Posts Tagged ‘bbc national short story award 2011’

It’s a curious business, when the content of a short story anthology is made up of stories in competition with one another. If you haven’t heard the BBC Radio 4 broadcasts of each of the ten shortlisted stories in the annual, BBC/Booktrust-sponsored, increasingly high profile and, for this Olympic year only, International Short Story Award, or if you’ve not yet caught up with the podcasts or got hold of the anthology, stewarded by Comma Press, featuring all ten finalists, you may now be curious as to why the Bulgarian writer, Miroslav Penkov was declared the winner of the £15000 prize. In one sense, the answer is simple to the point of idiocy: the judges got it right. Penkov’s story, East Of The West was the best of the bunch, and the runner-up, Henrietta Rose-Innes’ Sanctuary, was entirely deserving of that recognition. That’s easily declared, but the reasons why you might reach that conclusion, from reading the anthology, are a whole lot more complicated.

It’s a curious business, when the content of a short story anthology is made up of stories in competition with one another. If you haven’t heard the BBC Radio 4 broadcasts of each of the ten shortlisted stories in the annual, BBC/Booktrust-sponsored, increasingly high profile and, for this Olympic year only, International Short Story Award, or if you’ve not yet caught up with the podcasts or got hold of the anthology, stewarded by Comma Press, featuring all ten finalists, you may now be curious as to why the Bulgarian writer, Miroslav Penkov was declared the winner of the £15000 prize. In one sense, the answer is simple to the point of idiocy: the judges got it right. Penkov’s story, East Of The West was the best of the bunch, and the runner-up, Henrietta Rose-Innes’ Sanctuary, was entirely deserving of that recognition. That’s easily declared, but the reasons why you might reach that conclusion, from reading the anthology, are a whole lot more complicated.

To read an anthology compiled in these circumstances at this precise time is to seek to pick out a winner, but once the fifteen grand’s worth of kerfuffle has passed on by, the book remains a short story anthology. Even though no overlying thematic concern has guided the writing of the ten stories; even though, beyond what the selection says about the judges,

the programming of the stories as they appear in the anthology derived from no stronger editorial line than the alphabetical order of the writers’ surnames: still, the stories speak to each other, as in any other collection. Writerly concerns overlap and individual creative decisions coalesce by the accident of their mutual proximity into something that resembles a trend. Emotions, gathered in one place, spill out in another and it becomes hard to work out if the story in front of you can take sole credit for your response. Leave aside all this, and we still have the essential truth about short stories that the best grow in their absence: it’s not when we scrutinise them but in those sudden, private moments when we find that they are scrutinising us, that the power of an individual piece is felt. In such a context, picking a winner should be like punting on raindrops sliding down a windowpane: this one may win, or that one, but all that tells you is that it’s raining outside. There was little to guide us as to the outcome from the previous year’s winner, D.W. Wilson’s The Dead Roads, nor from 2010’s selection by, David Constantine, so it all comes down to the stories themselves. Read as a form guide, the anthology mocks the very process it belongs to, while, read as an anthology, it exceeds its reach.That there are stand-out stories shouldn’t deter anyone from investigating what is going on, thematically and within the writing, in the eight also-reads. Escape plays a persistent role in just about all the stories, the tone set by Lucy Caldwell’s opener, Escape Routes and reinforced by Julian Gough’s The iHole. Escape here – and in the closing story, A Lovely and Terrible Thing by Chris Womersley – is the objective itself, with a destination, or life beyond the moment of release, not a consideration. Caldwell’s Belfast story of the friendship between a young girl and her babysitter, whose ability to connect to the narrator through gaming contrasts with his wider sense of alienation. It articulates a world that’s very close to that of adults but utterly cut off from it as well. The references to gaming and youth depression suggest a nowness to Caldwell’s writing, but Gough’s lovely take on a post-CERN near-future, in which recycling is replaced by the mass production of personal, portable black holes, stands out more clearly as the shortlist’s outstanding depiction of the Way We Live Now. I felt Gough’s pursued the grand narrative arc of his satire too far, and the detail and comedy became too broad, in comparison with a recent Will Self story, iAnna, which makes the comment on technology and contemporary culture while remaining with the characters.

The three stories set in Australia each capture painful hours in the breaking up and holding together of families. M.J. Hyland has a tense father-son rapprochement in Even Pretty Eyes Commit Crimes. Carrie Tiffany depicts a child negotiating a path to a future with an absent father in Before He Left The Family. Womersley balances a supernatural tale, that might almost be lifted from an M.R. James treasury (and evokes Paul Auster’s Mr Vertigo), with a portrait of a father cut off from his family due to his daughter’s medical condition. Each manages to present a reality more convincing than is conveyed by Adam Ross, whose In The Basement uses the device of the extended dinner party anecdote rather more theatrically than I was comfortable with, though it’s equally the type of thing Truman Capote or, again, Auster might have done with the same yarn to spin.

Krys Lee’s The Goose Father has wonderful touches in the slow (but, even allowing for the form, perhaps not quite as slow as the situation demands) epiphany of an austere middle-aged man encountering an unstable but sprite-like young man. This South Korean narrative was the story that gathered me in the most, outside of the top two and the opening half of Gough’s The iHole. Deborah Levy, denied a league and cup double but now freed to concentrate on the Man Booker Prize, lets off the most fireworks in her prose for Black Vodka and, in her narrator, has a character who absolutely commands our attention. It’s adventurous, playful writing but ultimately it’s a sketch of a character that Levy might lend to aspects of future novels. It will also, incidentally, give you a raging thirst for flavoured vodkas.

In the alphabetical sequencing of the anthology, Rose-Innes follows Penkov and dramas viewed from across – and swimming in – rivers feature in both. It’s another example of the emotional chords that can be struck accidentally between stories which each have plenty of their own weight to carry. If there is an arc a reader goes through in reading a short story collection, there might be a science to my being especially receptive to these two stories. So, yes, judging is complex but the most instinctive personal responses have authority in this regard. There are stories that grab hold: Rose-Innes did this with Sanctuary, a family tragedy observed from a series of vantage-points, each one projecting a role onto the narrator of innocent bystander, unwitting voyeur, detective and eventually protector. The detail and intimacy with the land, in this case the South African veldt, has the kind of clarity we’d associate with John Steinbeck, and Rose-Innes would have been my winner had the decision been made on immediate completion of the task of reading all the stories.

In the alphabetical sequencing of the anthology, Rose-Innes follows Penkov and dramas viewed from across – and swimming in – rivers feature in both. It’s another example of the emotional chords that can be struck accidentally between stories which each have plenty of their own weight to carry. If there is an arc a reader goes through in reading a short story collection, there might be a science to my being especially receptive to these two stories. So, yes, judging is complex but the most instinctive personal responses have authority in this regard. There are stories that grab hold: Rose-Innes did this with Sanctuary, a family tragedy observed from a series of vantage-points, each one projecting a role onto the narrator of innocent bystander, unwitting voyeur, detective and eventually protector. The detail and intimacy with the land, in this case the South African veldt, has the kind of clarity we’d associate with John Steinbeck, and Rose-Innes would have been my winner had the decision been made on immediate completion of the task of reading all the stories.

What also happens with stories, though, is this: they won’t let you go. East Of The West hefts the history of a people, the Kosovan war, and twenty years of a love story into what still manages to be a concentrated, complete short story. I mentioned the breaking up and coming together of families in other stories but, here, those moments of crisis are the natural order for a family divided by the width of a river but, in that division, also split into two nations and between prosperity and struggle. Tragedy hovers, ill-defined at first but, over the years, it acquires names and accompanies the narrator, Nose, in his every footstep through adolescence and the plans he has for his adulthood. Penkov gives us a character whose emotions, in the extraordinary circumstances of his life and the history framing it, are utterly real. It’s a credit to the BBC’s award and the good fortune that the Olympic celebration made it eligible that this funny and moving short story will come to wider attention.

What also happens with stories, though, is this: they won’t let you go. East Of The West hefts the history of a people, the Kosovan war, and twenty years of a love story into what still manages to be a concentrated, complete short story. I mentioned the breaking up and coming together of families in other stories but, here, those moments of crisis are the natural order for a family divided by the width of a river but, in that division, also split into two nations and between prosperity and struggle. Tragedy hovers, ill-defined at first but, over the years, it acquires names and accompanies the narrator, Nose, in his every footstep through adolescence and the plans he has for his adulthood. Penkov gives us a character whose emotions, in the extraordinary circumstances of his life and the history framing it, are utterly real. It’s a credit to the BBC’s award and the good fortune that the Olympic celebration made it eligible that this funny and moving short story will come to wider attention.

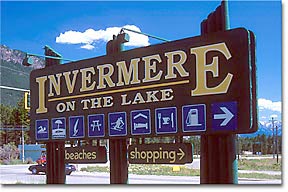

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

There is currently no indication in the Wikipedia entry on Invermere, British Columbia, a destination for summer retreats held like a slingshot by the Rocky Mountains around Windermere Lake, of the town’s literary significance. We may not be operating on the level of pilgrimages to addresses on Baker Street or for dérives through Dublin, but the small Canadian town has made an emphatic claim to a place on the short fiction map. The backdrop to D.W Wilson’s 2011 BBC National Short Story Award-winner, The Dead Roads, which I looked at back in October and which is included here, is examined in closer detail throughout Wilson’s debut collection. Invermere, the town out from which The Dead Road‘s protagonists are taking a road trip, is a constant presence throughout. The primary subject matter, though, is less the town, more its menfolk.

Each of the stories in Once You Break A Knuckle features a male protagonist, and Wilson very often examines them within their relationship with other men: fathers and sons, childhood friends, brothers, mentors, employers. Some characters recur at different moments in their lives while others unfold over years within the one story. An example of the latter is Winch, who emerges from the shadow, and initial narrative Point of View, of his father, Conner, in Valley Echo. The father here, as elsewhere in the story cycle, represents at various times – and often simultaneously – an aspirational role model and a booby trap to avoid. Conner and Winch have in common abandonment by Winch’s mother and, when the sixteen year-old Winch develops a crush on a teacher, Miss Hawk, he is disturbed to discover more common ground with his father. Miss Hawk’s presence in this story is typical of the way women feature throughout the collection.  Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

Neither irrelevant nor invisble, Invermere’s women represent additional spurs and challenges to the men, occasional comforts and somewhat baffling certainty alongside the other constants of their lives, like the trucks, the beer, the frozen lake, the condominiums in construction and the slippage of time. This is perhaps articulated most clearly in The Persistence, where women are central to the gaze of the protagonist, Ray, as can be seen in the memorable economy of this description of Alex, the attractive wife of Ray’s friend and current employer, Mud:

She wore track pants and a windbreaker, had probably been out running – one of those fitness women with legs like nautical rope.

Ray has returned to the area from what seems to have been a self-imposed exile following the breakdown of his relationship with Tracey, who left him for a rival building contractor. Now, with Mud and Alex in support, he begins to consider a new start and a possible relationship with a co-worker, Kelly. The reason for leaving and the reason for staying: the women are irrevocably linked to the emotions the men associate with the town itself.

The machinery of the town is wrought from masculinity. This is best exemplified in the person of John Crease, mounted policeman, security ‘consultant’ in post-war Kosovo, single father, martial artist, a man who, we learn in the opening story, The Elasticity of Bone:

[has] fists…named “Six Months in the Hospital” and “Instant Death”, and he referred to himself as the Kid of Granite, though the last was a bit of humour most people don’t quite get. He wore jeans and a sweatshirt with a picture of two bears in bandanas gnawing human bones. The caption read: Don’t Write Cheques Your Body Can’t Cash.

The description is courtesy of Will, John’s son. Their relationship is claustrophobic, the tenderness expressed in verbal and often physical sparring, and the impression grows across the various stories in which they appear that the bond is built on a stand-off between each man’s occult adherence to his own concept of male-ness. Although his father’s profession beckons, Will is, could be, might become a writer. It’s the time-honoured route out of the small town so much fiction and drama has taken, and which was so wonderfully lampooned by the Monty Python Working-class Playwright sketch (“Aye, ‘ampstead wasn’t good enough for you, was it? … you had to go poncing off to Barnsley, you and yer coal-mining friends.”). Wilson never targets the obvious dramatic flashpoint, never takes a Billy Elliot path by making Will’s writing a fetishised focal point – he just allows the slow resolution to roll into view. When this happens – as with other characters when we catch up with them after encountering their younger selves in earlier stories – the effect is slightly shocking but feels true. This may be because, while the where of these stories is unchanging, the when dances about, evading scrutiny of its larger contemporary narratives and instead presenting the community in moments of temporal suspension: what, in the title story, Will’s loyal friend Mitch describes as “days like these with Will and his dad, looking forward in time or something, just the bullshit of it.” It’s a pretty workable summary of what I mean by real time short stories, and certainly what is a particular trait of short fiction: presenting moments that may be lifted out of the specifics of time and space in their settings but that manage to illuminate something more elemental about the human condition.

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The small town location provides the grammar for this story cycle. We’ve seen how other contemporary writers have pursued unifying themes for their short story collections – Hassan Blasim and Zoe Lambert‘s variations on war; Anthony Doerr‘s employment of memory as a framing device – but this thematic approach, while it offers publishers of single author collections the selling point of a hook, that makes it very much suited to our times, has a formidable history. With his story cycle based around one location, Wilson is making a connection with James Joyce’s The Dubliners or, more specifically in the small town context, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio where –

The town lies in the midst of open fields, but beyond the fields are pleasant patches of woodlands. In the wooded places are many little cloistered nooks, quiet places where lovers go to sit on Sunday afternoons.

– but where, in this story, Adventure, Anderson tells of a young woman, Alice, who does not join her contemporaries in the woods but instead –

As she stood looking out over the land something, perhaps the thought of never ceasing life as it expresses itself in the flow of the seasons, fixed her mind on the passing years.

Such is the inevitable fictional loop of the small town narrative, where characters are defined by place, and thereby defined by their bond to or desire to liberate themselves from the “never ceasing life” with its circular dramas and choreographed quirks.

The men in Invermere push and pull one another in various directions but, in the main, they seem scooped up from the same gravel. Difference relates to disorder in a context like this, as in Frode Grytten’s Sing Me To Sleep, where the alienation endured by the middle-aged Smiths fan mounts, through grief at his mother’s long illness and death, and his own quiff-kitemarked loneliness, to a beautiful, baleful crescendo of resolution. In Wilson’s The Mathematics of Friedrich Gauss, the first person narrative builds up a similar momentum, though the emotional surge at the end merely serves to clear away the narrator’s denial and reveal his truth to devastating effect.  Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

Along the way, we learn about the narrator’s inability, as the local mathematics teacher, to live up to the physical expectations of the manually proficient locals – such as his eminently capable wife – and we learn of his project, writing a biography of Carl Friedrich Gauss, the inventor of the heliotrope, who managed to combine mathematical genius with a labourer’s physicality:

The day after we met, on that beach near Saskatoon, my wife showed me how to gather barnacles for protein. She shanked a pocket knife between the rock and the shell and popped the creature off like a coat snap, this grin on her face like nothing could be more fun. I never got the hang of it. She has stopped showing me how.

– We’re not unhappy, I tell my wife.

– Don’t you ever wonder if you could have done better? she says, and she looks at me with eyes grown wide and disappointed.Gauss’s first wife died in 1809, complications from childbirth. A number of people have recounted the scene on her deathbed – how he squandered her final moments, how he spent precious hours preoccupied with a new puzzle in number theory. These tales are all apocryphal. These are the tales of a lonely man. Picture them, Gauss, with his labourer’s shoulders juddering, Johanna in bed with her angel’s hair around her like a skimmer dress, his cheek on the bedside, snub nose grazing her ribs.

It’s one thing to write about the business of being a man with prose that strides into the room, waves its Jeremy Clarkson arse in your face by way of manly humour, and makes a Charlton Heston grab for Chekhov’s gun, placing it in the grip of its cold, dead narrative – but a writer who understands men will be able to depict emotion the way Wilson does in the passage above, and throughout Once You Break A Knuckle. There are versions of being a man here so alien to my sensibilities, Bruce Parry‘s inductions into shamanism in Borneo seem, in comparision, as complicated as setting up a Twitter account. Yet the alchemy at work in D.W. Wilson’s writing is such that, when I think about each of the characters in each of the stories, I can’t help feeling that I have been, at some point in life, some small part of every one of them.

D.W. Wilson‘s Once You Break A Knuckle is published by Bloomsbury Press.

The afternoon was spent preparing for a lecture on John Steinbeck’s Breakfast. Solidarity; the dignity of labour; Steinbeck’s prose always working up from the land and the people, coming back always to the land and the people; the synapses of the American Left passing this ideal via Steinbeck from the Wobblies and Joe Hill to Woody Guthrie, and on to Bob Dylan, to Gil Scott-Heron, to Angela Davis, to John Sayle, to Michael Moore. Stepping out of this aesthetic into D.W. Wilson‘s 2011 BBC National Short Story Prize-winning The Dead Roads felt a brutal re-entry into the nihilistic realpolitik of 21st century getting high and getting by.

The afternoon was spent preparing for a lecture on John Steinbeck’s Breakfast. Solidarity; the dignity of labour; Steinbeck’s prose always working up from the land and the people, coming back always to the land and the people; the synapses of the American Left passing this ideal via Steinbeck from the Wobblies and Joe Hill to Woody Guthrie, and on to Bob Dylan, to Gil Scott-Heron, to Angela Davis, to John Sayle, to Michael Moore. Stepping out of this aesthetic into D.W. Wilson‘s 2011 BBC National Short Story Prize-winning The Dead Roads felt a brutal re-entry into the nihilistic realpolitik of 21st century getting high and getting by.

Animal had a way of not caring too much and a way of hitting on Vic. He was twenty-six and hunted looking, with engine-grease stubble and red eyes sunk past his cheekbones. In his commie hat and Converses he had that hurting lurch, like a scrapper’s swag, dragging foot after foot with his knees loose and his shoulders slumped. He’d drink a garden hose under the table if it looked at him wrong. He once boned a girl in some poison ivy bushes, but was a gentleman about it. An ugly dent caved his forehead and rumours around Invermere said he’d been booted by a cow and then survived.

The retina-grabbing intensity in this description of Animal Brooks – road trip companion to the narrator, Dunc, and Dunc’s sometime girlfriend Vic – is somewhat hard-boiled and somewhat in the transgressive vein of a Hubert Selby Jr or Chuck Palahniuk. It’s an impression that barely makes it into the second paragraph, though, as the three companions head across the Canadian Rocky Mountains, towards the Northern Lights, and it becomes clear that it’s the emotions stirred up by their adventures, rather than the adventures themselves, that will define this story.

The difficulty, and danger, with analysing a prizewinning story is that you could grab hold of it with the trembling, clenched fist of the struggling writer and view it in terms of: “So this is the style and subject matter my prose has to sleep with if I want it to win any prizes.” Alternatively, there’s the news media reading of the story, which will focus on the money that one writer has won, and the names of the slightly better known writers that were passed over by the judges.  It was a syndrome that found perfect expression recently when the Nobel Prize for Literature went, not to Bob Dylan, nor even the likes of Thomas Pynchon or Les Murray, but to Tomas Tranströmer. I compared the deflated response of headline writers – expecting a Dylan v Keats Revisited pseudbath – to that of the papers ten years ago when a Premier League footballer revealed to have had an extramarital affair, having hitherto been masked by privacy laws with speculation growing, was revealed not to be an international superstar but the journeyman midfielder and Blackburn Rovers captain, Garry Flitcroft. The Sun‘s banner headline – “IT’S GARRY FLITCROFT” – was an Ozymandian masterpiece.

It was a syndrome that found perfect expression recently when the Nobel Prize for Literature went, not to Bob Dylan, nor even the likes of Thomas Pynchon or Les Murray, but to Tomas Tranströmer. I compared the deflated response of headline writers – expecting a Dylan v Keats Revisited pseudbath – to that of the papers ten years ago when a Premier League footballer revealed to have had an extramarital affair, having hitherto been masked by privacy laws with speculation growing, was revealed not to be an international superstar but the journeyman midfielder and Blackburn Rovers captain, Garry Flitcroft. The Sun‘s banner headline – “IT’S GARRY FLITCROFT” – was an Ozymandian masterpiece.

It’s the way Wilson gets the machine of the story to work that makes The Dead Roads a significant new presence in our short story universe. The story is told with the benefit of hindsight – it’s set in 2002 and the potentially fatal dramatic high point, that turns out to be merely chastening, is flagged up in the breezy opening sentence – but it’s withheld from us what that benefit provides. By the end, Dunc appears suspended in a moment we know has gone by. He’s arrived at what seems a resolution regarding his relationship with Animal, the archetypal small town childhood friend you never grow up fast enough to get away from, and thereby his passing into adulthood; particularly definitive is his awareness of how he feels about Vic, who seems to slip like mercury between the gazes of all the men in the story. Yet there’s no sense of to what, beyond this moment, any of this has led. We just know that, on a mountaintop, Dunc has acquired a vantage point on his life he may never attain again.

Wilson prods the themes along with each new disclosure of character among the three road trippers, and Walla, the Native who acts as a mirror to the group and a plot catalyst for the story. If our initial impression of Animal was of a thuggish creature of base instinct, egregious in his overt pursuit of Vic, Wilson provides him with stepping stones towards a greater complexity:

He’d packed nothing but his wallet and a bottle-rimmed copy of The Once and Future King, and he threatened to beat me to death with the Camaro’s dipstick if he caught me touching his book. His brother used to read it to him before bed, and that made it an item of certain value, a real point of civic pride.

The role of the T.H. White re-telling of the Arthurian legend seems to reach beyond Animal’s protection of it as an emblem of family comforts. We later see him struggle through it, “finger under each sentence”, and for all its painstaking nature, his attachment to the book is a notable contrast with the more intelligent but infuriatingly passive Dunc, who senses he should have been able to accompany Vic to university but instead has ceded that side of Vic to the man purse carrier, just as he seems to be ceding her raw, pleasure-seeking side to Animal. Vic clearly seems to be a Guinevere in this equation but Wilson avoids too easy and crass signposting of plot parallels with White’s epic.

The role of the T.H. White re-telling of the Arthurian legend seems to reach beyond Animal’s protection of it as an emblem of family comforts. We later see him struggle through it, “finger under each sentence”, and for all its painstaking nature, his attachment to the book is a notable contrast with the more intelligent but infuriatingly passive Dunc, who senses he should have been able to accompany Vic to university but instead has ceded that side of Vic to the man purse carrier, just as he seems to be ceding her raw, pleasure-seeking side to Animal. Vic clearly seems to be a Guinevere in this equation but Wilson avoids too easy and crass signposting of plot parallels with White’s epic.

For all the Arthurian overtones, for all that it steers away from the transgressive towards something nearer the dirty realism of Tobias Wolff, for all the Hemingwayesque nada of the competitive posturing pit where men try to show that they are men, for all, indeed, that the shadow of Steinbeck doesn’t entirely depart over the course of a reading, a story lives and dies in the quality of its sentences. In Animal’s reaction when Walla points out that he’s just put diesel in a petrol tank, we can see how this story, about seeing things the way they actually are, will stay with us when we’ve forgotten how we came across it in the first place:

Animal stared straight at the Native guy, as if in a game of chicken instead of wrecking his engine with the wrong fuel, as if he just needed to overcome something besides the way things actually were, as if he could just be stubborn enough.