Archive for the ‘The writer’ Category

The transition from medical marvel to sick man on a recovery ward takes a couple of sets of doors, half a corridor and a few seconds. Even the erstwhile wonder at the speed of my recovery is giving way to solicitation about the remaining breathing and immunological issues that are holding up the rate of my recovery. Time – all time – is flexible in here. The only minutes that are certain are those resembling a George Saunders dialogue, spacing apart the hours like lifebuoys.

Yes, a cup of tea please.

Yes, I will have breakfast. Coffee and bran flakes please.

Yes, I’ll have paracetamol.

Yes please. Cup of tea.

Yes I have. Yes they did open.

Much of this could have been predicted, once we’ve brushed past my failure to predict any of this. I’d never picked up before on the stockings, though. Ted stockings might sound like the support your feet and calves need to prepare you to sit through a long, smug presentation by an ideas-guy with a face mic, but they exemplify my institutionalisation. When I had barely returned to consciousness, I raged against the stockings, white knee-length, muscle-stranglers that made me resemble a Regency dandy, albeit one wearing robot feet. The feet snapped every few seconds, pushing my shins, ankles and toes in random directions. Later, when the (entirely necessary) tin leg-breakers had been removed, the stockings remained in place, a monumental, ever-present itch. Any offer I’d have to be relieved of them for a short while would be accepted gratefully. Some days they’d forget to put them back on and I’d fantasise about a consultant standing above me, telling me they’re ready for me to lose the stockings.

The other night, though, I noticed how puffy my bare feet were, and how cold they were in the bed, and I asked a nurse to put them back on. I think that might be a signal for a shift in how the blog’s going to progress because, in all fairness, that was a really boring story.

But I hope it’s fair to say it’s one I needed to tell.

Banal Fabulous

Posted on: November 19, 2014

I thought I’d use the previous post to give you a break from the gloopy pornography of my hospital stay, where my CT Scan from the other week is being passed around the surgical fraternity like a link to the John Merrick Flickr account. In all honesty, though, coma, intubation and paralysis do tend to promote solipsism. For all the moments of high drama, the propensity for massive danger or hope to arrive in a second; for all the emotional churn, the life resolutions, the love that’s been communicated not least via comments on this blog (for which my thanks are expressed briefly and generally but meant personally and fully); for all the scarification, hallucination and weird science, these two weeks have been overwhelmingly about waiting.

Now I’m on the recovery ward – the last bed before a potential temporary discharge until I’m pre-opped again to fix the thing they reckon I’ve spent my life adapting to so well it both delayed and guaranteed the implosion a fortnight ago – the blur of momentary sleep and wakeful dreaming is no longer a factor. Nevertheless, each day continues to be a glacial pursuit of banal triumphs.

The poetry is in the banal. Sometimes I feel like Primo Levi; sometimes it’s more like being on a long-haul flight. I spend days fixating on how to get this tube removed or downgraded – when it happens, there’s a moment of relief then I start to be irritated by another attachment I’d accepted previously. I crave taste and flavour when I’m nil by mouth then a week of banal hospital cake helps food lose its emotional heft.

It’s because the pace of life is necessarily slow, the distance between a positive decision and the

liberating action stretches like pizza dough and when holes start to appear, it can be easy to fall through them. Endurance and tolerance, Solomon Northrup rather than Grundy, are absolutely necessary but there’s a risk of atrophy in that too.

And then something happens.

This afternoon, Sally removed my remaining drains. I can now walk without having to negotiate the help of a nurse to disentangle my tubes and carry my bottles. All I’m connected to, for the time being, is oxygen. The bureaucracy of this situation just lost a layer of paperwork.

I’m still trying to tap these pieces out on my phone with one thumb so academic veracity is frankly a bit of a busk but when we talk about the birth of the modern short story, we go back to Poe and we go back to Chekhov, primarily because there we find the transition from the short tale as a succinct abridgement of the larger narrative to a specialised examination of the way life moves. The journey from one moment to the next.

Poe’s time passed by each moment creeping up on the last, magnifying unease and shrouded in trips and traps. Chekhov could see the passage of time in the way one moment withered away to form the next. The ultimate examination of withering time is Gusev, drawn from his own experience of a ship’s sick bay. There is a closing sequence, which once resembled a leap from realism to imagination but now I’m not so sure, in which Gusev, who has spent the story pinned to the ground in pain and convinced of his imminent recovery, died and is buried at sea. We follow his body floating down, inspected by a shoal of fish who then stand aside to allow Gusev his final moment with an almost disinterested shark. It is fantastically beautiful writing – the whole story – and I recommend Rosamund Bartlett’s translation.

It’s 6.11am in the High Dependency unit.

Sunrise Over Wavertree

Posted on: November 15, 2014

I could give you the big handover notes, talk you through my medical history and we could get puzzled or outraged as to how I got to November 4th so sick that a slightly later 999 call would have been too late.

I could go with self-accusation: Billy Grahaming up to my bad self-destructive ways; put my 20-year-old self on trial; blame it on the hot knives, the cold flats, the revolutionary delusions and of course the boogie.

I could get all Erin Brocovitch about it and resolve to find the guilty of the medical profession who didn’t foresee this all happening at any point over the last 45 years.

But my concern isn’t ‘How the hell did I get so sick?’ but ‘Who the hell isn’t this sick?’ Because, you know, there were local factors in the case of my body, but the sickness of keeping on slogging away in desperation, in increasing depression, trudging up and down the same bastard roads for an occasional glimpse of a honey pot – yes, exactly like Cormac Mccarthy’s Winnie The Pooh – that’s where to find the class action.

But I’ll narrow it down again because the sun just rose over Wavertree, my first sight of the sky since last Tuesday. I have rich memories of the morning skyline in Gdansk 15 years ago, waking up eye to eye with church spires, and of sky-tall building work over Dhaka, 9 years ago, watching the immense blood orange sun from my hotel window. These trips were two of the great working experiences of my life and those moments, realising that I was here, seeing this, because I made the choice of being a writer, are among the most fulfilling I’ve known. And this moment – I’ve been sat out in a chair by the window; the Ozymandian towers in construction for the new Liverpool Royal Hospital are striping the view of Archbishop Blanch school, Mount Vernon and the stretch from Edge Lane south to Runcorn; I have a coffee and a new Bolano – correlates quite precisely with those euphoric moments abroad. I am here because I’m a writer.

Here because I’m a writer: the life I’ve had to live to fight for the retention of that core truth; the logic I’ve neglected to follow because my sense of who I am and what I should be was bigger; the reward or revenge you get for making that call. Everything that put me in here. Everything it’s given me while I have been here. Everything my life was supposed to be about while my insides were fermenting like squalid moonshine, while I was maintaining the distance of one microsleep on the motorway away from being shovelled into one of the cement mixers outside instead of arriving via the ambulance bay into this world of brilliant humans and caring machines.

Tell me about your plans for the rest of the day.

I’ll Be C-ing U

Posted on: November 14, 2014

It shouldn’t produce separation anxiety. It’s not like it’s meant to have been a holiday or an exchange trip or something huggable like that but there’s a bed being prepared for me in High Dependency and after the induced coma, period of intubation before the first hernia op, the two seizures on successive nights and getting back to communication with the outside world the last couple of days, my shift nurse Evangeline has just brought me a jelly but I’m struggling to find anything else to keep her busy. Looks like I’ll be out of the ICU tonight and, in the absence of a way home, I’m not sure I want to leave this family.

The first lesson I absorbed was to let these incredible professionals get on with their jobs. Show trust and it’ll be given back. Smile and wave at everyone because each one is doing something that’s going to lower the wall you’re trying to climb. Like the housekeeping staff who noticed I’d been writing my conversation when intubated, so provided a little wipe-down board and marked pen. Like Jess who managed to get me to focus on my breathing during my seizure two nights ago when I was ready to declare myself unavailable for future struggle. Every wise eyebrow raised by young Max as he swings past in slow-mo.

And that’s without the relationship that builds over a shift with a dedicated, alert, compassionate nurse dealing the best scientific and human care. The ICU really belongs to these nurses and, for those times when I was conscious, I’ll not forget Lucy, making the weirdest feeling of my life feel normal and under control; lovely Big Dave, who felt like a trusted friend within about 10 seconds; Dave Beard who I know will wage war on my behalf and that, if I ever had another kid, I’ll have to name it Sambucha in his honour; exquisite Kieron, a mighty strength applied to a precise point; Chrissie, whose last shifts before her maternity leave had got me back to what I recognised as being alive, even though I slipped back before she clocked off; Efriz, whose dancer’s poise and gentle pride in his work were as inspirational to watch as Ian’s care to not miss a detail or Sara’s immediate capacity to spark good spirits; or Alfie, against whose rock-like strength I was never allowed to slump during the four nights he kept me going.

Evangeline has brought me some bangers and mash. I’m going to miss this place.

I grant you, this idea of blogging my recovery scores low on originality, and negligible on cultural significance. It’s also turning me from a model, compliant patient to a pain in the arse who can’t leave his phone alone. More weak Baubyism in the comparative hassles of winking at a speech therapist for each letter and of spigoting the thoughts I have through the single thumb and predictive text method I have to use.

Generally, Minor Writer Makes Slow Recovery isn’t going to have them rushing to the hospital gates, holding out cheese pasties and Peperamis like sacred hosts for when I’m fully back on the solids. It’s not as if I’m Chekhov, drinking the last glass of champagne, brought to the room by Raymond Carver’s sleepy bell-boy (from the story Errand; read Janet Malcolm’s charting of how Carver’s fiction crept into official Chekhov biographies in the brilliant Reading Chekhov) – well, because, it’s not as if I’m Chekhov.

But there’s a part of the problem of being a writer that makes a stretch in ICU or something similar…let’s not say appealing, let’s leave the idea hanging like a distended scrotum after hernia surgery. It’s something to do with being monitors for suffering.

One of the things I noticed about all the brilliant contributions to Beta – Life was how optimistic mine seemed in comparison with the dystopia on display in pretty much every other piece. Now, this work was human, compassionate and there wasn’t an absence of hope from writers like Lucy Caldwell, Zoe Lambert or Adam Marek. And my story’s relative neutropia came about when I asked Francesco Mondada about whether he was optimistic (optimism having been a major response in my reading of Sara Maitland’s Moss Witch). Francesco was very dubious about progress coming without more powerful strides taken by commerce and military. So for a gentle family story involving writing and robots to happen in 2070, something had to have gone right.

So there is a context for my lack of dystopic gloom but…it doesn’t make you one of the cool kids. So that’s going to sound like I’m now catching up on the horror in order to get in that way. Maybe this is just a case of: Minor Writer Finally Finds Time To Write.

And that’s all the cultural significance I need.

The Claymatian Inside

Posted on: November 14, 2014

The bed-wetting reference of the previous post – while an entirely truthful piece of eye-catching amateur Christy Brown-ing, a little league Baubyism – wasn’t the story of last night. That was the piss that made its way into a bottle, held by Laura of the swinging hips, who snaffled the catch with the curly-haired aplomb of Graham Roope, dipping to his right to see an edge on a Geoff Arnold off-cutter find its way home.

Just a word of warning: you won’t need expert medical knowledge to follow this series of posts. You may, however, wish to research domestic and international cricket of the 1970s and 1980s to gain full technical appreciation.

Anyway, with no further catches getting spilled, I can see this being one route out of here: on my back but pissing in the right direction.

I’m still working out all the other ways. Last night and the night before, I’d watched my shift nurses prepare the discharge notes for my transfer to High Dependency, then watched that pristine care melt as my agonised, short breaths, the knuckles pawing for the floor and seizure sweats petrified around me in the claymatian shape of the inside of the ambulance, my last memory of life before the ICU.

Before Steph switched me back on, I was aware I’d been sedated – for how long that had been and how long I was conscious of it, I have no idea – and I worked out from voices I’d started to hear that I’d already come through something, that I was now going to be held in this place before the next something but that I seemed very strong and I have a lovely girlfriend. Remarkably, the first indication ICU nurses were able to give me of the strength I could draw on to get through this, came before they’d even woken me up.

The claymatian inside of the ambulance, of my head, of a muddy River Styx with thousands of naked Morph soldiers commando crawling across it, had until last night been features of the lit-up fantasies whenever I closed my eyes. The morphine was clearly at the root of that. It’s less easy to explain how much it separated my perceptions from reality in my ideas about the medical process taking place here: the casting of the staff and even other patients; the methods used to lull patients into the correct responses; the music playing under and against and sometimes within your pain; the backslang reminiscent at times of Poloni… It doesn’t require anywhere near that amount of puzzling to work out how clever science and skilled, meticulous, loving care are what have saved me on four big occasions so far and been life-affirming the rest of the time.

I’m doing this because what’s happening to me amongst these new friends in ICU feels like it needs more than a thank-you card. And, yes, it’s the journeyman writer’s hopeful step into the territory of the misery memoirist and if one way out of this is via a spot of promo on Woman’s Hour during a focus on Men’s Health and how we never act like we worry about our health until it’s no longer there, I’ll take that.

But if you want to support this blog,please keep reading, reposting, reacting, retweeting. This is raw pamphleteering and if you agree with it, please support the work of the ICU team at the Royal. Not so closely you get to write my sequel, mind you.

Last night I closed my eyes and saw the shadows of the ICU doors, windows and the corridors out. Nine days here and I’ve just arrived.

The Agonies and Alleyways

Posted on: November 13, 2014

My next blog was meant to be a taster for the new Comma Press science-into-fiction anthology, Beta-Life: Stories From An A – Life Future, to which I contributed The Longhand Option, a family tale of robots and writing in the year 2070 that involved fantastic support from my ‘science partner’, Francesco Mondada, and my editor Ra Page. In my story, Rosa, a writer, describes a finished story as being the

one that didn’t get to kill me.

Early on November 5th, years, days, months, hours, weeks of ignored, tolerated, undetected, late diagnosed, late presented, lifestyle-churned hernia and asthma problems nearly did kill me. They still could.

It’s 11.15pm, Wednesday 12 November 2014, and I’m writing with a pen and paper my shift nurse in the Royal Liverpool Hospital Intensive Care Unit, Alfie, brought me after changing my bed when I pissed it while listening to Sonny Rollins. I have a tube up my nose and down my through my gullet that’s draining stomach bile from my chest and lungs. I’m hooked up to drains, monitors and nebulisers.

In truth, my life has never held such dignity.

I am writing this as a result. This is the story to bring me back to life.

If you are a friend or colleague or acquaintance of mine who has noticed this and it’s the first time you knew I was ill, please accept apologise for the poor planning. And please keep checking this blog for further news so my wonderful girlfriend is able to stay on top of all she’s been left alone to deal with.

If you would like to help, keep reading, reposting, looking out for each other. I’m posting this just before 5pm on Thursday 14th. Ian gave me a shave this morning and Sara just washed my hair. So I am OK and ready to tell more – about the Agonies and Alleyways and the dignity that I am being given to lead the way back to a better life than before.

If you write stories, you will be asked what your stories are about and, unless you’re one of the people who can answer that they are about a boy wizard, this makes for a tough conversation. You could lay down a clueless cross-stitch of parameters – regarding form, genre, theme, plot, setting, motifs – that equate to saying ’round and red like a cricket ball, juicy like a rare steak and as good in soups as a mushroom’ in order to communicate the taste of a tomato. Assuming your inquisitor has had the patience to wait for your paroxysm of bitterness and self-loathing to subside and is still listening, you might get to explain that the remorseless necessity of living is what the fiction is about, and all the rest of it is just costume, props and lighting.

If you write stories, you will be asked what your stories are about and, unless you’re one of the people who can answer that they are about a boy wizard, this makes for a tough conversation. You could lay down a clueless cross-stitch of parameters – regarding form, genre, theme, plot, setting, motifs – that equate to saying ’round and red like a cricket ball, juicy like a rare steak and as good in soups as a mushroom’ in order to communicate the taste of a tomato. Assuming your inquisitor has had the patience to wait for your paroxysm of bitterness and self-loathing to subside and is still listening, you might get to explain that the remorseless necessity of living is what the fiction is about, and all the rest of it is just costume, props and lighting.

This points to what makes the café such fertile ground for the short story. In my first post about cafés on this blog, I said that “I suspect there are answers to be found here as to why short stories never really progress as a form – and why, conversely, they are always relevant.” The lack of progression in short fiction may be better expressed as an aesthetic conservatism: reliant on long-established virtues; in constant conversation with its own past. The relevance, on the other hand, is configured in its enduring functionality, the way the genre has always shaped itself to form part of an essential ‘kit’ for modern living, whenever and whatever ‘modern’ was at the time. A desultory glance through its contemporary history shows periods in which the short story has functioned as modern myth and parable, amiable commercial distraction, a format for bringing the stories of ordinary people into the literary salon, training ground for the writers of the Next Great Novel, and, in this digital age, its current status as the perfect literary accompaniment for portable, hand-held, capsule living – exemplified in Comma’s promotion of the Gimbal app.

The Gimbal enables you to access text and audio versions of short stories from (at last count) more than two dozen cities, simultaneously locating some of the stories’ settings and journeys in map and guidebook form. Like the mapping of Dublin in James Joyce’s proto-Gimbal, Ulysses, celebrated each June 16th on Bloomsday, and like Dante’s choice of Virgil the poet – rather than, say, Frommer’s – as his tour guide, there is an understanding here that you might discover the setting through the story, but that you might find a way to get lost regardless.

The reason short stories work in this context is because we can see ourselves so clearly in them that whatever seems alien or remote about the fictional landscape begins to make sense: we understand, at least, the characters’ relationship with it all. The reason a café setting works is because we understand what goes on there, without the gauze of a local or historical context. At about the mid-point of time between the first appearance of Ulysses and last Sunday’s Bloomsday festivities, Mary Lavin was one of the writers mapping Dublin and other parts of Ireland in her stories. But we can see, when we join her protagonist Mary, that this café, in Dublin in the early 1960s, could easily be in any other city at any other time:

The walls were distempered red above and the lower part was boarded, with the boards painted white. It was probably the boarded walls that gave it the peculiarly functional look you get in the snuggery of a public house or in the confessional of a small and poor parish church. For furniture there were only deal tables and chairs, with black-and-white checked tablecloths that were either unironed or badly ironed. But there was a decided feeling that money was not so much in short supply as dedicated to other purposes – as witness the paintings on the walls, and a notice over the fire-grate to say that there were others on view in a studio overhead, in rather the same way as pictures in an exhibition. They were for the most part experimental in their technique.

It’s not difficult to see that, though this is not the opening paragraph of the story, it’s likely to have been the beginning of the writing. In those first two sentences, we have the writer taking stock of where she has found herself and discovering, in the physicality of the café, a personality. This personality is crucial because it enables a lone character to be seen in interaction. When there are other characters around, it’s easy to set them up in counterpoint to one another (and this will happen as In A Café progresses) and define them accordingly, but Lavin shows how it can be done when your character is in solitude. The character’s gaze is what’s important here, and it can be read in the way the physical detail is presented. We are in Mary’s Point of View and, in addition to being told what she is seeing, we are invited to observed how she sees. The observation of the ‘either unironed or badly ironed’ tablecloths, for example, is revelatory, not as a critique of the tablecloths but for the trouble taken to distinguish between the two explanations for their creases. The thought process is apparent here: this is the sort of place where they aren’t preoccupied with appearance, simply that the tablecloths function to cover the tables, and this is because the people here have removed themselves from the way of life in which formalities of appearance are a priority; or this isn’t a question of a lack of care but of a lack of competence, and someone has tried to iron the tablecloths but these aren’t people equipped to fit their café out to the standard that would meet normal commercial expectations – the money, it is noted, goes elsewhere.

The automatic reading of this passage is of the author’s own first impression observations of The Clog, the Dublin café on which this is based, re-framed to suit the character and story she’s found. We can see close-up, though, that Lavin has fine-tuned the language to her character’s mind-set, enabling us to understand and know her so easily and well that each nuance within every phrase makes like the wind and cries Mary.

In this, her Mary is a worthy addition to the short story’s roster of great, sequestered heroines, such as Katherine Mansfield’s perpetually marginalised Miss Brill or the suddenly, temporarily single Louise Mallard in Kate Chopin’s The Story Of An Hour. She is a widow. Her husband, Richard, died when she was still a young woman, though evidently close enough to middle age for her new identity to accelerate that transition. I use the word ‘identity’, rather than status, because Richard’s death has been a fact of her life long enough for widow to have become absorbed within her sense of self. The very reason she is in the café relates to her widowhood. She is due to meet Martha, a younger woman widowed only the year before – the meeting ostensibly a recognition that they have sufficient common ground to bond. As she waits and we follow her gaze around the café, she considers that Richard and she, living in Meath on a large farm, would have been out of place there, having acquired the ‘faintly snobby’ bearing of landowners:

But it was a different matter to come here alone. There was nothing – oh, nothing – snobby about being a widow. Just by being one, she fitted into this kind of café.

Mary’s concise navigation through her thoughts about the tablecloth and, shortly after, her inspection of the ‘certainly stimulating’ abstract paintings on the walls tell us how the café is prompting her towards an understanding of what the identity of widowhood has done to her. The consideration of whether she fits into the café is linked to an overall preoccupation with what belonging even means anymore. Has ‘widow’ taken away the identity she had bound up with Richard but left nothing in its place? She decides what she thinks Johann van Stiegler’s artwork depicts but realises that this is definition and not opinion:

She knew what Richard would have said about them. But she and Richard were no longer one. So what would she say about them. She would say – what would she say?

In A Café, and Lavin’s writing as a whole, is full to the brim with moments like this, in which she articulates the uncomfortable nuances that sit between our better natures and the raw truth of our feelings. The conversation between Mary and the beautiful, young widow Maudie is immediately a kinetic surge of shared understanding which then acquires an awkward edge, utterly removed from any expectation of forlorn, noble suffering.  When a male customer, who turns out to be the café artist, Johann van Stiegler, joins in their conversation, the unease between Mary and Maudie escalates. The reason for going to the café disintegrates and the action, unusually for a story in our Café Shorts series, moves outside.

When a male customer, who turns out to be the café artist, Johann van Stiegler, joins in their conversation, the unease between Mary and Maudie escalates. The reason for going to the café disintegrates and the action, unusually for a story in our Café Shorts series, moves outside.

You get the feeling that Mary would prefer the company of Louise Mallard from Kate Chopin’s story. Like Chopin, Lavin was widowed at a relatively early age and what she took from this experience contributed to her most sharply observed stories. A Mary, who has lost a husband named Richard, though more recently, begins to come to terms with her solitude in In The Middle Of The Field, set on a large farm in Meath. It scarcely matters whether the Mary of this story is the protagonist of In A Café, nor whether the broad brushstrokes of synchronicity with Lavin’s life are matched in the finer detail: Lavin’s achievement is not that she drew her stories from her own truth, but that her stories touch upon fleeting, ambiguous truths within all our lives.

‘I’m lonely.’ That was all she could have said. ‘I’m lonely. Are you?’

The Hate Inside The Inkwell

Posted on: April 10, 2013

A couple of weeks ago, I joined in a discussion with fellow posters on The ‘Spill music blog on the issue of developing a fondness for music your partisan allegiances may once have instructed you to disdain. While citing my enduring contempt for Spandau Ballet’s True, I recognised that some affection has grown atop my identification of its vices, that I indeed now love the song for having been there for me to hate for so long. Even its specific offences – the overwrought, meaningless meaningfulness of lyrics like I bought a ticket to the world/ But now I’ve come back again – seem pardonable teenage misdemeanours with three decades of music listening as hindsight.

Precisely how I feel about an old pop song is neither here nor there, but it got me thinking about malignant creative influences. When asked to cite the influences that helped shape the writers, artists or even just the adults we have become, it’s natural to accentuate the positive. The writer I grew into certainly carried with him the early introductions to Shakespeare, Orwell and Harper Lee; the exposure via John Peel’s radio show to Linton Kwesi Johnson, John Cooper Clarke and Ivor Cutler, or via The Guardian and The Observer to James Cameron, John Arlott and Michael Frayn; the schoolboy aspirations to be Dickens, Fitzgerald, Conrad. But the transitions that occur throughout a life don’t happen as a victory parade; we also evolve by mutation, and among the many factors that shape us are our corrosive emnities.

I find little use for Hate these days, not proper hate, gut-knotting, blood-curdling; the thought-through hate; the uncut hate. There’s a quote from Joseph Conrad which reminds me of why he was one of my teenage literary heroes:

A writer without interest or sympathy for the foibles of his fellow man is not conceivable as a writer.

It’s a line I push to creative writing students now, the majority of whom were not alive in November 1990.

“And death…where is it?”

He sought his former accustomed fear of death and did not find it. “Where is it? What death?” There was no fear because there was no death.

In place of death there was light.

“So that’s what it is!” he suddenly exclaimed aloud. “What joy!”

Leo Tolstoy’s novella The Death Of Ivan Ilych encapsulates Conrad’s point. Ilych is not a likeable nor especially admirable man, and he is in possession of a considerable range of foibles. Tolstoy shies away from none of this in presenting Ilych’s life but, as the character slips towards death, our compassion is engaged. Beyond identifying with his struggle to comprehend what is killing him, and the despair in being forced to accept its irreversibility, we embrace Ilych fully in his final moments. When all the competing pressures are removed – around how to live, what to strive for, what greatness to achieve and what a signficant person to become – Ilych is able to free himself from the fear of death [above] and share with each of us the beautiful insignificance of our lives. And that really is the place to get to, since it’s where we’re all going.

Nobody this week has tried to make the case that Margaret Thatcher’s life was insignificant.

In my 2008 short story, A Different Sky, I wrote a scene set in November 1990 featuring some dancing in the street that may foreshadow some of April 2013’s transgressive street parties:

Max saw Will on the other side of Leece Street, by the hole-in-the-wall ‘Dog Burger’ bar, so he placed a clenched fist high in the air as a salute. Will crossed the road carefully, then skipped the rest of the way, pumping both his fists.

‘Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, YEESS!’ he yelled at Max.

‘Oh my God!’ Max shouted back, ‘I can’t believe it – finally!’

‘Eleven years, man – e-lev-en years.’

They stood and laughed in each other’s face. ‘I really can’t believe it,’ Max said again. Will ran on the spot. Max took Nelson out of the pram and raised him up towards the sky, like a scene from the adverts for Gillette.

Some might say that the day Thatcher left her office as Prime Minister was the right day for dancing, although it wasn’t us forcing her out but her erstwhile seemingly sycophantic Cabinet colleagues, and the Conservative government we opposed didn’t end for another six-and-a-half years. So that moment, in May 1997, might have been the right time to celebrate. Except tempering the euphoria was the awareness that the newly-elected Labour Party had become a very different being since Thatcher re-framed the national debate. Tony Blair’s goverment just had to show up to appear more socially progressive than John Major’s “Victorian family values” and Thatcherite policies like “Clause 28”, Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which sought to prohibit teaching and educational materials promoting the acceptability of homosexual relationships and which must seem to young people today like the basis for a Horrible Histories song. However, Blair styled himself as Thatcher’s political heir and New Labour’s economic and foreign policies remained true to her ideologies, while the retention of power underscored comparable authoritarianism. The salutations this week when an octagenerian dementia-sufferer died from a stroke, that we’d at least seen off the Devil of our age, can’t have gone unaccompanied by the understanding that, if Maggie Thatcher was ever a crusader against the welfare state, a symbol of social division and an enemy of the poor, then there’s a mob of millionaires who are very much alive, determinedly in charge, and bringing in divisive policies that exceed even her grandest follies. The time for dancing would have been when we’d defeated her politically, but our moment of victory never really came, and my 1990 revellers in A Different Sky unwittingly acknowledge this:

When [Nelson] came to rest on Dad’s shoulders, he could now see the top of another man’s head and there was hardly any hair there at all, just two grey patches at the sides. The man was walking past Dad and Will but he stopped for a moment, and his stiff grey suit made their denims seem even more soft and crumpled.

‘Great day, isn’t it, lads?’ the man said.

Will adjusted his voice to register his upbringing rather than his residence. ‘Absolutely, sir. Ding-dong, the witch is dead – now if we can just find a way to get rid of Bush and get out of the Gulf, we’ll be sorted.’

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Interviewed on the BBC website about his 2004 novel of the 1984-5 miners’ strike, GB84, David Peace commented on the impact of Thatcher’s confrontation with Arthus Scargill’s National Union of Mineworkers, whom she claimed represented “the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight [than the Argentinian “enemy without”, defeated in the Falklands War] and more dangerous to liberty.”:

It wasn’t the strike that changed lives and communities, it was the government policy and the forces they brought to bear upon pits and communities in order to close pits that changed lives. I think it’s hard for people in 2004, especially younger people, to understand the levels of sacrifice that people underwent in mining communities during 1984/85; the loss of, on average, 9000 pounds per miner, 11,000 arrested, 7000 injured, two men dead – that men and their families did this in order to defend not only their own jobs and communities, but also those of other men in other pits and communities. Those pits and communities are gone, organised labour is gone, socialism is gone and with it the heritage and culture that held people and places together. That government and their policies changed everybody’s lives, not only the ones that had the courage to at least stand and fight.

GB84 is a brilliant piece of writing and an exceptional work of multi-layered storytelling. Reading it was also one of the most unpleasant experiences I’ve had with any work of literature, so effective was it in pitching me right back into the moment of the miners’ strike, the high point of defiance against Thatcherism and the decisive factor, as Peace says, in bringing to an end the influence of organised labour in British political life. Hate was thick in the air supply then. In a suburban South London sixth form, nowhere near the war zones of what were still considered mining communities, I experienced feelings of solidarity and venomous hostility towards classmates based on their relative views on the strike. It was a daily consideration for over a year, the country felt like an emotional furnace, and it was nasty. Reading Peace’s novel, it was a shock to be reminded of how much hate had governed everyday life, but in the midst of the Thatcher years, the strike was just the most full-throated expression of the hate that muttered through the 80s.

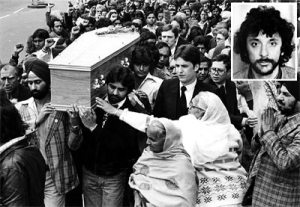

I don’t think it was Maggie Thatcher who taught me how to hate. For a non-white kid in a British city in the years after Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech, politicisation came early. The occasional insult in the street didn’t hurt much but it alerted me to racism, gave me – by way of the National Front – a focus for my nascent fear and loathing, and directed me (following my big brother’s tastes) to a mainly musical kindergarten for our political education. The Tom Robinson Band were stalwarts of the Rock Against Racism movement and were magisterially right-on, pushing anti-racism alongside feminism, unionism, opposition to police brutality and gay liberation. The anti-authoritarianism of Punk packaged hate in a discordant rage and cynicism that would have suited Thatcherism but related to the grey overture of the Wilson/Callaghan Labour years: entrenchment in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’, the strident pomp of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee and the Winter of Discontent, along with the rise of the NF. As formative to a clenched-fist political identity as The Clash were, though, nothing would give vague left-leaning beliefs such focus and purpose as Thatcher’s response to the death of Blair Peach.

In the weeks before the 1979 General Election, in which the National Front fielded over 300 candidates, the Party staged a campaign march through Southall, one of the areas of London most synonymous with immigrant settlement. Peach was a white New Zealander, working in London as a teacher, and part of the anti-racist counter-protest which clashed with riot police. Though it took 30 years for the Metropolitan Police to issue even this basic acceptance of claims made at the time, Peach was beaten to death with a blow to the head from a police officer. I was approaching 12 when this happened. I was not world weary. I had not seen it all. I was shocked and chilled that racism had got so bad that they were now killing white people to protect it. And then Mrs Thatcher, campaigning to be Prime Minister, offered her understanding of the situation:

“People rather fear being swamped by an alien culture.”

The man was dead and her compassion was for the racists who decided I didn’t belong in the only country I’d ever known. Ten days after Blair Peach’s head was caved in, Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister. She’d give me plenty of reasons to stoke that hatred over the years but it was there from Day One for me, and for millions of others who refuse to be hypocrites by joining in the steel toe-capped hagiography in progress, and the millions who promised themselves they’d live to see this day but didn’t make it. It’s political, but it’s always been personal.

I can testify that Thatcher was an immense influence on the reasons I had to write, on the things I chose to write about, on the decisions I made about what I wanted from my writing life and very likely the things I wouldn’t do in the interests of a writing career. But hating Maggie Thatcher isn’t a sustainable creative impulse. She did, though, make me take care to choose my words. So I won’t waste next Wednesday mourning her passing. If there’s a glass to be raised, I’ll raise it to Blair Peach.