Posts Tagged ‘film’

The Hate Inside The Inkwell

Posted on: April 10, 2013

A couple of weeks ago, I joined in a discussion with fellow posters on The ‘Spill music blog on the issue of developing a fondness for music your partisan allegiances may once have instructed you to disdain. While citing my enduring contempt for Spandau Ballet’s True, I recognised that some affection has grown atop my identification of its vices, that I indeed now love the song for having been there for me to hate for so long. Even its specific offences – the overwrought, meaningless meaningfulness of lyrics like I bought a ticket to the world/ But now I’ve come back again – seem pardonable teenage misdemeanours with three decades of music listening as hindsight.

Precisely how I feel about an old pop song is neither here nor there, but it got me thinking about malignant creative influences. When asked to cite the influences that helped shape the writers, artists or even just the adults we have become, it’s natural to accentuate the positive. The writer I grew into certainly carried with him the early introductions to Shakespeare, Orwell and Harper Lee; the exposure via John Peel’s radio show to Linton Kwesi Johnson, John Cooper Clarke and Ivor Cutler, or via The Guardian and The Observer to James Cameron, John Arlott and Michael Frayn; the schoolboy aspirations to be Dickens, Fitzgerald, Conrad. But the transitions that occur throughout a life don’t happen as a victory parade; we also evolve by mutation, and among the many factors that shape us are our corrosive emnities.

I find little use for Hate these days, not proper hate, gut-knotting, blood-curdling; the thought-through hate; the uncut hate. There’s a quote from Joseph Conrad which reminds me of why he was one of my teenage literary heroes:

A writer without interest or sympathy for the foibles of his fellow man is not conceivable as a writer.

It’s a line I push to creative writing students now, the majority of whom were not alive in November 1990.

“And death…where is it?”

He sought his former accustomed fear of death and did not find it. “Where is it? What death?” There was no fear because there was no death.

In place of death there was light.

“So that’s what it is!” he suddenly exclaimed aloud. “What joy!”

Leo Tolstoy’s novella The Death Of Ivan Ilych encapsulates Conrad’s point. Ilych is not a likeable nor especially admirable man, and he is in possession of a considerable range of foibles. Tolstoy shies away from none of this in presenting Ilych’s life but, as the character slips towards death, our compassion is engaged. Beyond identifying with his struggle to comprehend what is killing him, and the despair in being forced to accept its irreversibility, we embrace Ilych fully in his final moments. When all the competing pressures are removed – around how to live, what to strive for, what greatness to achieve and what a signficant person to become – Ilych is able to free himself from the fear of death [above] and share with each of us the beautiful insignificance of our lives. And that really is the place to get to, since it’s where we’re all going.

Nobody this week has tried to make the case that Margaret Thatcher’s life was insignificant.

In my 2008 short story, A Different Sky, I wrote a scene set in November 1990 featuring some dancing in the street that may foreshadow some of April 2013’s transgressive street parties:

Max saw Will on the other side of Leece Street, by the hole-in-the-wall ‘Dog Burger’ bar, so he placed a clenched fist high in the air as a salute. Will crossed the road carefully, then skipped the rest of the way, pumping both his fists.

‘Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, YEESS!’ he yelled at Max.

‘Oh my God!’ Max shouted back, ‘I can’t believe it – finally!’

‘Eleven years, man – e-lev-en years.’

They stood and laughed in each other’s face. ‘I really can’t believe it,’ Max said again. Will ran on the spot. Max took Nelson out of the pram and raised him up towards the sky, like a scene from the adverts for Gillette.

Some might say that the day Thatcher left her office as Prime Minister was the right day for dancing, although it wasn’t us forcing her out but her erstwhile seemingly sycophantic Cabinet colleagues, and the Conservative government we opposed didn’t end for another six-and-a-half years. So that moment, in May 1997, might have been the right time to celebrate. Except tempering the euphoria was the awareness that the newly-elected Labour Party had become a very different being since Thatcher re-framed the national debate. Tony Blair’s goverment just had to show up to appear more socially progressive than John Major’s “Victorian family values” and Thatcherite policies like “Clause 28”, Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which sought to prohibit teaching and educational materials promoting the acceptability of homosexual relationships and which must seem to young people today like the basis for a Horrible Histories song. However, Blair styled himself as Thatcher’s political heir and New Labour’s economic and foreign policies remained true to her ideologies, while the retention of power underscored comparable authoritarianism. The salutations this week when an octagenerian dementia-sufferer died from a stroke, that we’d at least seen off the Devil of our age, can’t have gone unaccompanied by the understanding that, if Maggie Thatcher was ever a crusader against the welfare state, a symbol of social division and an enemy of the poor, then there’s a mob of millionaires who are very much alive, determinedly in charge, and bringing in divisive policies that exceed even her grandest follies. The time for dancing would have been when we’d defeated her politically, but our moment of victory never really came, and my 1990 revellers in A Different Sky unwittingly acknowledge this:

When [Nelson] came to rest on Dad’s shoulders, he could now see the top of another man’s head and there was hardly any hair there at all, just two grey patches at the sides. The man was walking past Dad and Will but he stopped for a moment, and his stiff grey suit made their denims seem even more soft and crumpled.

‘Great day, isn’t it, lads?’ the man said.

Will adjusted his voice to register his upbringing rather than his residence. ‘Absolutely, sir. Ding-dong, the witch is dead – now if we can just find a way to get rid of Bush and get out of the Gulf, we’ll be sorted.’

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Interviewed on the BBC website about his 2004 novel of the 1984-5 miners’ strike, GB84, David Peace commented on the impact of Thatcher’s confrontation with Arthus Scargill’s National Union of Mineworkers, whom she claimed represented “the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight [than the Argentinian “enemy without”, defeated in the Falklands War] and more dangerous to liberty.”:

It wasn’t the strike that changed lives and communities, it was the government policy and the forces they brought to bear upon pits and communities in order to close pits that changed lives. I think it’s hard for people in 2004, especially younger people, to understand the levels of sacrifice that people underwent in mining communities during 1984/85; the loss of, on average, 9000 pounds per miner, 11,000 arrested, 7000 injured, two men dead – that men and their families did this in order to defend not only their own jobs and communities, but also those of other men in other pits and communities. Those pits and communities are gone, organised labour is gone, socialism is gone and with it the heritage and culture that held people and places together. That government and their policies changed everybody’s lives, not only the ones that had the courage to at least stand and fight.

GB84 is a brilliant piece of writing and an exceptional work of multi-layered storytelling. Reading it was also one of the most unpleasant experiences I’ve had with any work of literature, so effective was it in pitching me right back into the moment of the miners’ strike, the high point of defiance against Thatcherism and the decisive factor, as Peace says, in bringing to an end the influence of organised labour in British political life. Hate was thick in the air supply then. In a suburban South London sixth form, nowhere near the war zones of what were still considered mining communities, I experienced feelings of solidarity and venomous hostility towards classmates based on their relative views on the strike. It was a daily consideration for over a year, the country felt like an emotional furnace, and it was nasty. Reading Peace’s novel, it was a shock to be reminded of how much hate had governed everyday life, but in the midst of the Thatcher years, the strike was just the most full-throated expression of the hate that muttered through the 80s.

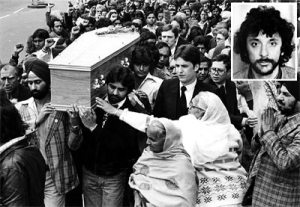

I don’t think it was Maggie Thatcher who taught me how to hate. For a non-white kid in a British city in the years after Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech, politicisation came early. The occasional insult in the street didn’t hurt much but it alerted me to racism, gave me – by way of the National Front – a focus for my nascent fear and loathing, and directed me (following my big brother’s tastes) to a mainly musical kindergarten for our political education. The Tom Robinson Band were stalwarts of the Rock Against Racism movement and were magisterially right-on, pushing anti-racism alongside feminism, unionism, opposition to police brutality and gay liberation. The anti-authoritarianism of Punk packaged hate in a discordant rage and cynicism that would have suited Thatcherism but related to the grey overture of the Wilson/Callaghan Labour years: entrenchment in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’, the strident pomp of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee and the Winter of Discontent, along with the rise of the NF. As formative to a clenched-fist political identity as The Clash were, though, nothing would give vague left-leaning beliefs such focus and purpose as Thatcher’s response to the death of Blair Peach.

In the weeks before the 1979 General Election, in which the National Front fielded over 300 candidates, the Party staged a campaign march through Southall, one of the areas of London most synonymous with immigrant settlement. Peach was a white New Zealander, working in London as a teacher, and part of the anti-racist counter-protest which clashed with riot police. Though it took 30 years for the Metropolitan Police to issue even this basic acceptance of claims made at the time, Peach was beaten to death with a blow to the head from a police officer. I was approaching 12 when this happened. I was not world weary. I had not seen it all. I was shocked and chilled that racism had got so bad that they were now killing white people to protect it. And then Mrs Thatcher, campaigning to be Prime Minister, offered her understanding of the situation:

“People rather fear being swamped by an alien culture.”

The man was dead and her compassion was for the racists who decided I didn’t belong in the only country I’d ever known. Ten days after Blair Peach’s head was caved in, Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister. She’d give me plenty of reasons to stoke that hatred over the years but it was there from Day One for me, and for millions of others who refuse to be hypocrites by joining in the steel toe-capped hagiography in progress, and the millions who promised themselves they’d live to see this day but didn’t make it. It’s political, but it’s always been personal.

I can testify that Thatcher was an immense influence on the reasons I had to write, on the things I chose to write about, on the decisions I made about what I wanted from my writing life and very likely the things I wouldn’t do in the interests of a writing career. But hating Maggie Thatcher isn’t a sustainable creative impulse. She did, though, make me take care to choose my words. So I won’t waste next Wednesday mourning her passing. If there’s a glass to be raised, I’ll raise it to Blair Peach.

You go weeks, a couple of months, without blogging about a short story so, when you do, you tell yourself it’s got to be a story that gets you right there, between the ribs. It’s got to be a story that walks the planet like an ambassador for everything you believe about writing. And you know the story you want to use. But it’s not your story, not really. It should be the story that first made you understand, made you believe. But the truth is you had no idea it existed until some guy put you onto it a year ago. You hope they won’t notice. But they’ll notice.

You go weeks, a couple of months, without blogging about a short story so, when you do, you tell yourself it’s got to be a story that gets you right there, between the ribs. It’s got to be a story that walks the planet like an ambassador for everything you believe about writing. And you know the story you want to use. But it’s not your story, not really. It should be the story that first made you understand, made you believe. But the truth is you had no idea it existed until some guy put you onto it a year ago. You hope they won’t notice. But they’ll notice.

So – full disclosure: if this post encourages you to track down Until Gwen, by the writer whose novels, Mystic River and Shutter Island, were made into acclaimed movies, credit must go to my colleague, John Sayle, at Liverpool John Moores University. John introduced the story to first year creative writers in a lecture ostensibly discussing dialogue technique. Certainly, Lehane has a fine ear for the dialogue within Americana’s underbelly, a comfortable fit within a tradition that links Damon Runyan with the likes of Elmore Leonard, Quentin Tarantino and George Pelacanos, joined lately and from a more northerly point by D.W. Wilson. Beyond that, though, the characters come across like you’re watching them in HD after finally jettisoning the old 16″ black & white – you witness them in pungent, raw flesh to the point where it becomes lurid – and Lehane’s dislocated 2nd person narrative propels you into a plot whose most brutal turns are disclosed to you like an opponent’s poker hand.

In quite other ways, and the area I wish to consider here, Until Gwen tells us a story about the writing process that should be instructive to would-be authors grappling with the distinction between having the ideas and making the writing. Dennis Lehane has said that he’d had the opening sentence of Until Gwen long before he had conceived of any of the characters, their relationships or what might happen to them. It’s no wonder, having come up with this line, Lehane knew that someday he’d have to build a story around it:

In quite other ways, and the area I wish to consider here, Until Gwen tells us a story about the writing process that should be instructive to would-be authors grappling with the distinction between having the ideas and making the writing. Dennis Lehane has said that he’d had the opening sentence of Until Gwen long before he had conceived of any of the characters, their relationships or what might happen to them. It’s no wonder, having come up with this line, Lehane knew that someday he’d have to build a story around it:

Your father picks you up from prison in a stolen Dodge Neon, with an 8-ball of coke in the glove compartment and a hooker named Mandy in the back seat.

The one guarantee is that, having read this, your reader is going to move on to the second sentence, which is also pretty good:

Two minutes into the ride, the prison still hanging tilted in the rearview, Mandy tells you that she only hooks part-time.

We must steer the Dodge Neon around any prospective spoilers but there is no jeopardy in noting that, below its carnival transgressive veneer, this opening contains the lead-weighted certainties of the thriller: when even the hooker is only part-time, nothing is quite what it first seems; we may be driving away from the prison, but it’s still there in our wonky eyeline; the orchestrator of the goody bag of petty crime presented to the central character on leaving prison is introduced to us as “Your father”; and even though we, the reader, have all of this shoved onto our lap, we have no idea who our proxy, “you”, is.

Through the remainder of the story, we discover the endgame from the four years’ thinking, forgetting and remembering time afforded to the young man, whom we later discover, as memory returns, was called “Bobby” by his lover, Gwen, conspicuous by her absence from the welcome party mentioned above. The thriller is played out between son and father, while Bobby’s memories of Gwen reveal a further great strength in Lehane’s prose, his facility for articulating male yearning. Gwen is typical of Lehane’s small town, big-hearted women who recognise something approaching nobility in nihilists like Bobby, who in turn represent hope, escape and salvation and whose relationships invariably collapse with the burden of this representation:

You find yourself standing in a Nebraska wheat field. You’re seventeen years old. You learned to drive five years earlier. You were in school once, for two months when you were eight, but you read well and you can multiply three-digit numbers in your head faster than a calculator, and you’ve seen the country with the old man. You’ve learned people aren’t that smart. You’ve learned how to pull lottery-ticket scams and asphalt-paving scams and get free meals with a slight upturn of your brown eyes. You’ve learned that if you hold ten dollars in front of a stranger, he’ll pay twenty to get his hands on it if you play him right. You’ve learned that every good lie is threaded with truth and every accepted truth leaks lies.

You’re seventeen years old in that wheat field. The night breeze smells of wood smoke and feels like dry fingers as it lifts your bangs off your forehead. You remember everything about that night because it is the night you met Gwen. You are two years away from prison, and you feel like someone has finally given you permission to live.

Until Gwen ends the way it does because it began the way it did. Lehane’s premise of bad men and botched heists delivers an operatic crescendo within the short story format. He has written through the ideas sparked by that opening line and, along the way, found this narrative. The methodology enables the characters and situations to take shape amidst a series of tropes with which Lehane is comfortable. The peculiar and deadly sprinkling of diamonds holding the small town in thrall equates to the child murders in Mystic River or the epidemic of stray dogs in Lehane’s long short story, Running Out Of Dog, which also features a woman as potential salvation-figure, as does another short story, Gone Down To Corpus. Meanwhile, Bobby’s quest for his own identity resonates with the story about identity suicide, ICU, for which Paul Auster’s City of Glass is also a touchstone.

All this expansion, from an anonymous beginning to the process whereby the story becomes embedded within the writer’s broader preoccupations, is significant. The story’s performative narrative plays itself out by resolving its central struggle but there is plenty left unresolved, deferring as it does to life’s natural messiness. I’ve seen readers speculate and debate about the morality of the main characters and the fates of those around them but a fascinating titbit about Until Gwen is that Dennis Lehane came away from the story every bit as curious about the characters as his readers were. The characters, he has written, “kept walking around in my head, telling me that we weren’t done yet, that there were more things to say about the entangled currents that made up their bloodlines and their fate.”

The result, the other prompt for which was a challenge to write a theatrical part for his actor brother, which would allow him to play (against type) a morally irredeemable character, was a short play, Coronado. To go into too many details about the additions and alterations made to the story would once more risk spoilers since the play ties up several of the story’s loose ends. It does so with elegance and in a way that suggests Lehane has created a new puzzle for himself with his first act, and resolved it in the second.

The result, the other prompt for which was a challenge to write a theatrical part for his actor brother, which would allow him to play (against type) a morally irredeemable character, was a short play, Coronado. To go into too many details about the additions and alterations made to the story would once more risk spoilers since the play ties up several of the story’s loose ends. It does so with elegance and in a way that suggests Lehane has created a new puzzle for himself with his first act, and resolved it in the second.

Coronado, the script providing the title for a collection otherwise comprising of Lehane’s short stories, stands alone impressively as a play, the strong-arm poetry of the 2nd person narrative in Gwen sculpted to a somewhat less naturalistic set of voices, emphasising perhaps the operatic strains I picked up from the story and very much at home in the American theatre of Arthur Miller or David Mamet. Yet it couldn’t have come about without the ellipses in the short story – had Lehane been fully aware of his characters’ fates, he might not have written the play, might have left them in the short story and that might, perhaps, have become a novel. This makes me wonder about the ethics of leaving matters unexplained. Do we owe our characters (never our readers, who can never be allowed to override our creative controls) answers? For all that they share storylines and sections of text, I am not sure it’s helpful to place Until Gwen and Coronado too close together in our imaginations, lest one text overpowers the other.

An alternative companion piece to Until Gwen might be Vincent Gallo’s brilliant 1998 auteur effort, Buffalo ’66. There are shades of Bobby’s parole disorientation in the opening scenes of Gallo’s petty criminal, newly released from prison with a full bladder and nowhere to relieve it, eventually kidnapping a young tap-dancer (Christina Ricci) in his frustration (although, if Gallo has a fictional role model here, it may be Patrick Dewaere’s superbly jittery shambles Franck, central to a disastrous heist and the most downbeat lovers-on-the-lam scenario imaginable in the 1979 French film Série noire). Whilst a different type of antagonist to the father in the Lehane story, Ben Gazzara’s Jimmy, the father of Gallo’s character, offers a complementary montage of charm and menace.

An alternative companion piece to Until Gwen might be Vincent Gallo’s brilliant 1998 auteur effort, Buffalo ’66. There are shades of Bobby’s parole disorientation in the opening scenes of Gallo’s petty criminal, newly released from prison with a full bladder and nowhere to relieve it, eventually kidnapping a young tap-dancer (Christina Ricci) in his frustration (although, if Gallo has a fictional role model here, it may be Patrick Dewaere’s superbly jittery shambles Franck, central to a disastrous heist and the most downbeat lovers-on-the-lam scenario imaginable in the 1979 French film Série noire). Whilst a different type of antagonist to the father in the Lehane story, Ben Gazzara’s Jimmy, the father of Gallo’s character, offers a complementary montage of charm and menace.

Julian Barnes, in a recent Guardian article, ahead of the reissue of Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End, for which he has written the introduction, discusses how Ford’s quartet of novels has come to be regarded as a tetralogy, with the final novel, Last Post, widely derided and commonly discarded. Indeed, save for a motif of a couple of logs of cedar wood thrown on the fire, Tom Stoppard’s acclaimed adaptation of Ford’s novels for BBC/HBO, which prompted the re-print, brings the parade to an end at the climax of book three. Barnes makes a persuasive case for Last Post but, in doing so, relates Graham Greene’s decision to dispose of the volume in an edition he edited in the 1960s. Greene accused the final book of clearing up the earlier volumes’ “valuable ambiguities.” I find Coronado a soulful re-imagining of Until Gwen, the more fascinating because the author has, in a way, re-interpreted his own work. But Greene’s phrase reminds us that ambiguity is a defining strength of the short story. Whether Lehane had done anything else with them or not, the success of his and many other short stories is that the characters might step out from the text, valuable ambiguities intact, and wander around the reader’s minds for years to come, insisting that we aren’t done yet.

Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) makes a valid point. Humour can be highly personal, unpredictable and idiosyncratic. It might, as Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) assures Tommy, come down to “just…you know, how you tell the story.”

Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) makes a valid point. Humour can be highly personal, unpredictable and idiosyncratic. It might, as Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) assures Tommy, come down to “just…you know, how you tell the story.”

On Tuesday 10th April, I’ll be conducting a pair of workshops as part of the 2012 Words Festival, Leigh and Wigan’s annual literary celebration. The theme is Humorous Short Fiction and this is to let you know, if you’re in the area, that there are places available to writers of all levels interested in the fraught business of writing short stories that make readers laugh.

There are any number of examples, from O Henry to a forthcoming Reel Time Short Stories feature, Woody Allen, of writers with comic timing and turn-of-phrase but with those – and many others who may not even have intended to string together gags – what provokes the laughter is the truth in the story. However absurd, the story takes itself seriously. However comedic the characters, they feel real. In Sea Oak by George Saunders, the narrator works as a waiter-cum-stripper in a kinky fighter pilot themed bar, ‘Joysticks’, where employees are not allowed to serve up full nudity so wear outsized ‘penile stimulators’ to wave at appreciative diners, who in turn score them according to cuteness. Here’s how Saunders nails the slappable management speak and the suppresses horror of the man deemed not cute enough to continue to earn a living this way. You shudder as you laugh:

There are any number of examples, from O Henry to a forthcoming Reel Time Short Stories feature, Woody Allen, of writers with comic timing and turn-of-phrase but with those – and many others who may not even have intended to string together gags – what provokes the laughter is the truth in the story. However absurd, the story takes itself seriously. However comedic the characters, they feel real. In Sea Oak by George Saunders, the narrator works as a waiter-cum-stripper in a kinky fighter pilot themed bar, ‘Joysticks’, where employees are not allowed to serve up full nudity so wear outsized ‘penile stimulators’ to wave at appreciative diners, who in turn score them according to cuteness. Here’s how Saunders nails the slappable management speak and the suppresses horror of the man deemed not cute enough to continue to earn a living this way. You shudder as you laugh:

After closing we sit on the floor for Debriefing. “There are times,” Mr. Frendt says, “when one must move gracefully to the next station in life, like for example certain women in Africa or Brazil, I forget which, who either color their faces or don some kind of distinctive headdress upon achieving menopause. Are you with me? One of our ranks must now leave us. No one is an island in terms of being thought cute forever, and so today we must say good-bye to our friend Lloyd. Lloyd, stand up so we can say good-bye to you. I’m sorry We are all so very sorry”

“Oh God,” says Lloyd. “Let this not be true.”

But it’s true. Lloyd’s finished. We give him a round of applause, and Frendt gives him a Farewell Pen and the contents of his locker in a trash bag and out he goes. Poor Lloyd. He’s got a wife and two kids and a sad little duplex on Self-Storage Parkway

“It’s been a pleasure!” he shouts desperately from the doorway, trying not to burn any bridges.

Let this not be true. But it’s true. Come for the laughs and stay for the truths at either of the workshops, whose details are below and can also be found on page 6 of the Words Festival brochure:

1] Humorous Short Fiction

Wigan Cricket Club, Bull Hey, off Parsons Walk

10am until 3.30pm

Cost £5

Booking essential. 01942 723 350

2] Ashton Writers with Dinesh Allirajah

Sam’s Bar, Warrington Rd, Ashton

7.30pm – 10pm

Cost: Free

Ashton Writers are hosting an open evening for those interested in humorous writing. Refreshments provided. Free but booking is essential – 01942 723 350.

And now we hood our enemies

to blind them. Keep an eye on that irony.[Michael Symmons Roberts, from ‘Hooded’, in The Half Healed (Cape Poetry, 2008)]

Within the Hermetic Spaces category, I’m developing the ideas around short fiction’s relationship with temporal and spatial confinement that have emerged from my Café Shorts musing and which I began to lay out in considering Anthony Doerr’s Memory Wall a few weeks ago. And, although I’m dealing with a short story in this post, Hermetic Spaces will also take in the mechanisms of writing and just being that this blog likes to discuss. The invitation to draw up a seat and join in the conversation should be taken for granted.

Hassan Blasim‘s The Reality And The Record might also have made a lateral contribution to the Reel Time Short Stories series. Blasim has released films in his native Iraq as well as in exile in Iraqi Kurdistan and since taking up residence in Finland. When I was writing that sentence, I thought twice and decided against describing Blasim as, first, a “respected” film-maker, and then a “successful” film-maker. Under dictatorship, to what does “respect” amount? In exile, what counts as “success”? The conditions Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright, writes about in his 2009 Comma Press collection The Madman Of Freedom Square, force us to interrogate platitudes and to re-consider all manner of language:

Hassan Blasim‘s The Reality And The Record might also have made a lateral contribution to the Reel Time Short Stories series. Blasim has released films in his native Iraq as well as in exile in Iraqi Kurdistan and since taking up residence in Finland. When I was writing that sentence, I thought twice and decided against describing Blasim as, first, a “respected” film-maker, and then a “successful” film-maker. Under dictatorship, to what does “respect” amount? In exile, what counts as “success”? The conditions Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright, writes about in his 2009 Comma Press collection The Madman Of Freedom Square, force us to interrogate platitudes and to re-consider all manner of language:

What I’m saying has nothing to do with my asylum request. What matters to you is the horror. If the Professor was here, he would say that the horror lies in the simplest of puzzles which shine in a cold star in the sky over this city. In the end they came into the cow pen after midnight one night. One of the masked men spread one corner of the pen with fine carpets. Then his companion hung a black banner inscribed: The Islamic Jihad Group, Iraq Branch. Then the cameraman came in with his camera, and it struck me that he was the same cameraman as the one with the first group. His hand gestures were the same as those of the first cameraman. The only difference was that he was now communicating with the others through gestures alone. They asked me to put on a white dishdasha and sit in front of the black banner. They gave me a piece of paper and told me to read out what was written on it: that I belonged to the Mehdi Army and I was a famous killer, I had cut off the heads of hundreds of Sunni men, and I had support from Iran. Before I’d finished reading, one of the cows gave a loud moo so the cameraman asked me to read it again. One of the men took the three cows away so that we could finish off the cow pen scene.

The narrator here was a Baghdad ambulance driver and is now an asylum seeker who has made his way to Sweden from the war in post-Saddam Iraq. In his testimony, he gives a graphic illustration of what might constitute a form of Hermetic Space that extends beyond a moment in time in one specific location. Certainly, the claimant has experienced confinement: he has been kidnapped, bundled into his stolen ambulance, driven over Baghdad’s Martyrs Bridge and held hostage. Prior to the video detailed in the quote above, he has already been recorded for a hostage video on behalf of his original kidnappers, before being dumped, kidnapped again by someone else and then put through the same process. He continues to be passed back and forth across Martyrs Bridge and around the terrorist organisations of Iraq: recording videos spouting a panoply of scripted confessions, each of which are filmed by the same man, whom he suspects to be the “Professor”, the eccentic director of the hospital Emergency Department for which he drove his ambulance.  The weary account of this horror story is told in tones of grim farce that bring to mind the character of Yossarian in Joseph Heller’s Catch 22. The ambulance driver’s perpetual entrapment, at the hands and in the viewfinder of these feverish, amateur content providers for Al-Jazeera’s rolling news, articulates a locked-in state and it’s only escape and the chance of asylum that offers a resolution.

The weary account of this horror story is told in tones of grim farce that bring to mind the character of Yossarian in Joseph Heller’s Catch 22. The ambulance driver’s perpetual entrapment, at the hands and in the viewfinder of these feverish, amateur content providers for Al-Jazeera’s rolling news, articulates a locked-in state and it’s only escape and the chance of asylum that offers a resolution.

However, it’s not simply the condition of kidnap victim that indicates a narrative unfolding within a Hermetic Space. The claim, that the war is being conducted as a Mexican stand-off on YouTube with most hits wins, cannot be taken as the truth, can it? Who is to know what the truth is of the man’s account? A fantasy wrought from the dislocating experience of kidnap? An elaborate cover-up for atrocities of his own? The story he thought he would need to secure asylum? Or even just a truth too unpalatable to be admissable? In zeroing in on the way war renders reality an impossibility to gauge, Blasim’s story is a good accompaniment to Tim O’Brien’s 1990 insertion of a Vietnam War tale into a narrative hall of mirrors, How To Tell A True War Story. It also points to the way in which War itself can be a narrative sealant, within which short stories can show us not so much the fixtures and fittings of a given conflict but a portrait of the human condition caught in a rapture of inhumanity.

Still from the final part of Masaki Kobayashi's Japanese WW2 trilogy, "Ningen No Joken III" ("The Human Condition")

We leave the last word to the Professor: ‘The world is just a bloody and hypothetical story. And we are all killers and heroes.’

S is for Shut Up and Deal

[also for Spoiler if you’ve never the seen the film, so beware…]

Writer/director Billy Wilder, co-writer I.A.L. Diamond, and star Jack Lemmon had combined two years earlier (with Joe E. Brown delivering the killer line) to create the immortal “Nobody’s perfect” dialogue at the end of Some Like It Hot. In 1960’s The Apartment, there’s something approaching perfection in the stuttering path Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine take, through endless work and love-based misdirections, to the romcom moment of epiphany depicted at the start of this closing sequence. But from the moment MacLaine enquires after the deck of cards, the brief remainder of the film becomes an outstanding example of letting the action speak for itself, that any writer would do well to heed. Yes, Lemmon attempts a gushing declaration of love but he’s cut short and handed the deck: “Shut up and deal.” Note MacLaine’s expert shuffle, a story in a few hand movements, and then, as the end credit appears, the way Lemmon follws that instruction, cards flying everywhere and bliss taking hold:

T is for Twist…Bust

Shirley’s just dumped Fred McMurray to see in the 1960s with you, she’s got the pixie haircut and she’s wearing that dress…those cards aren’t getting picked up anytime soon – it’s not as if you’re playing Felix in The Odd Couple for another eight years. Should Jack and Shirl eventually return to their game, they might get round to playing some blackjack, and they’ll know that, when you’re aiming for 21, if you twist too many times, you could end up bust. T could be for Tortuous Analogy because, as in card games, so it is in the short story: twist if you need to, but exercise caution. Writers approaching the short story via a Tales of the Unexpected, Guy de Maupassant or, indeed, Scooby Doo route, might believe that a twist in the tail is essential to a short story’s DNA.

Writers approaching the short story via a Tales of the Unexpected, Guy de Maupassant or, indeed, Scooby Doo route, might believe that a twist in the tail is essential to a short story’s DNA.

Maupassant’s influence, as one of the 19th century architects of what we now understand as the short story and the leading pioneer of the twist (and you thought it was Chubby Checker!), is powerful. Yes, he may wrong-foot the reader, but his characters aren’t constructs purely for the purpose of concealing the surprise at the ending: these are people living real lives. In The Necklace, the unfortunate, impoverished Mathilde, having borrowed a glittering diamond necklace to mask her poverty when attending a function related to her husband’s work, loses the necklace and she and her husband spend ten years raising the funds to buy a replacement to give back to the owner. The twist is that, when the owner has the dreadful secret explained to her, she tells Mathilde that the original necklace was a cheap fake. It’s a shock to the character, definitely, but the story isn’t about that shock: they’ve crippled themselves with debt and worked hard for ten years to pay for something they could have replaced for less than 500 francs – that’s a story about how crap life is when you’re skint. It’s not a twist at all: it’s a boorish, droning inevitability. Get the reader to understand your story, and the ending may momentarily startle but it won’t seem to have come from nowhere. Set out at every turn to fox and confuse your reader and it won’t just be the disgruntled old retainer in a phantom mask who’s plotting your downfall.

U is for “Uno, Dos…Uno, Dos, Tres, Cuatro…”

Gil Scott-Heron’s spoken count-in to The Bottle; Little Richard’s “A Wop-bop-a-loo-mop alop-bam-boom” into Tutti Frutti; George Harrison’s double-tracked guitar intro to I Wanna Hold Your Hand: if they were short stories and not songs, they’d read something like –

And then, after six years, she saw him again.

[Katherine Mansfield, A Dill Pickle]

Your father picks you up from prison in a stolen Dodge Neon, with an 8-ball of coke in the glove compartment and a hooker named Mandy in the back seat.

[Dennis Lehane, Until Gwen]

Miss Cicely Rodgers strapped her cock and balls into the Miracle Deluxe Vagina, which was made from skin-like flesh-coloured latex and came with fully adjustable straps to ensure a perfect fit and to hide any last sign of maleness.

[Alexei Sayle, Who Died And Left You In Charge?]

V is for Velázquez

It wasn’t just that he’d paint a dwarf as well as a Pope. It was that the depictions of the Dwarf Francisco Lezcano or the beggars and lowly workers, in the grounds around the royal or papal palaces, were proper portraits, investing the subjects with dignity unattainable in everyday society. It was also that Pope Innocent X could be portrayed in such a storytelling way, the terse, malevolent executive overflowing with human power but without too much divine grace in evidence. Stories can work like paintings in as many ways as there have been artistic movements, but the humanity in a Velázquez should be high on the list of aspirations.

It wasn’t just that he’d paint a dwarf as well as a Pope. It was that the depictions of the Dwarf Francisco Lezcano or the beggars and lowly workers, in the grounds around the royal or papal palaces, were proper portraits, investing the subjects with dignity unattainable in everyday society. It was also that Pope Innocent X could be portrayed in such a storytelling way, the terse, malevolent executive overflowing with human power but without too much divine grace in evidence. Stories can work like paintings in as many ways as there have been artistic movements, but the humanity in a Velázquez should be high on the list of aspirations.

W is for Watermelon

Thank you, the sex was lovely and, as you know, I’ve been very keen for it to happen for some time. And how delightful that the hotel puts watermelons in the room – so refreshing! I’m going to cut myself a slice. Would you like one?. I tell you what – this is lovely, but those black pips get on my nerves.

In Chekhov’s The Lady With The Dog, none of this is spoken by the male protagonist, Gurov, to his titular sexual conquest. He does cut himself a slice of the watermelon, which he eats slowly. And then Chekhov creates an image so excruciating, it’s enough to put you off the fruit for life: “At least half an hour passed in silence.” Girls, if he’s not at the very least asking you whether he’s got any pips stuck in his teeth within the first ten minutes, (a) get the message and get out of there, but not before (b) you shove the rest of the watermelon into him, not sliced up, and not necessarily via his mouth either.

X is for X-Ray Spex

Acknowledging the passing of Poly Styrene and celebrating the concise characterisation displayed in Warrior in Woolworth’s:

Y is for Yeast

That idea you’ve got, that you think would work in a story but you’ve not got a plot yet, or characters, or a setting or a way to begin or end it. It’s still there, still at work, and it’ll grow, so give it time.

That idea you’ve got, that you think would work in a story but you’ve not got a plot yet, or characters, or a setting or a way to begin or end it. It’s still there, still at work, and it’ll grow, so give it time.

Z is for Zelda Fitzgerald

The epitome of the writer’s muse. The ethics of drawing from your own life, and thereby the lives and personalities of those who share that life, are in a constant state of push-me-pull-me within each writer. You use your non-writing hand to wipe away the tears shed at the worst moments of your life because the other hand’s twitching for the nearest pen. Zelda was not simply a muse but an incisive writer herself. Scott knew this, of course, but does the selfishness required by a writer instinctively seek to overshadow this apparent equity in their relationship? Is there room for a second writer in your house? I’m only asking because I write short stories for a living, and I think my landlord might have got wind of this….

E is for Emotional Choreography

A line I’ll often throw out to students facing the construction of their first ever short story is to think of as simple a plot as possible, then make it simpler. If someone is telling you the summary of their short story plot, by the third or fourth “and then…” alarm bells are ringing out. Any short story, even the most fleeting vignette, requires a plot, whereby the characters do things, or things happen to them, or things are revealed to the reader, in a particular order – it’s just not always helpful to try to break it down in those terms. The idea of emotional choreography can be more useful when talking about a story in which little takes place in the way of external action or happening but we are witness to a shift in the internal state of the character(s), and the writer’s job is to arrange the steps by which they experience this shift. In Mansfield’s A Dill Pickle, the action can be summed up in terms of Vera unbuttoning and then rebuttoning her coat, with a conversation in between, but the emotional choreography is worthy of Gene Kelly.

A line I’ll often throw out to students facing the construction of their first ever short story is to think of as simple a plot as possible, then make it simpler. If someone is telling you the summary of their short story plot, by the third or fourth “and then…” alarm bells are ringing out. Any short story, even the most fleeting vignette, requires a plot, whereby the characters do things, or things happen to them, or things are revealed to the reader, in a particular order – it’s just not always helpful to try to break it down in those terms. The idea of emotional choreography can be more useful when talking about a story in which little takes place in the way of external action or happening but we are witness to a shift in the internal state of the character(s), and the writer’s job is to arrange the steps by which they experience this shift. In Mansfield’s A Dill Pickle, the action can be summed up in terms of Vera unbuttoning and then rebuttoning her coat, with a conversation in between, but the emotional choreography is worthy of Gene Kelly.

F is for Forbrydelsen

In 1995, Steven Bochco’s Murder One unravelled a single murder trial over 26 hour-long episodes. In a TV world in which the biorhythm of any crime was that it should be solved with time for a bit of banter at the end within the space of one hour, where the feature-length deliberations of Morse had seemed an impossible luxury, Murder One‘s progress towards the truth, led by Daniel Benzali’s Teddy Hoffman – the shaven-headed, ursine embodiment of Raymond Chandler’s line “Down these mean streets a man must go who is himself not mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid” – seemed more in keeping with the complexity and level of commitment we’d expect from a novel. When novelistic TV series, like The Sopranos, began to roll out of HBO and the other US networks, Bochco’s innovation receded into fond memory. Once high production values, narrative complexity and mumbled articulacy had become familiar to drama viewers, the crime-solving drama moved towards being the type of quality pulp that enabled you to switch your brain to autopilot without feeling you’d surrendered it to a tribe of reality show producers.

First airing in its native Denmark in 2007, but only reaching the UK when it was shown at the start of 2011 on BBC Four, Søren Sveistrup’s Forbrydelsen (The Killing, but the poncey insistence on the Danish also serves to differentiate it from the patchy US remake) took on the police procedural genre. While crime, in general, and police procedural or criminal psychologist narratives, are staples of the fiction bestseller lists, as well as the TV ratings, and while “fiction bestseller” equates to novels rather than short stories, it’s also possible to argue that the Whodunnit is a pertinent model for short fiction. Getting to the truth, or a good enough truth to enable us to move on, is as much a short story reader and a Chandleresque detective-figure can hope for over the course of a story. Forbrydelsen‘s first series ran for 20 episodes, but each episode represented one day of an investigation into the murder of a teenage girl, and one day at a time in the grieving process of her family. So, while it had a similar novelistic scope to Murder One – and in Sofie Gråbøl’s Sarah Lund, a shrewd, sensitive, tunnel-visioned Sam Spade for our times, and for the future series of the drama to come – it often carried itself like a short story. As one example, Lund’s relationship with chewing gum is a crucial aspect of Gråbøl’s performance but it’s one never given overt reference in the script: we just see her chewing her way through the barriers – bureaucratic, emotional, political – that hamper her progress towards the truth. The correlation between her chewing and the stress tells us enough so that when the frustration piles up to the extent that she bums a cigarette from her colleague, Jan Meyer, an arc, reaching back to way before we knew any of the characters, is completed.

First airing in its native Denmark in 2007, but only reaching the UK when it was shown at the start of 2011 on BBC Four, Søren Sveistrup’s Forbrydelsen (The Killing, but the poncey insistence on the Danish also serves to differentiate it from the patchy US remake) took on the police procedural genre. While crime, in general, and police procedural or criminal psychologist narratives, are staples of the fiction bestseller lists, as well as the TV ratings, and while “fiction bestseller” equates to novels rather than short stories, it’s also possible to argue that the Whodunnit is a pertinent model for short fiction. Getting to the truth, or a good enough truth to enable us to move on, is as much a short story reader and a Chandleresque detective-figure can hope for over the course of a story. Forbrydelsen‘s first series ran for 20 episodes, but each episode represented one day of an investigation into the murder of a teenage girl, and one day at a time in the grieving process of her family. So, while it had a similar novelistic scope to Murder One – and in Sofie Gråbøl’s Sarah Lund, a shrewd, sensitive, tunnel-visioned Sam Spade for our times, and for the future series of the drama to come – it often carried itself like a short story. As one example, Lund’s relationship with chewing gum is a crucial aspect of Gråbøl’s performance but it’s one never given overt reference in the script: we just see her chewing her way through the barriers – bureaucratic, emotional, political – that hamper her progress towards the truth. The correlation between her chewing and the stress tells us enough so that when the frustration piles up to the extent that she bums a cigarette from her colleague, Jan Meyer, an arc, reaching back to way before we knew any of the characters, is completed.

G is for Gil Scott-Heron

For all the reasons discussed here, and for the story told in a lyric like that for Pieces Of A Man:

Saw my Daddy meet the mailman

and I heard the mailman say,

“Now, don’t you take this letter too hard now, Jimmy,

‘cos they’ve laid off nine others today.”

But he didn’t know what he was saying.

He could hardly understand

that he was only talking to

pieces of a man.

H is for Hunger

“Cig?”

“Come on.”

“Bit of a break from smoking the Bible. Eh?”

“Oh aye.”

“Anyone work out which book is the best smoke?”

“We only smoke the Lamentations – right miserable cigarette.”

“Nice room.”

“Very clean…”

Hunger is Steve McQueen’s 2008 depiction of the 1981 IRA hunger strikes and dirty protests in the Maze prison, culminating in the death of the IRA prisoners’ Commanding Officer and newly-elected MP for Fermanagh and South Tyrone, Bobby Sands (Michael Fassbender). The film, drawing on McQueen’s background as a Turner Prize-winning video artist, deploys the essential short story technique of observed detail to extraordinary effect, so much so that the genuinely harrowing scenes of filth, brutality, a shocking assassination and Sands’ lingering demise acquire a perverse luxury through the beautifully patient storytelling. The heart of the film, for which co-writer Enda Walsh deserves credit, is a 17-minute dialogue between Fassbender’s Sands and Liam Cunningham’s Father Dominic Moran. With just one change of shot after ten minutes, we are able to focus on the dialogue’s humour, tension, tragedy and politics, not to mention the relief – for us and, we can empathise, for Sands – to have this break from literally wading in shit. This clip is just the first chunk. There are breezeblocks of exposition in fiction – and then there’s this expositional sculpture:

I is for iPadding

Nothing at all wrong with first person narrative. Nothing wrong with streams of consciousness nor with charismatic narrators who are the stars of their own stories. Writing what you know: tip-top advice. We often enter into the process of writing short stories as an act of self-expression or memoir; we come via the poetic statement that’s acquired a narrative; via the anecdote; via life’s epiphanies or forks-in-the-road. And when I say “we”, we write “I”. “I” in fiction can be a Nick Carraway or a Charles Ryder, the unremarkable foil to the Gatsbys and Flytes that absorb the light throughout those novels. But “I” can also be an obstruction to any given scene or story. A writer can wrap themselves around every detail so every piece of information about place, action or other characters comes to the reader already evaluated and filed under a particular conclusive emotion. It can make for a narrative effect similar to having someone sitting next to you, talking all the way through a film you’re trying to follow, not only drowning out the dialogue but explaining the plot as well. Simple(-sounding) solution: get “I” to step back and allow us to see the sunset, the actual sunset and not just what “I” thinks about the sunset – we know “I” can see it, otherwise we wouldn’t have it narrated to us, so we get very little from “I looked across to the West and saw in the sky a beautiful sunset.”

J is for Johnny Cash

When you can sing a song like this, you’ll get a great reaction from any audience, but when you’re stuck in Folsom Prison or, as the crowd is here, in San Quentin, then the visit of a country&western superstar, singing songs about the life you used to lead and the one you’ve got now, will be a story you’ll be telling each other every day until your release, and every day thereafter. Confinement is a key to short fiction. One night in a cell might get you enough material for a short novel, if you’re Roberto Bolaño (By Night In Chile), and a train journey might provide you with a murder mystery novel, but you’d beter hope that train’s the Orient Express: for the 13.34 from Irlam to Widnes, you’re going to need a short story. A restricted temporal or spatial setting alerts the reader to the idea that what happens here and now matters: what’s being described is not leading you to anything or anywhere else more important so stick with it, pay attention to every clue and, eventually, you’re going to find that sonofabitch that named you Sue.

K is for Stanley Kunitz

His last published poem, written and performed here at the age of 100. “What makes the engine go? Desire, desire, desire.” This is a poem that anyone, but especially each and every writer, needs to “remind me who I am” and this video is a short story in itself:

There’s no bettering Kurt Vonnegut when it comes to articulating the nebulous pursuit of a philosophy of writing. The objective of this series is to express nothing as grand as a writing philosophy nor as self-defeating as an attempt to pin down the ingredients of my, or anyone else’s, fiction. This is just a glossary that will gather together a series of creative touchstones in order to locate a system of shorthand for “the things I mean when I say the things I say that make you say ‘I guess you had to have been there’ when I say things about short story writing.” It’s not a reading list, because it’s clear that continued, wide and deep reading offers its own best system for understanding how writing works, but it rounds up some of the other stuff: the not-always-literary, bespoke moments that become the mantras.

In some of these, I’ll be reprising ideas I’ve floated in previous posts but shall include here so you can cut the pixels from your screen and reassemble them in a handy binder to file next to your Oxford English, your Roget and your dutiful copies of Will You Please Be Quiet, Please

-

A-D

A is for Albert Brooks in Broadcast News

It’s for everything he does as Aaron, the flop-sweating, unrequited, intellectual pinnacle and moral centre of Taxi creator James L. Brooks’ 1987 TV newsroom satire-cum-romcom which, if it didn’t directly influence Drop The Dead Donkey, recent BBC drama The Hour and Aaron Sorkin in general, must have slipped something into their water supply. But it’s mainly for this contender for both the Film Speech You Most Wished You’d Written and The Line You Most Want To Come Out With In Real Life, namely “Don’t get me wrong when I tell you that Tom, while being a very nice guy, is the devil.” An object lesson in how to make an enduringly salient point about capitalism and managerialism within an act of romantic emotional grandstanding, and it even finds a way to reference the subversion: “How d’you like that? I buried the lead.” If you’ve never been Aaron in this scene, you have no place at my table. If you’re Tom, see you in every workplace in the land next week; don’t forget the twee bloody biscuits you insist on bringing to the team meetings.

B is for the Bridge in A Night In Tunisia

Charlie Parker on A Night In Tunisia performs a precarious highwire act to get from the tune’s main theme into his opening solo. It’s one of the most famous “bridges” in jazz history. The composition of fiction can have a fractal quality as you visualise the story in discrete moments or plot points. Crossing the bridge from one of these moments to the next needn’t be as spectacular as Parker makes it but without a successful crossing, the coherence of your piece may never recover. There isn’t a single method for crossing your story’s bridges: sometimes it’ll be a compact, unfussy, functional action or description; sometimes you might want to elaborate. But knowing that you have these crossings to make can be the important first step.

C is for Cup of Tea

We’ve been here before: If I don’t care about the character when he or she is making a cup of tea, I’m not going to care when s/he’s saving the world.

D is for dice and women and jazz and booze

Beale Street by Langston Hughes

The dream is vague

And all confused

By dice and women

And jazz and booze.The dream is vague

Without a name

Yet warm and wavering

And soft as a flameThe loss

Of the dream

Leaves nothing

The same

And D here dovetails with another significant inspiration from Langston Hughes, his narrative for the Charles Mingus jazz piece, Scenes In The City, a pitch-perfect portrait of low-rent bohemia, chiseling out a recipe for survival from a life of struggle, shortage and disappointment: “And with the blues, whether I like it or not, I love the idea of living.”