Archive for the ‘Café Shorts’ Category

If you write stories, you will be asked what your stories are about and, unless you’re one of the people who can answer that they are about a boy wizard, this makes for a tough conversation. You could lay down a clueless cross-stitch of parameters – regarding form, genre, theme, plot, setting, motifs – that equate to saying ’round and red like a cricket ball, juicy like a rare steak and as good in soups as a mushroom’ in order to communicate the taste of a tomato. Assuming your inquisitor has had the patience to wait for your paroxysm of bitterness and self-loathing to subside and is still listening, you might get to explain that the remorseless necessity of living is what the fiction is about, and all the rest of it is just costume, props and lighting.

If you write stories, you will be asked what your stories are about and, unless you’re one of the people who can answer that they are about a boy wizard, this makes for a tough conversation. You could lay down a clueless cross-stitch of parameters – regarding form, genre, theme, plot, setting, motifs – that equate to saying ’round and red like a cricket ball, juicy like a rare steak and as good in soups as a mushroom’ in order to communicate the taste of a tomato. Assuming your inquisitor has had the patience to wait for your paroxysm of bitterness and self-loathing to subside and is still listening, you might get to explain that the remorseless necessity of living is what the fiction is about, and all the rest of it is just costume, props and lighting.

This points to what makes the café such fertile ground for the short story. In my first post about cafés on this blog, I said that “I suspect there are answers to be found here as to why short stories never really progress as a form – and why, conversely, they are always relevant.” The lack of progression in short fiction may be better expressed as an aesthetic conservatism: reliant on long-established virtues; in constant conversation with its own past. The relevance, on the other hand, is configured in its enduring functionality, the way the genre has always shaped itself to form part of an essential ‘kit’ for modern living, whenever and whatever ‘modern’ was at the time. A desultory glance through its contemporary history shows periods in which the short story has functioned as modern myth and parable, amiable commercial distraction, a format for bringing the stories of ordinary people into the literary salon, training ground for the writers of the Next Great Novel, and, in this digital age, its current status as the perfect literary accompaniment for portable, hand-held, capsule living – exemplified in Comma’s promotion of the Gimbal app.

The Gimbal enables you to access text and audio versions of short stories from (at last count) more than two dozen cities, simultaneously locating some of the stories’ settings and journeys in map and guidebook form. Like the mapping of Dublin in James Joyce’s proto-Gimbal, Ulysses, celebrated each June 16th on Bloomsday, and like Dante’s choice of Virgil the poet – rather than, say, Frommer’s – as his tour guide, there is an understanding here that you might discover the setting through the story, but that you might find a way to get lost regardless.

The reason short stories work in this context is because we can see ourselves so clearly in them that whatever seems alien or remote about the fictional landscape begins to make sense: we understand, at least, the characters’ relationship with it all. The reason a café setting works is because we understand what goes on there, without the gauze of a local or historical context. At about the mid-point of time between the first appearance of Ulysses and last Sunday’s Bloomsday festivities, Mary Lavin was one of the writers mapping Dublin and other parts of Ireland in her stories. But we can see, when we join her protagonist Mary, that this café, in Dublin in the early 1960s, could easily be in any other city at any other time:

The walls were distempered red above and the lower part was boarded, with the boards painted white. It was probably the boarded walls that gave it the peculiarly functional look you get in the snuggery of a public house or in the confessional of a small and poor parish church. For furniture there were only deal tables and chairs, with black-and-white checked tablecloths that were either unironed or badly ironed. But there was a decided feeling that money was not so much in short supply as dedicated to other purposes – as witness the paintings on the walls, and a notice over the fire-grate to say that there were others on view in a studio overhead, in rather the same way as pictures in an exhibition. They were for the most part experimental in their technique.

It’s not difficult to see that, though this is not the opening paragraph of the story, it’s likely to have been the beginning of the writing. In those first two sentences, we have the writer taking stock of where she has found herself and discovering, in the physicality of the café, a personality. This personality is crucial because it enables a lone character to be seen in interaction. When there are other characters around, it’s easy to set them up in counterpoint to one another (and this will happen as In A Café progresses) and define them accordingly, but Lavin shows how it can be done when your character is in solitude. The character’s gaze is what’s important here, and it can be read in the way the physical detail is presented. We are in Mary’s Point of View and, in addition to being told what she is seeing, we are invited to observed how she sees. The observation of the ‘either unironed or badly ironed’ tablecloths, for example, is revelatory, not as a critique of the tablecloths but for the trouble taken to distinguish between the two explanations for their creases. The thought process is apparent here: this is the sort of place where they aren’t preoccupied with appearance, simply that the tablecloths function to cover the tables, and this is because the people here have removed themselves from the way of life in which formalities of appearance are a priority; or this isn’t a question of a lack of care but of a lack of competence, and someone has tried to iron the tablecloths but these aren’t people equipped to fit their café out to the standard that would meet normal commercial expectations – the money, it is noted, goes elsewhere.

The automatic reading of this passage is of the author’s own first impression observations of The Clog, the Dublin café on which this is based, re-framed to suit the character and story she’s found. We can see close-up, though, that Lavin has fine-tuned the language to her character’s mind-set, enabling us to understand and know her so easily and well that each nuance within every phrase makes like the wind and cries Mary.

In this, her Mary is a worthy addition to the short story’s roster of great, sequestered heroines, such as Katherine Mansfield’s perpetually marginalised Miss Brill or the suddenly, temporarily single Louise Mallard in Kate Chopin’s The Story Of An Hour. She is a widow. Her husband, Richard, died when she was still a young woman, though evidently close enough to middle age for her new identity to accelerate that transition. I use the word ‘identity’, rather than status, because Richard’s death has been a fact of her life long enough for widow to have become absorbed within her sense of self. The very reason she is in the café relates to her widowhood. She is due to meet Martha, a younger woman widowed only the year before – the meeting ostensibly a recognition that they have sufficient common ground to bond. As she waits and we follow her gaze around the café, she considers that Richard and she, living in Meath on a large farm, would have been out of place there, having acquired the ‘faintly snobby’ bearing of landowners:

But it was a different matter to come here alone. There was nothing – oh, nothing – snobby about being a widow. Just by being one, she fitted into this kind of café.

Mary’s concise navigation through her thoughts about the tablecloth and, shortly after, her inspection of the ‘certainly stimulating’ abstract paintings on the walls tell us how the café is prompting her towards an understanding of what the identity of widowhood has done to her. The consideration of whether she fits into the café is linked to an overall preoccupation with what belonging even means anymore. Has ‘widow’ taken away the identity she had bound up with Richard but left nothing in its place? She decides what she thinks Johann van Stiegler’s artwork depicts but realises that this is definition and not opinion:

She knew what Richard would have said about them. But she and Richard were no longer one. So what would she say about them. She would say – what would she say?

In A Café, and Lavin’s writing as a whole, is full to the brim with moments like this, in which she articulates the uncomfortable nuances that sit between our better natures and the raw truth of our feelings. The conversation between Mary and the beautiful, young widow Maudie is immediately a kinetic surge of shared understanding which then acquires an awkward edge, utterly removed from any expectation of forlorn, noble suffering.  When a male customer, who turns out to be the café artist, Johann van Stiegler, joins in their conversation, the unease between Mary and Maudie escalates. The reason for going to the café disintegrates and the action, unusually for a story in our Café Shorts series, moves outside.

When a male customer, who turns out to be the café artist, Johann van Stiegler, joins in their conversation, the unease between Mary and Maudie escalates. The reason for going to the café disintegrates and the action, unusually for a story in our Café Shorts series, moves outside.

You get the feeling that Mary would prefer the company of Louise Mallard from Kate Chopin’s story. Like Chopin, Lavin was widowed at a relatively early age and what she took from this experience contributed to her most sharply observed stories. A Mary, who has lost a husband named Richard, though more recently, begins to come to terms with her solitude in In The Middle Of The Field, set on a large farm in Meath. It scarcely matters whether the Mary of this story is the protagonist of In A Café, nor whether the broad brushstrokes of synchronicity with Lavin’s life are matched in the finer detail: Lavin’s achievement is not that she drew her stories from her own truth, but that her stories touch upon fleeting, ambiguous truths within all our lives.

‘I’m lonely.’ That was all she could have said. ‘I’m lonely. Are you?’

“Would you please please please please please please please stop

talking?”

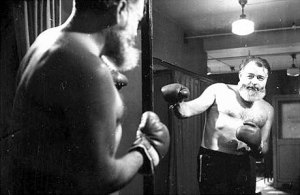

I’m going to take heed of what she asks here in the sense that I will attempt to talk about Ernest Hemingway’s 1927 story Hills Like White Elephants without including any spoilers about what the man and the woman are talking about.

I say this in full recognition that taking such precautions for anyone coming to a short story blog to read about a story analysed on probably every Creative Writing university degree course in the English-speaking world, brings to mind the time two women walked into a charity second-hand shop I was in last summer: “Ooh, look, Mum,” said one, pointing over to the music section, “Queen’s Greatest Hits!” I thought, how can that be exciting? There are people who care about music and some of them like Queen; then there are people who don’t care about music, and Queen have them covered too. If you like Queen, then surely to God you’ve had time and opportunity in your life to get hold of their Greatest Hits? Similarly, if you know anything about Hills Like White Elephants, reason would suggest that the undisclosed but “awfully simple”, “perfectly natural”, “perfectly simple” procedure under discussion, omerta may no longer be a requirement.

Nevertheless, I will steer around the matter simply because, having used it in creative writing teaching with undergraduates, I’ve seen that an isolated reading produces a range of interpretations as to the subtext of the central conversation. This, of course, means that two people will have the same words before them yet be reading two completely different stories. We might suppose that the strategy in storytelling is to have the reader understand what that story is. Of course, you may wish to leave certain matters open to conjecture and debate – what explains this behaviour? is the narrator as reliable as s/he would like us to believe? what happens next? – but you don’t expect the plot summary to be a multiple choice.

Nevertheless, I will steer around the matter simply because, having used it in creative writing teaching with undergraduates, I’ve seen that an isolated reading produces a range of interpretations as to the subtext of the central conversation. This, of course, means that two people will have the same words before them yet be reading two completely different stories. We might suppose that the strategy in storytelling is to have the reader understand what that story is. Of course, you may wish to leave certain matters open to conjecture and debate – what explains this behaviour? is the narrator as reliable as s/he would like us to believe? what happens next? – but you don’t expect the plot summary to be a multiple choice.

Actually, I don’t believe there is great room for dispute about Hemingway’s plot here: close attention to the emotional ebb and flow of the conversation shows it not to be a blur of Dadaist abstraction in the least, and further observation of the landscape either side of the railway bar, in which the two travelling Americans drink beer and Anis while waiting for their connecting train to Madrid, should dissolve any mystery. However, the very fact that the sparsity of more definitive signposts leads some readers to very different interpretations tells us a great deal about the remarkable quality of Hemingway’s writing here, working in the 3rd person objective voice he could very well have patented.

We are with these two people for just shy of three quarters of an hour and all we have of them is everything they say. Our reading is therefore a real time activity. We respond as we would if observing and eavesdropping random people in our normal lives. In this way, we can see how the café setting (as, despite the beer and the fire water, we’re entitled to think of it, this being mainland Europe) is fundamental to the authenticity of the couple’s conversational iceberg. Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard’s dabbed handkerchief in the Milford station café in Brief Encounter is a good indicator of the sort of protocol into which we’re entering in this environment: a place of non-belonging, in a pocket of restricted time, anonymous but under scrutiny of all those around who have nothing to do but wait and watch, the limits to which emotions can be expressed and truths can be articulated are all too apparent. In the case of the Madrid-bound Americans, there is the additional context that they are locked, together, within a de facto exile’s experience. The place they are in now is not a home, nor a home from home, nor even a destination. The type of relaxation available in the Central Perk model of Third Space establishments – a social space that can intersect with the work sphere; a public space in which to express a suitably modulated private identity – cannot be attempted here. Instead, we have enforced camaraderie and a mutual illiteracy when it comes to reading one another’s signals:

The place they are in now is not a home, nor a home from home, nor even a destination. The type of relaxation available in the Central Perk model of Third Space establishments – a social space that can intersect with the work sphere; a public space in which to express a suitably modulated private identity – cannot be attempted here. Instead, we have enforced camaraderie and a mutual illiteracy when it comes to reading one another’s signals:

The woman brought two glasses of beer and two felt pads. She put the

felt pads and the beer glasses on the table and looked at the man and the

girl. The girl was looking off at the line of hills. They were white in the sun

and the country was brown and dry.

“They look like white elephants,” she said.

“I’ve never seen one,” the man drank his beer.

“No, you wouldn’t have.”

“I might have,” the man said. “Just because you say I wouldn’t have

doesn’t prove anything.”

The talk replaces thoughts or one’s talk tramples on the other’s thoughts; in this, they occupy a similar space to Zoe Lambert’s squabbling interrailers in two of her stories in The War Tour. They drink together and the setting gives them a place to do this but those of us who can eavesdrop in both English and Spanish (and, by the magic of Hemingway’s decision to use English when Spanish is spoken, this means all of us) recognise that there are barriers and dependency issues there, as he has to do the talking for both of them:

The woman came out through the curtains with two glasses of beer and

put them down on the damp felt pads. “The train comes in five minutes,” she

said.

“What did she say?” asked the girl.

“That the train is coming in five minutes.”

The girl smiled brightly at the woman, to thank her.

Earlier, Hemingway jump-cuts through the sequence in which the man orders beer and then Anis del Toro and the woman brings the drinks over. He leaves in everything that’s said. Everything else that happens is silence, just as every conversation on every restaurant first date, or during every long-term couple’s rare bout of face time, is suspended when there is a member of the waiting staff hovering over the table. The couple’s conversation is not guarded because they are busy constructing a rabbit warren of metaphors and codes. They talk like this, in the situation they are in, because so would you. And when she strafes him with pleases to get him to stop talking, a nugget of dialogue that, out of context, seems stylised to the point of absurdity, can actually be appreciated as the one moment of unstoppable emotional honesty in the entire scene.

The conversation will pick up again, though, on the train, and then along the Gran Via or wherever they are headed. There is no obvious epiphany for the couple in Hills Like White Elephants. As we polish off the anis we’ve been sure we’ve been drinking, and set to hauling the luggage we just know has been sitting at our feet, the epiphany – that we’ve been drawn entirely into the scene as fellow customers – belongs to us.

The conversation will pick up again, though, on the train, and then along the Gran Via or wherever they are headed. There is no obvious epiphany for the couple in Hills Like White Elephants. As we polish off the anis we’ve been sure we’ve been drinking, and set to hauling the luggage we just know has been sitting at our feet, the epiphany – that we’ve been drawn entirely into the scene as fellow customers – belongs to us.

Morecambe’s restored art deco hotel, The Midland, offers its white screen to capture your projections. You sit in the tea room, below the vast whorls of the spiral staircase, and amidst the livery, potted palms, friezes and curved walls, and the pianist is playing These Foolish Things, you smell the “gardenia perfume lingering on a pillow”, dab the corner of your eye with a lace handkerchief or clench a pipe in your jaw and let the contents of the telegram held in your other hand wash over you…

Morecambe’s restored art deco hotel, The Midland, offers its white screen to capture your projections. You sit in the tea room, below the vast whorls of the spiral staircase, and amidst the livery, potted palms, friezes and curved walls, and the pianist is playing These Foolish Things, you smell the “gardenia perfume lingering on a pillow”, dab the corner of your eye with a lace handkerchief or clench a pipe in your jaw and let the contents of the telegram held in your other hand wash over you…

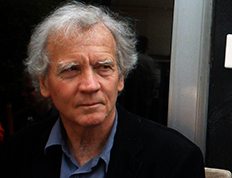

David Constantine, fresh from a reading the previous night at Lancaster’s Litfest, checked out of his hotel and, before hitting the motorway, took a detour to Lancaster’s coastal neighbour. He ordered a pot of tea and sat by the plate glass windows overlooking the epic wilds of Morecambe Bay, notorious since 2004 and the tragic deaths of eighteen Chinese migrant workers picking cockles in the “furrows and ridges” of the tide. The tea took an age to come and he might have given up in order to get back on the road to his home in Oxford but, from his little corner table, he was able to eavesdrop a couple whose romantic afternoon tea was being soured by their contrasting reactions to the relief in the entrance lounge, “Odysseus welcomed from the sea by Nausicaa” by the artist Eric Gill.

David Constantine, fresh from a reading the previous night at Lancaster’s Litfest, checked out of his hotel and, before hitting the motorway, took a detour to Lancaster’s coastal neighbour. He ordered a pot of tea and sat by the plate glass windows overlooking the epic wilds of Morecambe Bay, notorious since 2004 and the tragic deaths of eighteen Chinese migrant workers picking cockles in the “furrows and ridges” of the tide. The tea took an age to come and he might have given up in order to get back on the road to his home in Oxford but, from his little corner table, he was able to eavesdrop a couple whose romantic afternoon tea was being soured by their contrasting reactions to the relief in the entrance lounge, “Odysseus welcomed from the sea by Nausicaa” by the artist Eric Gill. Constantine was reminded of the tea room meeting between a man and a woman, no doubt in brand new art deco surroundings, observed by Katherine Mansfield and reproduced as A Dill Pickle, and he carried the incident away with him in his notebook. The result was Tea at the Midland, published by Comma Press, and it made him the predecessor to D.W. Wilson when he won the 2010 BBC National Short Story Award.

Constantine was reminded of the tea room meeting between a man and a woman, no doubt in brand new art deco surroundings, observed by Katherine Mansfield and reproduced as A Dill Pickle, and he carried the incident away with him in his notebook. The result was Tea at the Midland, published by Comma Press, and it made him the predecessor to D.W. Wilson when he won the 2010 BBC National Short Story Award.

Much of this is a lie, a fiction I’ve projected onto Constantine’s and indeed Mansfield’s processes – about either of which I know precisely nothing – based on elements of my own experience of taking tea at the Midland, where the order did indeed take an age to arrive and the water was indeed furrowed and ridged in the bay. There were no surfers, though, such as those watched by the woman in the story, behind the plate glass, projecting her ideals of grace and freedom onto their bobbing shapes:

In the din of waves and wind under that ripped-open sky they were enjoying themselves, they felt the life in them to be entirely theirs, to deploy how they liked best. To the woman watching they looked like grace itself, the

heart and soul of which is freedom. It pleased her particularly that they were attached by invisible strings to colourful curves of rapidly moving air.

How clean and clever that was!

Janet Malcolm, in her sublime study, Reading Chekhov – A Critical Journey [Granta, 2003], puts together a fascinating account of how the author’s death scene, in a German hotel room, has been re-created by a number of his biographers. To elements drawn from the eyewitness accounts, chiefly that of his widow Olga, of Chekhov’s final hours, other ‘facts’ have been added, most notably a sleepy young porter summoned in the middle of the night to bring champagne, a death-bed treat, to the room. The champagne was real, Malcolm tells us, but the porter was an invention by Raymond Carver in a story, Errand, written towards the end of his own life and published in 1988, which spun a fictional web around the events leading to Chekhov’s death. The manner in which the porter has come to be projected onto the ‘real’ story (albeit one easily disproved by less lazy researchers) suggests that Carver’s story has been read less as a fiction than as a preferred truth.

The woman, watching the surfers and constructing a fictional version of what she would like to be true about their moods and motivations, has been dealing in a preferred truth about the man with whom she is having tea, while his wife is at home, but projected, presumably in the act of cooking his dinner, onto the Midland’s curved white walls. She prefers, too, the truth she finds in the beauty of Gill’s frieze, in the gracious, graceful act of welcome he depicts, to the truth about Gill, whose diary accounts of his incest, paedophilia and bestiality were detailed in his biography, half a century after his death. The man can’t see other than with the hindsight these crimes have provided. He prefers his truth to come with moral certainties. When this isn’t the case – as when the woman asks whether “I should even have to learn to hate the sea because just out there, where that beautiful golden light is, those poor cockle-pickers drowned when the tide came in on them faster than they could run” – he wants no truck with it.

The woman, watching the surfers and constructing a fictional version of what she would like to be true about their moods and motivations, has been dealing in a preferred truth about the man with whom she is having tea, while his wife is at home, but projected, presumably in the act of cooking his dinner, onto the Midland’s curved white walls. She prefers, too, the truth she finds in the beauty of Gill’s frieze, in the gracious, graceful act of welcome he depicts, to the truth about Gill, whose diary accounts of his incest, paedophilia and bestiality were detailed in his biography, half a century after his death. The man can’t see other than with the hindsight these crimes have provided. He prefers his truth to come with moral certainties. When this isn’t the case – as when the woman asks whether “I should even have to learn to hate the sea because just out there, where that beautiful golden light is, those poor cockle-pickers drowned when the tide came in on them faster than they could run” – he wants no truck with it.

Constantine’s portrait of the man’s furious, controlling bluster, ostensibly intended for Gill but very much trained on his lover, skewers the hypocrisy of the hawkers of moral outrage. The undercurrent of menace is allowed to drift into the reader’s line of vision, never waved in front of our faces. We listen more closely to the woman, as she tries to contextualise her feelings about the Gill frieze by talking about the questionable moral character of Odysseus:

Odysseus was a horrible man. He didn’t deserve the courtesy he received from Nausikaa and her mother and father. I don’t forget that when I see

him coming out of hiding with the olive branch. I know what he has done already in the twenty years away. And I know the foul things he will do when he gets home. But at that moment, the one that Gill chose for his frieze, he is naked and helpless and the young woman is courteous to him and she knows for certain that her mother and father will welcome him at their hearth. Aren’t we allowed to contemplate such moments? – I haven’t read it, he said.

Those four words he speaks could be a backhand crashing into the side of her face, so brutal and disdainful is his attempt to sweep aside her point of view. That he doesn’t is a recognition of how the café environment allows a writer to construct surface and submerged narratives. Confined by the fact that “they were sitting at a table over afternoon tea in a place that had pretensions to style and decorum” only their wilting verbal communication is able to reflect the submerged frustration and rage. Outside, on the other side of the plate glass, the wind is ferocious, the waters wild, and there is beauty and uncomplicated joy in the surf. Inside, even the beauty comes with an overbearing moral shadow. The confined space generates the discord in the first place: the moral division over Gill’s artwork, represented in the couple’s views, is likely to be waged within any viewer who knows the back-story; anyone looking out from this swanky outpost cannot avoid projecting the fate of the cockle-pickers – their conditions of labour in the first place – onto the view of the tides. As with A Dill Pickle, the matter of the bill signals the end of the narrative. The restricted narrative space afforded by the Midland’s tea rooms allows the writer to project his fiction onto it, and re-align the truths held therein.

Meanwhile, if somebody opened up a door to my future

I’d probably turn away

And carry on reminiscing about the Armadillo Tea Rooms and Desperate Dan’s Café

There was, as mentioned in my 1997 poem Nobody’s Letting On, the Armadillo, where young men with Probe records bags and unkempt hair drank tea and ate quiche, and Desperate Dan’s – actually the café linked to the Open Eye photography gallery – which was run by a dedicated Evertonian socialist called Ronnie, who put the Blues’ miners strike-referencing 1984 FA Cup Final single, Here We Go, on the jukebox. And, at other times, there was the Tabac, where I heard the manager, Elaine, asking Adrian Henri if he was “still doing the writing?” More in line with the European bar bistro idea of café life, there was the iconic and recently departed Everyman Bistro , where my favourite character was a solo drinker – we called him Cheerful Charlie Chisholm – who wore a trilby and camel coat, suit and tie, and who would always scour each of the Bistro’s three rooms in expectation of finding the people he’d arranged to meet, and always find no-one.

, where my favourite character was a solo drinker – we called him Cheerful Charlie Chisholm – who wore a trilby and camel coat, suit and tie, and who would always scour each of the Bistro’s three rooms in expectation of finding the people he’d arranged to meet, and always find no-one.

But there was also Els Quatre Gats, Barcelona’s modernista hangout which incubated Picasso’s early career; and Le Forum in Arles, the precise topology of whose terrace has been imprinted on our consciousness by Van Gogh; there is the Savoy Patisserie, a bohemian enclave in Orhan Pamuk’s beloved Istanbul; and Café Momus, which provided Rodolfo, Mimi, Schaunard, Colline and Marcello thankfully cheap food and the odd cheap thrill in La Bohème.

But there was also Els Quatre Gats, Barcelona’s modernista hangout which incubated Picasso’s early career; and Le Forum in Arles, the precise topology of whose terrace has been imprinted on our consciousness by Van Gogh; there is the Savoy Patisserie, a bohemian enclave in Orhan Pamuk’s beloved Istanbul; and Café Momus, which provided Rodolfo, Mimi, Schaunard, Colline and Marcello thankfully cheap food and the odd cheap thrill in La Bohème. Writers sit and scrawl in such cafés, but they are also sustained by the life that goes on there, that spills in from and out to the cities – their cities – whose many lives sustain their writing.

Writers sit and scrawl in such cafés, but they are also sustained by the life that goes on there, that spills in from and out to the cities – their cities – whose many lives sustain their writing.

As soon as we land in the Greek café at the heart of Isaac Babel‘s The Aroma Of Odessa – he dispenses with the nicety of bringing us in through the doorway – we can recognise it as one of the cafés from our own memories and imaginations:

I am wandering between tables, making my way through the crowd, catching snippets of conversation. S., a female impersonator, walks past me. In his pale youthful face, in his tousled soft yellow hair, in his distant, shameless, weak-spirited smile is the stamp of his peculiar trade, the trade of being a woman. He has an ingratiating, leisurely, sinuous way of walking. His hips sway, but barely. Women, real women, love him. He sits silently among them, his face that of a pale youth and his hair soft and yellow. He smiles faintly at something, and the women smile faintly and secretively back – what they are smiling at only S. and the women know.

[translation by Peter Constantine in The Collected Stories of Isaac Babel, Norton 2002]

Nowadays, we call it the Third Space, the not-work, not-home in which we perfect a public manifestation of our private selves. Moving between the tables, we also move between tolerance, suspicion and understanding. This very short vignette is from the 1920s but the “aroma” of the title has been with him through his life, since his birth in the Odessa ghetto. It’s the smell of distance, of marginalia (indeed, of periphery) – the Jew from the ghetto in the port city at the edge of land, in an outpost of empire, amidst drag queens and their surreptitious shared smiles with the women, and

Fat, serene wives of movie-theater owners, thin cash-register girls (“true union members”), and fleshy, flabby, sagacious café-chantant agents, currently unemployed…

But it’s also an aroma of an intense blend and, in his passeggiata amongst the tables, Babel recognises the motifs of that uncut internationalism peculiar to port cities, fostered by the transit of produce and people. The recycling of themes and phrases mitigates towards meditation rather than narrative development, and brings to mind a poetic expression like Paul Célan’s Death Fugue, but there is a particular storytelling skill being deployed here, and it’s one any writer can attempt in his or her own familiar Third Space. What Babel seems to be taking is a snapshot but it’s also an X-ray. Another way of putting it is that the story is written from the point of view of the eternal outsider but it’s also written from beneath the skin of every inhabitant of the café, the city, his city, our cities.

Update: a reflection on Hemingway

Posted on: July 16, 2011

If you caught my appraisal of the Ernest Hemingway story, A Clean Well-Lighted Place in the Cafe Shorts series last month, you may be interested to know that the story is mentioned in the the latest instalment of Chris Power’s Guardian Books column, A brief survey of the short story.

If you caught my appraisal of the Ernest Hemingway story, A Clean Well-Lighted Place in the Cafe Shorts series last month, you may be interested to know that the story is mentioned in the the latest instalment of Chris Power’s Guardian Books column, A brief survey of the short story.

Power’s piece describes Ernest Hemingway’s blend of James Joyce’s “form as content” approach, “Hemingway’s [own] journalism training and the tenets of Pound’s Imagism, [resulting in] short, simple sentences mostly comprised of nouns and verbs. Adjectives and adverbs are used sparingly…” This is extremely useful in helping us to understand the evolution of the short story within modernism. What Hemingway did with his prose had, in Power’s words, “a measurable and profound” impact on short fiction (most tellingly, on Raymond Carver) that has followed ever since. The “cup of tea exercise” I brought you recently and my earlier strictures against writing “rowlingly” stem from attitudes entwined with Hemingway’s approach.

CLIVE: I'll tell you another thing gives me the horn. DEREK: What's that? CLIVE: The word "and". DEREK: Oh, "and". CLIVE: Whenever I see the word "and" in a book ..... DEREK: You-, you've picked a favourite of mine there. CLIVE: ..... I get so fucking horny, I- DEREK: Oh, fucking "and", mate. Ohh, Jesus, .....

We left our three generations of tika-taka park footballers on the verge of a story. By interrogating the scene, fantasising about its emotional backdrop and thereby injecting a narrative kinesis into the mundane moment, we can occasionally find quick routes to a story.

When Hubert Selby Jr saw a newspaper story about a man who locked his mother in a closet , he had not only an opening line –

, he had not only an opening line –

Harry locked his mother in the closet.

– but the whole novel of Requiem For The Dream. Asking and answering questions about this curious turn-of-events in a parent-child relationship allowed him to map out characters, back-stories and the parallel plots of the son’s heroin addiction and the mother’s Valium dependancy. What Selby did with the newspaper story, what we might do with our father and adult son going through their muffled rituals of playtime, is identify a central dynamic from which all else can be developed. We can actually strip away the rest. We can kick the football

into touch, close the park gates, send the kid off to boarding school, and build on whatever we’ve found in the father-son relationship that makes this a story worth telling. That story dynamic can be further deconstructed, though. Perhaps this isn’t about a father and son but about two different generations. Perhaps it’s not a personal tension between the two men but a case of each locked within the preoccupations that govern the life he is leading and the time of life he has reached.

So perhaps we can sit “in the corner of a tea-room, café, coffee shop; nursing cup after cup; observing the comings and goings…” and find our story dynamic in the contrasting attitudes of the two waiters on duty.

So perhaps we can sit “in the corner of a tea-room, café, coffee shop; nursing cup after cup; observing the comings and goings…” and find our story dynamic in the contrasting attitudes of the two waiters on duty.

Ernest Hemingway was a champion coffee shop sitter-and-writer so it’s only right we should turn to him for the second of our occasional Café Shorts series. In “A Clean, Well-Lighted Place”, the dimensions of the place in question are fundamental to the dynamic Hemingway is exploring. As the last customer, a suicidal, deaf drunkard throws back brandies and prevents the waiters from closing up for the night, we see in their conversation the tension between one who views the café as a place of work and the other, older waiter, who understands it as a place to be.

“Why didn’t you let him stay and drink?” the unhurried waiter asked. They were putting up the shutters. “It is not half-past two.”

“I want to go home to bed.”

“What is an hour?”

“More to me than to him.”

“An hour is the same.”

“You talk like an old man yourself. He can buy a bottle and drink at home.”

“It’s not the same.”

The story beautifully articulates the kind of philosophy that can only be perfected by sitting on your arse and keeping your throat lubricated. The younger waiter has everything but appreciates nothing: he has all the time in the world but he lets it go, hurries it past, allows it to fritter away while he waits for a better time to come. The older waiter has nothing, knows he has nothing and knows there is nothing – Hemingway gives him the bravura recital of the Lord’s Prayer with each noun replaced by “nada” – so he understands what the old man seeks in a clean, well-lighted place, where the task of being can be reduced to its most passive elements, where the act of living can be summed up, as the older waiter seems to do at the end, as “probably only insomnia. Many must have it.”

There is a profound anguish being portrayed here and yet the light remains. We continue to sit and watch, speculating on the lives of those in our field of vision, and waiting until the next story makes itself known to us.

We’ve taken a look at some of the factors that bring writers into coffee shops and that, once there, illuminate potential stories; and there was some discussion about the dramatic resonance these places can derive from personal memory and location. Let’s now grab a refill and take a closer look at how a short story narrative is galvanised by this type of setting.

The narrative of a story can be glimpsed in its opening and Katherine Mansfield‘s 1917 short story, A Dill Pickle, tells us all we’re going to need to know in this stunning first paragraph:

And then, after six years, she saw him again. He was seated at one of those little bamboo tables decorated with a Japanese vase of paper daffodils. There was a tall plate of fruit in front of him, and very carefully, in a way she recognized immediately as his “special” way, he was peeling an orange.

It’s an extraordinary first sentence, prompting a cascade of images suggesting what preceded the “And then…” The collapse of the previous six years into being the moment before seeing him “again” is devastating to us, before we have any idea who “she” and “him” are. As soon as physical details emerge, though, we start to realise we know them very well. It’s the tea room setting that does this. We can see him seated at the table, with its Oriental pretensions, doing just enough to trigger her memories of him – and we know what this is. The chance meetings we experience in tea rooms and coffee houses are never entirely by chance. Put another way, these aren’t the places you’d visit to avoid bumping into an old familiar face. We’ve gained more than a setting from the knowledge that this is a chance meeting across a plate of fruit. We get that these people have the time it will take them to get through their order –

He interrupted her. “Excuse me,” and tapped on the table for the waitress. “Please bring some coffee and cream.” To her: “You are sure you won’t eat anything? Some fruit, perhaps. The fruit here is very good.”

“No, thanks. Nothing.”

– either to re-open old wounds or to rekindle lost intimacy. What it was that took place in those six years; what they were to each other before then; the people they’ve been before this moment; what could happen next: all this will be determined in the time it takes to order, drink and pay for coffee and cream. Again, the mechanics of the venue underpin the choreography of the characters. What will this meeting inspire? Well, you can probably work it out if I tell you that she responds to an early compliment by raising her veil and unbuttoning her fur collar – entirely normal actions, or else she won’t feel the benefit when she goes out again – but that, left alone at the end with the bill, he points out to the waitress that “the cream has not been touched.”…”Please do not charge me for it.”

The mundane functions of all our lives can provide framing devices for narratives, and café culture offers these by the plateful. I’ve chosen a 94-year-old story that could have taken place today in your local Costa, but do you know, or have any favourite short stories set, entirely or mainly, in cafés? Let me know below…