Posts Tagged ‘evolution’

The Agonies and Alleyways

Posted on: November 13, 2014

My next blog was meant to be a taster for the new Comma Press science-into-fiction anthology, Beta-Life: Stories From An A – Life Future, to which I contributed The Longhand Option, a family tale of robots and writing in the year 2070 that involved fantastic support from my ‘science partner’, Francesco Mondada, and my editor Ra Page. In my story, Rosa, a writer, describes a finished story as being the

one that didn’t get to kill me.

Early on November 5th, years, days, months, hours, weeks of ignored, tolerated, undetected, late diagnosed, late presented, lifestyle-churned hernia and asthma problems nearly did kill me. They still could.

It’s 11.15pm, Wednesday 12 November 2014, and I’m writing with a pen and paper my shift nurse in the Royal Liverpool Hospital Intensive Care Unit, Alfie, brought me after changing my bed when I pissed it while listening to Sonny Rollins. I have a tube up my nose and down my through my gullet that’s draining stomach bile from my chest and lungs. I’m hooked up to drains, monitors and nebulisers.

In truth, my life has never held such dignity.

I am writing this as a result. This is the story to bring me back to life.

If you are a friend or colleague or acquaintance of mine who has noticed this and it’s the first time you knew I was ill, please accept apologise for the poor planning. And please keep checking this blog for further news so my wonderful girlfriend is able to stay on top of all she’s been left alone to deal with.

If you would like to help, keep reading, reposting, looking out for each other. I’m posting this just before 5pm on Thursday 14th. Ian gave me a shave this morning and Sara just washed my hair. So I am OK and ready to tell more – about the Agonies and Alleyways and the dignity that I am being given to lead the way back to a better life than before.

The Hate Inside The Inkwell

Posted on: April 10, 2013

A couple of weeks ago, I joined in a discussion with fellow posters on The ‘Spill music blog on the issue of developing a fondness for music your partisan allegiances may once have instructed you to disdain. While citing my enduring contempt for Spandau Ballet’s True, I recognised that some affection has grown atop my identification of its vices, that I indeed now love the song for having been there for me to hate for so long. Even its specific offences – the overwrought, meaningless meaningfulness of lyrics like I bought a ticket to the world/ But now I’ve come back again – seem pardonable teenage misdemeanours with three decades of music listening as hindsight.

Precisely how I feel about an old pop song is neither here nor there, but it got me thinking about malignant creative influences. When asked to cite the influences that helped shape the writers, artists or even just the adults we have become, it’s natural to accentuate the positive. The writer I grew into certainly carried with him the early introductions to Shakespeare, Orwell and Harper Lee; the exposure via John Peel’s radio show to Linton Kwesi Johnson, John Cooper Clarke and Ivor Cutler, or via The Guardian and The Observer to James Cameron, John Arlott and Michael Frayn; the schoolboy aspirations to be Dickens, Fitzgerald, Conrad. But the transitions that occur throughout a life don’t happen as a victory parade; we also evolve by mutation, and among the many factors that shape us are our corrosive emnities.

I find little use for Hate these days, not proper hate, gut-knotting, blood-curdling; the thought-through hate; the uncut hate. There’s a quote from Joseph Conrad which reminds me of why he was one of my teenage literary heroes:

A writer without interest or sympathy for the foibles of his fellow man is not conceivable as a writer.

It’s a line I push to creative writing students now, the majority of whom were not alive in November 1990.

“And death…where is it?”

He sought his former accustomed fear of death and did not find it. “Where is it? What death?” There was no fear because there was no death.

In place of death there was light.

“So that’s what it is!” he suddenly exclaimed aloud. “What joy!”

Leo Tolstoy’s novella The Death Of Ivan Ilych encapsulates Conrad’s point. Ilych is not a likeable nor especially admirable man, and he is in possession of a considerable range of foibles. Tolstoy shies away from none of this in presenting Ilych’s life but, as the character slips towards death, our compassion is engaged. Beyond identifying with his struggle to comprehend what is killing him, and the despair in being forced to accept its irreversibility, we embrace Ilych fully in his final moments. When all the competing pressures are removed – around how to live, what to strive for, what greatness to achieve and what a signficant person to become – Ilych is able to free himself from the fear of death [above] and share with each of us the beautiful insignificance of our lives. And that really is the place to get to, since it’s where we’re all going.

Nobody this week has tried to make the case that Margaret Thatcher’s life was insignificant.

In my 2008 short story, A Different Sky, I wrote a scene set in November 1990 featuring some dancing in the street that may foreshadow some of April 2013’s transgressive street parties:

Max saw Will on the other side of Leece Street, by the hole-in-the-wall ‘Dog Burger’ bar, so he placed a clenched fist high in the air as a salute. Will crossed the road carefully, then skipped the rest of the way, pumping both his fists.

‘Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, YEESS!’ he yelled at Max.

‘Oh my God!’ Max shouted back, ‘I can’t believe it – finally!’

‘Eleven years, man – e-lev-en years.’

They stood and laughed in each other’s face. ‘I really can’t believe it,’ Max said again. Will ran on the spot. Max took Nelson out of the pram and raised him up towards the sky, like a scene from the adverts for Gillette.

Some might say that the day Thatcher left her office as Prime Minister was the right day for dancing, although it wasn’t us forcing her out but her erstwhile seemingly sycophantic Cabinet colleagues, and the Conservative government we opposed didn’t end for another six-and-a-half years. So that moment, in May 1997, might have been the right time to celebrate. Except tempering the euphoria was the awareness that the newly-elected Labour Party had become a very different being since Thatcher re-framed the national debate. Tony Blair’s goverment just had to show up to appear more socially progressive than John Major’s “Victorian family values” and Thatcherite policies like “Clause 28”, Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which sought to prohibit teaching and educational materials promoting the acceptability of homosexual relationships and which must seem to young people today like the basis for a Horrible Histories song. However, Blair styled himself as Thatcher’s political heir and New Labour’s economic and foreign policies remained true to her ideologies, while the retention of power underscored comparable authoritarianism. The salutations this week when an octagenerian dementia-sufferer died from a stroke, that we’d at least seen off the Devil of our age, can’t have gone unaccompanied by the understanding that, if Maggie Thatcher was ever a crusader against the welfare state, a symbol of social division and an enemy of the poor, then there’s a mob of millionaires who are very much alive, determinedly in charge, and bringing in divisive policies that exceed even her grandest follies. The time for dancing would have been when we’d defeated her politically, but our moment of victory never really came, and my 1990 revellers in A Different Sky unwittingly acknowledge this:

When [Nelson] came to rest on Dad’s shoulders, he could now see the top of another man’s head and there was hardly any hair there at all, just two grey patches at the sides. The man was walking past Dad and Will but he stopped for a moment, and his stiff grey suit made their denims seem even more soft and crumpled.

‘Great day, isn’t it, lads?’ the man said.

Will adjusted his voice to register his upbringing rather than his residence. ‘Absolutely, sir. Ding-dong, the witch is dead – now if we can just find a way to get rid of Bush and get out of the Gulf, we’ll be sorted.’

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Interviewed on the BBC website about his 2004 novel of the 1984-5 miners’ strike, GB84, David Peace commented on the impact of Thatcher’s confrontation with Arthus Scargill’s National Union of Mineworkers, whom she claimed represented “the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight [than the Argentinian “enemy without”, defeated in the Falklands War] and more dangerous to liberty.”:

It wasn’t the strike that changed lives and communities, it was the government policy and the forces they brought to bear upon pits and communities in order to close pits that changed lives. I think it’s hard for people in 2004, especially younger people, to understand the levels of sacrifice that people underwent in mining communities during 1984/85; the loss of, on average, 9000 pounds per miner, 11,000 arrested, 7000 injured, two men dead – that men and their families did this in order to defend not only their own jobs and communities, but also those of other men in other pits and communities. Those pits and communities are gone, organised labour is gone, socialism is gone and with it the heritage and culture that held people and places together. That government and their policies changed everybody’s lives, not only the ones that had the courage to at least stand and fight.

GB84 is a brilliant piece of writing and an exceptional work of multi-layered storytelling. Reading it was also one of the most unpleasant experiences I’ve had with any work of literature, so effective was it in pitching me right back into the moment of the miners’ strike, the high point of defiance against Thatcherism and the decisive factor, as Peace says, in bringing to an end the influence of organised labour in British political life. Hate was thick in the air supply then. In a suburban South London sixth form, nowhere near the war zones of what were still considered mining communities, I experienced feelings of solidarity and venomous hostility towards classmates based on their relative views on the strike. It was a daily consideration for over a year, the country felt like an emotional furnace, and it was nasty. Reading Peace’s novel, it was a shock to be reminded of how much hate had governed everyday life, but in the midst of the Thatcher years, the strike was just the most full-throated expression of the hate that muttered through the 80s.

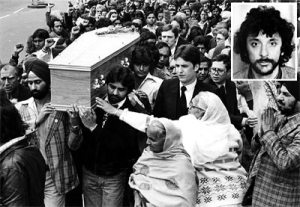

I don’t think it was Maggie Thatcher who taught me how to hate. For a non-white kid in a British city in the years after Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech, politicisation came early. The occasional insult in the street didn’t hurt much but it alerted me to racism, gave me – by way of the National Front – a focus for my nascent fear and loathing, and directed me (following my big brother’s tastes) to a mainly musical kindergarten for our political education. The Tom Robinson Band were stalwarts of the Rock Against Racism movement and were magisterially right-on, pushing anti-racism alongside feminism, unionism, opposition to police brutality and gay liberation. The anti-authoritarianism of Punk packaged hate in a discordant rage and cynicism that would have suited Thatcherism but related to the grey overture of the Wilson/Callaghan Labour years: entrenchment in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’, the strident pomp of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee and the Winter of Discontent, along with the rise of the NF. As formative to a clenched-fist political identity as The Clash were, though, nothing would give vague left-leaning beliefs such focus and purpose as Thatcher’s response to the death of Blair Peach.

In the weeks before the 1979 General Election, in which the National Front fielded over 300 candidates, the Party staged a campaign march through Southall, one of the areas of London most synonymous with immigrant settlement. Peach was a white New Zealander, working in London as a teacher, and part of the anti-racist counter-protest which clashed with riot police. Though it took 30 years for the Metropolitan Police to issue even this basic acceptance of claims made at the time, Peach was beaten to death with a blow to the head from a police officer. I was approaching 12 when this happened. I was not world weary. I had not seen it all. I was shocked and chilled that racism had got so bad that they were now killing white people to protect it. And then Mrs Thatcher, campaigning to be Prime Minister, offered her understanding of the situation:

“People rather fear being swamped by an alien culture.”

The man was dead and her compassion was for the racists who decided I didn’t belong in the only country I’d ever known. Ten days after Blair Peach’s head was caved in, Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister. She’d give me plenty of reasons to stoke that hatred over the years but it was there from Day One for me, and for millions of others who refuse to be hypocrites by joining in the steel toe-capped hagiography in progress, and the millions who promised themselves they’d live to see this day but didn’t make it. It’s political, but it’s always been personal.

I can testify that Thatcher was an immense influence on the reasons I had to write, on the things I chose to write about, on the decisions I made about what I wanted from my writing life and very likely the things I wouldn’t do in the interests of a writing career. But hating Maggie Thatcher isn’t a sustainable creative impulse. She did, though, make me take care to choose my words. So I won’t waste next Wednesday mourning her passing. If there’s a glass to be raised, I’ll raise it to Blair Peach.

Peripheral Vision

Posted on: August 19, 2011

Each of us, it would seem, orbits one another across ever-widening tracts of space. Is it that society, community, is what takes place in the furthest hinterland of our consciousness, or is it each one of us who is at the periphery of the larger narrative? Can writing, that adventure in solipsism, cope with the understanding that none of us was ever the story?

Even fiction, which has long since ceased to be based purely on the mythologies of Gods, Rulers and Heroes, can’t cope with absolute democracy. In any piece of fiction, characters will be central, secondary or peripheral. This even applies to stories told over several years, with dozens of characters engaged in hundreds of storylines: for a quarter of a century, on BBC TV’s Eastenders, whenever a major character has been called away to attend to a plot development, Tracey [played by Jane Slaughter, above] has covered for them on their stall or in their shift behind the bar of the Queen Vic.  In NBC’s The West Wing, in a belt-and-braces expression of periphery, Renée Estevez – a member of the Sheen acting dynasty who wasn’t sent to assassinate Marlon Brando, wasn’t in The Breakfast Club and isn’t the internet’s own Charlie Sheen – held down, as “Nancy”, a desk job in the Whitehouse during seven seasons of the drama about the Presidency of Jed Bartlet, played by her father. She greeted members of the staff and guests going in and out of the Oval Office and had not one moment of plot devoted to her life or work. This was in a series in which there were fully-fledged peripheral characters (economic advisers Ed and Larry; personal assistants Carol, Bonnie and Ginger) who also had no plots of their own but they at least got to engage in significant dialogue and do the occasional trademark walk’n’talk scene with the lead actors. Nancy said “Good morning, Mr President” and opened doors, and that was it. As viewers, we follow the lights that shine most brightly but, as writers, if we look to the shadows, to the lives of the Traceys and the Nancys, that’s where we can find our narratives.

In NBC’s The West Wing, in a belt-and-braces expression of periphery, Renée Estevez – a member of the Sheen acting dynasty who wasn’t sent to assassinate Marlon Brando, wasn’t in The Breakfast Club and isn’t the internet’s own Charlie Sheen – held down, as “Nancy”, a desk job in the Whitehouse during seven seasons of the drama about the Presidency of Jed Bartlet, played by her father. She greeted members of the staff and guests going in and out of the Oval Office and had not one moment of plot devoted to her life or work. This was in a series in which there were fully-fledged peripheral characters (economic advisers Ed and Larry; personal assistants Carol, Bonnie and Ginger) who also had no plots of their own but they at least got to engage in significant dialogue and do the occasional trademark walk’n’talk scene with the lead actors. Nancy said “Good morning, Mr President” and opened doors, and that was it. As viewers, we follow the lights that shine most brightly but, as writers, if we look to the shadows, to the lives of the Traceys and the Nancys, that’s where we can find our narratives.

Writing in The Guardian in May about Tracey Emin, Ali Smith – one of the key voices in contemporary short fiction – referenced a 1935 quote from Gertrude Stein in which she discussed how centuries of use in poetry had gradually sapped the “excitingness of pure being” from words which had once held tremendous resonance: “they were just rather stale literary words.” Narratives, too, grow stale and we need to pay attention to the ways in which storytellers will circumvent the glaring and the obvious. I’ve discussed the Simpsons Plot Detour previously, in reference to the way a typical Simpsons episode might embark on a narrative and then veer into a different story altogether after about five minutes. We can identify this as a device by the storytellers but it could also be a recognition of how the audience responds to narrative.

On our right, we have the 1947 painting, La Naissance de Vénus by the Belgian surrealist, Paul Delvaux. It’s a depiction of an event, a happening, and therefore it’s a story. And, in keeping with the narratives that our ancestors used to define and order our societies, it’s a story about a Deity. We can recognise Venus from the positioning of her hands and the tilt of her head but even a quick glance to our left at Botticelli’s canonical Birth of Venus

On our right, we have the 1947 painting, La Naissance de Vénus by the Belgian surrealist, Paul Delvaux. It’s a depiction of an event, a happening, and therefore it’s a story. And, in keeping with the narratives that our ancestors used to define and order our societies, it’s a story about a Deity. We can recognise Venus from the positioning of her hands and the tilt of her head but even a quick glance to our left at Botticelli’s canonical Birth of Venus shows us that Delvaux is drawing our gaze elsewhere. Delvaux’s goddess is not centrally located and is foregrounded to such a degree, she almost acts like a pillar blocking our view of part of the action at a sports ground. Almost immediately, we start to look past her – to the expression of exquisite sorrow on the face of what seems to be the maid to the right, to the naked bathers, the figures in the middle distance, the ghosts of giant faces suggested in the rock in the far distance, the ship which appears to lack a crew but must be piloted by someone…I’m guessing it’s Tracey from Eastenders.

shows us that Delvaux is drawing our gaze elsewhere. Delvaux’s goddess is not centrally located and is foregrounded to such a degree, she almost acts like a pillar blocking our view of part of the action at a sports ground. Almost immediately, we start to look past her – to the expression of exquisite sorrow on the face of what seems to be the maid to the right, to the naked bathers, the figures in the middle distance, the ghosts of giant faces suggested in the rock in the far distance, the ship which appears to lack a crew but must be piloted by someone…I’m guessing it’s Tracey from Eastenders.

In this late age for storytelling, the most effective route to a story may be to look to the edge of the crowd. The sense of what makes the world has changed to such a degree in the past century, we now have no doubts that, in society as in literature, the margins can reinvigorate the main page. Evolution tells us we’re all part of one sequence of molecular oscillation so no one story carries a ‘better’ truth than any other. Short stories must recognise this, because they rise and fall with the momentary, the illusory, the peripheral and the incidental.

Here’s an exercise for you: the recent story about the legendary French actor, Gérard Depardieu, urinating onto a CityJet plane’s carpet when refused permission to use the toilets prior to takeoff, was never going to be struggling for narrative potential. Like the appearance of the legendary footballer, Paul Gascoigne, at the fatal seige of a serial killer last summer, the nexus of spectacular human drama and a particular category of larger-than-life celebrity figure, immediately appeals to the sense that this was exactly what we used to expect of the ‘silly season’ and exactly what we used to expect from celebrities. The initial act, and the subsequent manner in which the story has played out in the media, may titillate or outrage us as consumers but needn’t concern us as writers. A fellow passenger’s eyewitness account of Depardieu’s actions on being caught short, in which she explained that “it all happened with courtesy,” is far more encouraging to our peripheral vision…

Here’s an exercise for you: the recent story about the legendary French actor, Gérard Depardieu, urinating onto a CityJet plane’s carpet when refused permission to use the toilets prior to takeoff, was never going to be struggling for narrative potential. Like the appearance of the legendary footballer, Paul Gascoigne, at the fatal seige of a serial killer last summer, the nexus of spectacular human drama and a particular category of larger-than-life celebrity figure, immediately appeals to the sense that this was exactly what we used to expect of the ‘silly season’ and exactly what we used to expect from celebrities. The initial act, and the subsequent manner in which the story has played out in the media, may titillate or outrage us as consumers but needn’t concern us as writers. A fellow passenger’s eyewitness account of Depardieu’s actions on being caught short, in which she explained that “it all happened with courtesy,” is far more encouraging to our peripheral vision…

Consider that mood of courtesy. Look past the embarrassed superstar, peeved cabin staff and bewildered passengers. Move down the aisle. Pause for a moment at the woman paying close attention to the scene, noting the levels of courtesy and preparing the statement she’ll make to reporters. Think about her spreading this observation back through the plane so that those, who were unable to see the kerfuffle or hear the splash into and out of an inadequately-sized Evian bottle, have acquired a sense of having been there, of having been privy to the courtesy, and part of the story. And then there’s one passenger for whom none of this has an impact. For this passenger, the famous man, his bladder, the plane’s carpet – that’s all the periphery. What is this passenger’s story?

The Physics Of Language

Posted on: May 23, 2011

The laces. The sole and the heel. The tongue. And the cuff, the counter, the quarter, the welt. The vamp and the eyelets. The aglet, the grommet, the last.

I’m talking cobblers, of course, but some may recognise that this list of the different parts of a shoe is a specific reference to a memorable passage from Don DeLillo’s 1997 novel, Underworld.  The passage, which can be read in full here, depicts a young man being instructed to pay attention to “the physics of language” – the names of things:

The passage, which can be read in full here, depicts a young man being instructed to pay attention to “the physics of language” – the names of things:

“Everyday things represent the most overlooked knowledge. These names are vital to your progress. Quotidian things. If they weren’t important, we wouldn’t use such a gorgeous Latinate word. Say it,” he said.

“Quotidian.”

“An extraordinary word that suggests the depth and reach of the commonplace.”

DeLillo is drawing an important line for us here, between notions of the abstract and the concrete.  On the one side, we have the idea and on the other we have the language. I’ve started on this in an earlier post but it’s one of those principles which, like the names of the parts of the shoe in the excerpt, doesn’t hurt to be drummed in via a little rote learning.

On the one side, we have the idea and on the other we have the language. I’ve started on this in an earlier post but it’s one of those principles which, like the names of the parts of the shoe in the excerpt, doesn’t hurt to be drummed in via a little rote learning.

An inexperienced writer will often confuse expressiveness and abstraction with inattention to detail. Joan Miró’s art gives us a handy reminder of where to draw the line. He resisted being labelled as an abstract artist:

For me a form is never something abstract: it is always a sign of something. It is a man, a bird, or something else. For me painting is never form for form’s sake

No matter that the art itself may work along abstract lines; no matter how it may express the artist/author’s subconscious and exercise that of the viewer/reader: what is employed in the creation of the work is the concrete detail of real life. This can be a tough line to walk. Am I suggesting the shutting down of the writer’s imagination? Am I arguing against pure, expressive lyricism, or positing a deadening Stakhanovite realism for the 21st century, like the offspring of a queasy union between Thomas Gradgrind and Dave Pelzer? I don’t think I’m debating the direction a writer’s work may take, or the generic and imaginative paths it may follow, but looking more at the building blocks of technique. It’s about understanding that concrete language is suffused with multitudes of meaning that are as readily apparent to a reader as they are to the writer. The abstract nature of emotion isn’t necessarily best expressed through the use of language that feels emotive, that appears to mimic the rage, passion, euphoria of the emotion itself.

This is something inexperienced writers can mistake. Five years ago, I was in Lagos and spent one morning delivering a workshop to a group of local writers. I asked them to represent their city, or Nigeria, in a single concrete image. I was offered a host of metaphors – the one I remember most clearly was that of a butterfly with blood-stained wings – from everyone in the group bar one of the writers, who  chose the yellow buses that attempt to provide a public transport service to the second most populous city in Africa. I knew about the yellow buses, having been there less than a week. Every artist in Lagos, looking to sell paintings to tourists, knows to paint the yellow buses. If you’ve only seen Lagos on the television, you’ll probably know about the yellow buses. And that’s why it worked: the poem this writer went on to produce described a scenario that felt real and, consequently, it made more emotional sense than a yellow busload of empty metaphors.

chose the yellow buses that attempt to provide a public transport service to the second most populous city in Africa. I knew about the yellow buses, having been there less than a week. Every artist in Lagos, looking to sell paintings to tourists, knows to paint the yellow buses. If you’ve only seen Lagos on the television, you’ll probably know about the yellow buses. And that’s why it worked: the poem this writer went on to produce described a scenario that felt real and, consequently, it made more emotional sense than a yellow busload of empty metaphors.

This is not a culturally-specific sermon and this is basic creative writing didacticism: “Only connect the prose and the passion and both will be exalted,” as E.M Forster blogged a century ago. Why is it such a commonplace for inexperienced writers to deal with just the laces and tongue of the prose before showing off their fancy footwork? I think there’s a clue in the phrase, “the physics of language.” It’s too easy for writers to absent themselves from the scientific workings of the world about which they are writing. It’s an abstraction borne out of a devotion to the spontaneity of the first draft. Going back over a text to check, for example, the name of “those black, metallic or plasticky bits on the ends of your shoelaces” may somehow seem a violation of your personal vision. Yet the rigour of inquiry, the determination not to let your language settle for vague stabs at aphorism but to attempt precision where possible, is not only a good habit but can add new dimensions to the work. Once you have the components of a thing, the way a thing works, the name of the thing – say, aglet – you begin to speculate as to how or whether your characters might have this knowledge and this, in turn, makes their hearts beat just a bit more persuasively than they had done before.

This is also why science provides a necessary enrichment of the writer’s process. The short fiction specialist publisher, Comma Press, is recognising this with science-themed anthologies. The Darwin 200 anniversaries in 2009 demonstrated how our understanding of what we are, where we are, what this is and where it’s heading has been, is being, revolutionised by the theories and discoveries of evolutionary biology, DNA and genome research, quantum physics. Scientists attempt to build narrative arcs into the first moment of the Big Bang; they seek to map the subatomic activity that takes place in what appears to be the empty space around our bodies; they discover common threads linking every life form on the planet, allowing us to understand ourselves as primates, molecules, stardust. Science is currently giving us the poetry, mapping the abstract worlds beyond our imagination. Writers have language – that’s our field – and we should rise to the challenge of seeking to understand how it works.

A reminder that some of the intersections between science and literature will be explored this THURSDAY 26 MAY in the Evolving Words showcase at Liverpool’s Poetry Cafe – details HERE

I’ll be appearing at the following event on Thursday 26th May at The Bluecoat in Liverpool. Here’s the blurb from the Evolving Words website:

Evolving Words at Bluecoat Chambers 26 May

Liverpool Poetry Cafe and the Bluecoat presentEvolving Words with Dinesh Allirajah, Valerie Laws, Ruthie Hartnoll, Craig Arnold, Greg Hurst, Siobhan Slater, Yahya Baggash, Jade Emily Bradford and Victoria Simms.

Hosted by Elizabeth Lynch.

Experiments, evil genes, the dating game, biodiversity, individual significance …

Established and emerging poets from Liverpool, Newcastle and Cambridge offer poetic responses to the radical ideas of Charles Darwin.

Thursday 26 May/7.30-9.30pm/the Bluecoat, School Lane, Liverpool L1 4BX

Tickets £3/£2 from Tickets & Information at the Bluecoat 0151 702 5324 and www.thebluecoat.org.uk

Evolving Words was a national project, supported by The Wellcome Trust that ran through 2009, to mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of Charles Darwin and the 150th anniversary of the publication of his Origins Of Species.  Poets, scientists and curators in Edinburgh, Newcastle, Liverpool, Manchester Birmingham and Cambridge worked with groups of young people to explore the life, theories and legacies of Darwin and respond with poetry, performance and film. I was the Liverpool poet, working in the Liverpool World Museum alongside Professor Greg Hurst and young poets including Ruthie, Craig, Siobhan and Yahya, who’ll all be reading on the 26th. We’ll be joined the Evolving Words co-ordinator Elizabeth Lynch, the Newcastle poet, Valerie Laws, and two of the young Cambridge poets. Jade and Victoria. This project was great to work on and it’s had a profound impact on my thinking and writing since. Scientific reasoning offers a welcoming cradle for ideas that can’t be readily worked out within the short story disciplines I observe with my main work, so gravitate towards the personal and the poetic. If you’re in the area, come along and study some specimens.

Poets, scientists and curators in Edinburgh, Newcastle, Liverpool, Manchester Birmingham and Cambridge worked with groups of young people to explore the life, theories and legacies of Darwin and respond with poetry, performance and film. I was the Liverpool poet, working in the Liverpool World Museum alongside Professor Greg Hurst and young poets including Ruthie, Craig, Siobhan and Yahya, who’ll all be reading on the 26th. We’ll be joined the Evolving Words co-ordinator Elizabeth Lynch, the Newcastle poet, Valerie Laws, and two of the young Cambridge poets. Jade and Victoria. This project was great to work on and it’s had a profound impact on my thinking and writing since. Scientific reasoning offers a welcoming cradle for ideas that can’t be readily worked out within the short story disciplines I observe with my main work, so gravitate towards the personal and the poetic. If you’re in the area, come along and study some specimens.