen and Coronado too close together in our imaginations, lest one text overpowers the other.

An alternative companion piece to Until Gwen might be Vincent Gallo’s brilliant 1998 auteur effort, Buffalo ’66. There are shades of Bobby’s parole disorientation in the opening scenes of Gallo’s petty criminal, newly released from prison with a full bladder and nowhere to relieve it, eventually kidnapping a young tap-dancer (Christina Ricci) in his frustration (although, if Gallo has a fictional role model here, it may be Patrick Dewaere’s superbly jittery shambles Franck, central to a disastrous heist and the most downbeat lovers-on-the-lam scenario imaginable in the 1979 French film Série noire). Whilst a different type of antagonist to the father in the Lehane story, Ben Gazzara’s Jimmy, the father of Gallo’s character, offers a complementary montage of charm and menace.

An alternative companion piece to Until Gwen might be Vincent Gallo’s brilliant 1998 auteur effort, Buffalo ’66. There are shades of Bobby’s parole disorientation in the opening scenes of Gallo’s petty criminal, newly released from prison with a full bladder and nowhere to relieve it, eventually kidnapping a young tap-dancer (Christina Ricci) in his frustration (although, if Gallo has a fictional role model here, it may be Patrick Dewaere’s superbly jittery shambles Franck, central to a disastrous heist and the most downbeat lovers-on-the-lam scenario imaginable in the 1979 French film Série noire). Whilst a different type of antagonist to the father in the Lehane story, Ben Gazzara’s Jimmy, the father of Gallo’s character, offers a complementary montage of charm and menace.

Julian Barnes, in a recent Guardian article, ahead of the reissue of Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End, for which he has written the introduction, discusses how Ford’s quartet of novels has come to be regarded as a tetralogy, with the final novel, Last Post, widely derided and commonly discarded. Indeed, save for a motif of a couple of logs of cedar wood thrown on the fire, Tom Stoppard’s acclaimed adaptation of Ford’s novels for BBC/HBO, which prompted the re-print, brings the parade to an end at the climax of book three. Barnes makes a persuasive case for Last Post but, in doing so, relates Graham Greene’s decision to dispose of the volume in an edition he edited in the 1960s. Greene accused the final book of clearing up the earlier volumes’ “valuable ambiguities.” I find Coronado a soulful re-imagining of Until Gwen, the more fascinating because the author has, in a way, re-interpreted his own work. But Greene’s phrase reminds us that ambiguity is a defining strength of the short story. Whether Lehane had done anything else with them or not, the success of his and many other short stories is that the characters might step out from the text, valuable ambiguities intact, and wander around the reader’s minds for years to come, insisting that we aren’t done yet.

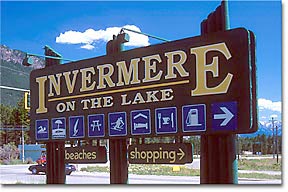

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

Each of the stories in Once You Break A Knuckle features a male protagonist, and Wilson very often examines them within their relationship with other men: fathers and sons, childhood friends, brothers, mentors, employers. Some characters recur at different moments in their lives while others unfold over years within the one story. An example of the latter is Winch, who emerges from the shadow, and initial narrative Point of View, of his father, Conner, in Valley Echo. The father here, as elsewhere in the story cycle, represents at various times – and often simultaneously – an aspirational role model and a booby trap to avoid. Conner and Winch have in common abandonment by Winch’s mother and, when the sixteen year-old Winch develops a crush on a teacher, Miss Hawk, he is disturbed to discover more common ground with his father. Miss Hawk’s presence in this story is typical of the way women feature throughout the collection.  Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

She wore track pants and a windbreaker, had probably been out running – one of those fitness women with legs like nautical rope.

Ray has returned to the area from what seems to have been a self-imposed exile following the breakdown of his relationship with Tracey, who left him for a rival building contractor. Now, with Mud and Alex in support, he begins to consider a new start and a possible relationship with a co-worker, Kelly. The reason for leaving and the reason for staying: the women are irrevocably linked to the emotions the men associate with the town itself.

The machinery of the town is wrought from masculinity. This is best exemplified in the person of John Crease, mounted policeman, security ‘consultant’ in post-war Kosovo, single father, martial artist, a man who, we learn in the opening story, The Elasticity of Bone:

[has] fists…named “Six Months in the Hospital” and “Instant Death”, and he referred to himself as the Kid of Granite, though the last was a bit of humour most people don’t quite get. He wore jeans and a sweatshirt with a picture of two bears in bandanas gnawing human bones. The caption read: Don’t Write Cheques Your Body Can’t Cash.

The description is courtesy of Will, John’s son. Their relationship is claustrophobic, the tenderness expressed in verbal and often physical sparring, and the impression grows across the various stories in which they appear that the bond is built on a stand-off between each man’s occult adherence to his own concept of male-ness. Although his father’s profession beckons, Will is, could be, might become a writer. It’s the time-honoured route out of the small town so much fiction and drama has taken, and which was so wonderfully lampooned by the Monty Python Working-class Playwright sketch (“Aye, ‘ampstead wasn’t good enough for you, was it? … you had to go poncing off to Barnsley, you and yer coal-mining friends.”). Wilson never targets the obvious dramatic flashpoint, never takes a Billy Elliot path by making Will’s writing a fetishised focal point – he just allows the slow resolution to roll into view. When this happens – as with other characters when we catch up with them after encountering their younger selves in earlier stories – the effect is slightly shocking but feels true. This may be because, while the where of these stories is unchanging, the when dances about, evading scrutiny of its larger contemporary narratives and instead presenting the community in moments of temporal suspension: what, in the title story, Will’s loyal friend Mitch describes as “days like these with Will and his dad, looking forward in time or something, just the bullshit of it.” It’s a pretty workable summary of what I mean by real time short stories, and certainly what is a particular trait of short fiction: presenting moments that may be lifted out of the specifics of time and space in their settings but that manage to illuminate something more elemental about the human condition.

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The town lies in the midst of open fields, but beyond the fields are pleasant patches of woodlands. In the wooded places are many little cloistered nooks, quiet places where lovers go to sit on Sunday afternoons.

– but where, in this story, Adventure, Anderson tells of a young woman, Alice, who does not join her contemporaries in the woods but instead –

As she stood looking out over the land something, perhaps the thought of never ceasing life as it expresses itself in the flow of the seasons, fixed her mind on the passing years.

Such is the inevitable fictional loop of the small town narrative, where characters are defined by place, and thereby defined by their bond to or desire to liberate themselves from the “never ceasing life” with its circular dramas and choreographed quirks.

The men in Invermere push and pull one another in various directions but, in the main, they seem scooped up from the same gravel. Difference relates to disorder in a context like this, as in Frode Grytten’s Sing Me To Sleep, where the alienation endured by the middle-aged Smiths fan mounts, through grief at his mother’s long illness and death, and his own quiff-kitemarked loneliness, to a beautiful, baleful crescendo of resolution. In Wilson’s The Mathematics of Friedrich Gauss, the first person narrative builds up a similar momentum, though the emotional surge at the end merely serves to clear away the narrator’s denial and reveal his truth to devastating effect.  Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

The day after we met, on that beach near Saskatoon, my wife showed me how to gather barnacles for protein. She shanked a pocket knife between the rock and the shell and popped the creature off like a coat snap, this grin on her face like nothing could be more fun. I never got the hang of it. She has stopped showing me how.

– We’re not unhappy, I tell my wife.

– Don’t you ever wonder if you could have done better? she says, and she looks at me with eyes grown wide and disappointed.Gauss’s first wife died in 1809, complications from childbirth. A number of people have recounted the scene on her deathbed – how he squandered her final moments, how he spent precious hours preoccupied with a new puzzle in number theory. These tales are all apocryphal. These are the tales of a lonely man. Picture them, Gauss, with his labourer’s shoulders juddering, Johanna in bed with her angel’s hair around her like a skimmer dress, his cheek on the bedside, snub nose grazing her ribs.

It’s one thing to write about the business of being a man with prose that strides into the room, waves its Jeremy Clarkson arse in your face by way of manly humour, and makes a Charlton Heston grab for Chekhov’s gun, placing it in the grip of its cold, dead narrative – but a writer who understands men will be able to depict emotion the way Wilson does in the passage above, and throughout Once You Break A Knuckle. There are versions of being a man here so alien to my sensibilities, Bruce Parry‘s inductions into shamanism in Borneo seem, in comparision, as complicated as setting up a Twitter account. Yet the alchemy at work in D.W. Wilson’s writing is such that, when I think about each of the characters in each of the stories, I can’t help feeling that I have been, at some point in life, some small part of every one of them.

D.W. Wilson‘s Once You Break A Knuckle is published by Bloomsbury Press.