Posts Tagged ‘dickens’

The Hate Inside The Inkwell

Posted on: April 10, 2013

A couple of weeks ago, I joined in a discussion with fellow posters on The ‘Spill music blog on the issue of developing a fondness for music your partisan allegiances may once have instructed you to disdain. While citing my enduring contempt for Spandau Ballet’s True, I recognised that some affection has grown atop my identification of its vices, that I indeed now love the song for having been there for me to hate for so long. Even its specific offences – the overwrought, meaningless meaningfulness of lyrics like I bought a ticket to the world/ But now I’ve come back again – seem pardonable teenage misdemeanours with three decades of music listening as hindsight.

Precisely how I feel about an old pop song is neither here nor there, but it got me thinking about malignant creative influences. When asked to cite the influences that helped shape the writers, artists or even just the adults we have become, it’s natural to accentuate the positive. The writer I grew into certainly carried with him the early introductions to Shakespeare, Orwell and Harper Lee; the exposure via John Peel’s radio show to Linton Kwesi Johnson, John Cooper Clarke and Ivor Cutler, or via The Guardian and The Observer to James Cameron, John Arlott and Michael Frayn; the schoolboy aspirations to be Dickens, Fitzgerald, Conrad. But the transitions that occur throughout a life don’t happen as a victory parade; we also evolve by mutation, and among the many factors that shape us are our corrosive emnities.

I find little use for Hate these days, not proper hate, gut-knotting, blood-curdling; the thought-through hate; the uncut hate. There’s a quote from Joseph Conrad which reminds me of why he was one of my teenage literary heroes:

A writer without interest or sympathy for the foibles of his fellow man is not conceivable as a writer.

It’s a line I push to creative writing students now, the majority of whom were not alive in November 1990.

“And death…where is it?”

He sought his former accustomed fear of death and did not find it. “Where is it? What death?” There was no fear because there was no death.

In place of death there was light.

“So that’s what it is!” he suddenly exclaimed aloud. “What joy!”

Leo Tolstoy’s novella The Death Of Ivan Ilych encapsulates Conrad’s point. Ilych is not a likeable nor especially admirable man, and he is in possession of a considerable range of foibles. Tolstoy shies away from none of this in presenting Ilych’s life but, as the character slips towards death, our compassion is engaged. Beyond identifying with his struggle to comprehend what is killing him, and the despair in being forced to accept its irreversibility, we embrace Ilych fully in his final moments. When all the competing pressures are removed – around how to live, what to strive for, what greatness to achieve and what a signficant person to become – Ilych is able to free himself from the fear of death [above] and share with each of us the beautiful insignificance of our lives. And that really is the place to get to, since it’s where we’re all going.

Nobody this week has tried to make the case that Margaret Thatcher’s life was insignificant.

In my 2008 short story, A Different Sky, I wrote a scene set in November 1990 featuring some dancing in the street that may foreshadow some of April 2013’s transgressive street parties:

Max saw Will on the other side of Leece Street, by the hole-in-the-wall ‘Dog Burger’ bar, so he placed a clenched fist high in the air as a salute. Will crossed the road carefully, then skipped the rest of the way, pumping both his fists.

‘Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, YEESS!’ he yelled at Max.

‘Oh my God!’ Max shouted back, ‘I can’t believe it – finally!’

‘Eleven years, man – e-lev-en years.’

They stood and laughed in each other’s face. ‘I really can’t believe it,’ Max said again. Will ran on the spot. Max took Nelson out of the pram and raised him up towards the sky, like a scene from the adverts for Gillette.

Some might say that the day Thatcher left her office as Prime Minister was the right day for dancing, although it wasn’t us forcing her out but her erstwhile seemingly sycophantic Cabinet colleagues, and the Conservative government we opposed didn’t end for another six-and-a-half years. So that moment, in May 1997, might have been the right time to celebrate. Except tempering the euphoria was the awareness that the newly-elected Labour Party had become a very different being since Thatcher re-framed the national debate. Tony Blair’s goverment just had to show up to appear more socially progressive than John Major’s “Victorian family values” and Thatcherite policies like “Clause 28”, Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act, which sought to prohibit teaching and educational materials promoting the acceptability of homosexual relationships and which must seem to young people today like the basis for a Horrible Histories song. However, Blair styled himself as Thatcher’s political heir and New Labour’s economic and foreign policies remained true to her ideologies, while the retention of power underscored comparable authoritarianism. The salutations this week when an octagenerian dementia-sufferer died from a stroke, that we’d at least seen off the Devil of our age, can’t have gone unaccompanied by the understanding that, if Maggie Thatcher was ever a crusader against the welfare state, a symbol of social division and an enemy of the poor, then there’s a mob of millionaires who are very much alive, determinedly in charge, and bringing in divisive policies that exceed even her grandest follies. The time for dancing would have been when we’d defeated her politically, but our moment of victory never really came, and my 1990 revellers in A Different Sky unwittingly acknowledge this:

When [Nelson] came to rest on Dad’s shoulders, he could now see the top of another man’s head and there was hardly any hair there at all, just two grey patches at the sides. The man was walking past Dad and Will but he stopped for a moment, and his stiff grey suit made their denims seem even more soft and crumpled.

‘Great day, isn’t it, lads?’ the man said.

Will adjusted his voice to register his upbringing rather than his residence. ‘Absolutely, sir. Ding-dong, the witch is dead – now if we can just find a way to get rid of Bush and get out of the Gulf, we’ll be sorted.’

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Blessed not only with the hindsight with which I was writing but also the ongoing, austere repercussions of the banking crisis, those wearing party hats to next Wednesday’s funeral will know that the song they’re singing is really the elongated whinge of the defeated. We know that, if this is a political argument, it’s one that has played itself out. For her political opponents, the rap sheet against Thatcher was long throughout her time in office and, thanks to the 30-year rule on the release of Cabinet papers, the next few years could see it lengthen. We also know that she became a lightning rod for some historical and technological shifts that would doubtless have rolled by in any case; that, as Ian McEwan acknowledged in The Guardian, “there was often a taint of unexamined sexism” in the willingness to characterise her as a grotesque; and that dislike of her policies and personality morphed into a perverse fascination and a creative energy. We can look back on the Thatcher era with calm, rational minds, accept that she engaged with ideology, measure her power in terms of progress and damage; but the emotions her politics inspired remain in unbridgeable encampments.

Interviewed on the BBC website about his 2004 novel of the 1984-5 miners’ strike, GB84, David Peace commented on the impact of Thatcher’s confrontation with Arthus Scargill’s National Union of Mineworkers, whom she claimed represented “the enemy within, which is much more difficult to fight [than the Argentinian “enemy without”, defeated in the Falklands War] and more dangerous to liberty.”:

It wasn’t the strike that changed lives and communities, it was the government policy and the forces they brought to bear upon pits and communities in order to close pits that changed lives. I think it’s hard for people in 2004, especially younger people, to understand the levels of sacrifice that people underwent in mining communities during 1984/85; the loss of, on average, 9000 pounds per miner, 11,000 arrested, 7000 injured, two men dead – that men and their families did this in order to defend not only their own jobs and communities, but also those of other men in other pits and communities. Those pits and communities are gone, organised labour is gone, socialism is gone and with it the heritage and culture that held people and places together. That government and their policies changed everybody’s lives, not only the ones that had the courage to at least stand and fight.

GB84 is a brilliant piece of writing and an exceptional work of multi-layered storytelling. Reading it was also one of the most unpleasant experiences I’ve had with any work of literature, so effective was it in pitching me right back into the moment of the miners’ strike, the high point of defiance against Thatcherism and the decisive factor, as Peace says, in bringing to an end the influence of organised labour in British political life. Hate was thick in the air supply then. In a suburban South London sixth form, nowhere near the war zones of what were still considered mining communities, I experienced feelings of solidarity and venomous hostility towards classmates based on their relative views on the strike. It was a daily consideration for over a year, the country felt like an emotional furnace, and it was nasty. Reading Peace’s novel, it was a shock to be reminded of how much hate had governed everyday life, but in the midst of the Thatcher years, the strike was just the most full-throated expression of the hate that muttered through the 80s.

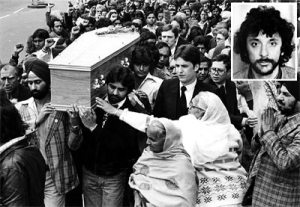

I don’t think it was Maggie Thatcher who taught me how to hate. For a non-white kid in a British city in the years after Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech, politicisation came early. The occasional insult in the street didn’t hurt much but it alerted me to racism, gave me – by way of the National Front – a focus for my nascent fear and loathing, and directed me (following my big brother’s tastes) to a mainly musical kindergarten for our political education. The Tom Robinson Band were stalwarts of the Rock Against Racism movement and were magisterially right-on, pushing anti-racism alongside feminism, unionism, opposition to police brutality and gay liberation. The anti-authoritarianism of Punk packaged hate in a discordant rage and cynicism that would have suited Thatcherism but related to the grey overture of the Wilson/Callaghan Labour years: entrenchment in the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’, the strident pomp of the Queen’s Silver Jubilee and the Winter of Discontent, along with the rise of the NF. As formative to a clenched-fist political identity as The Clash were, though, nothing would give vague left-leaning beliefs such focus and purpose as Thatcher’s response to the death of Blair Peach.

In the weeks before the 1979 General Election, in which the National Front fielded over 300 candidates, the Party staged a campaign march through Southall, one of the areas of London most synonymous with immigrant settlement. Peach was a white New Zealander, working in London as a teacher, and part of the anti-racist counter-protest which clashed with riot police. Though it took 30 years for the Metropolitan Police to issue even this basic acceptance of claims made at the time, Peach was beaten to death with a blow to the head from a police officer. I was approaching 12 when this happened. I was not world weary. I had not seen it all. I was shocked and chilled that racism had got so bad that they were now killing white people to protect it. And then Mrs Thatcher, campaigning to be Prime Minister, offered her understanding of the situation:

“People rather fear being swamped by an alien culture.”

The man was dead and her compassion was for the racists who decided I didn’t belong in the only country I’d ever known. Ten days after Blair Peach’s head was caved in, Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister. She’d give me plenty of reasons to stoke that hatred over the years but it was there from Day One for me, and for millions of others who refuse to be hypocrites by joining in the steel toe-capped hagiography in progress, and the millions who promised themselves they’d live to see this day but didn’t make it. It’s political, but it’s always been personal.

I can testify that Thatcher was an immense influence on the reasons I had to write, on the things I chose to write about, on the decisions I made about what I wanted from my writing life and very likely the things I wouldn’t do in the interests of a writing career. But hating Maggie Thatcher isn’t a sustainable creative impulse. She did, though, make me take care to choose my words. So I won’t waste next Wednesday mourning her passing. If there’s a glass to be raised, I’ll raise it to Blair Peach.